Chris Rock's zettelkasten output process

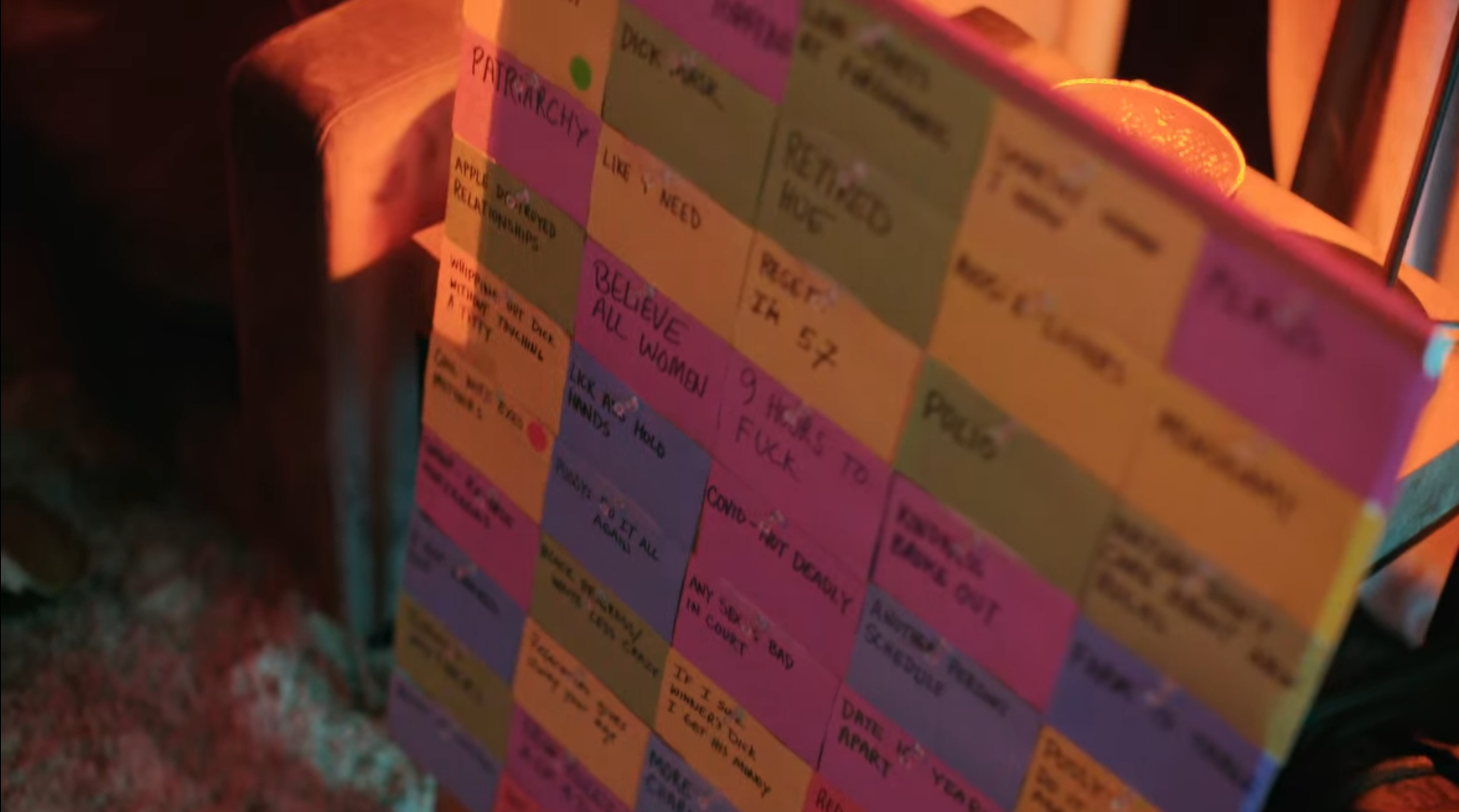

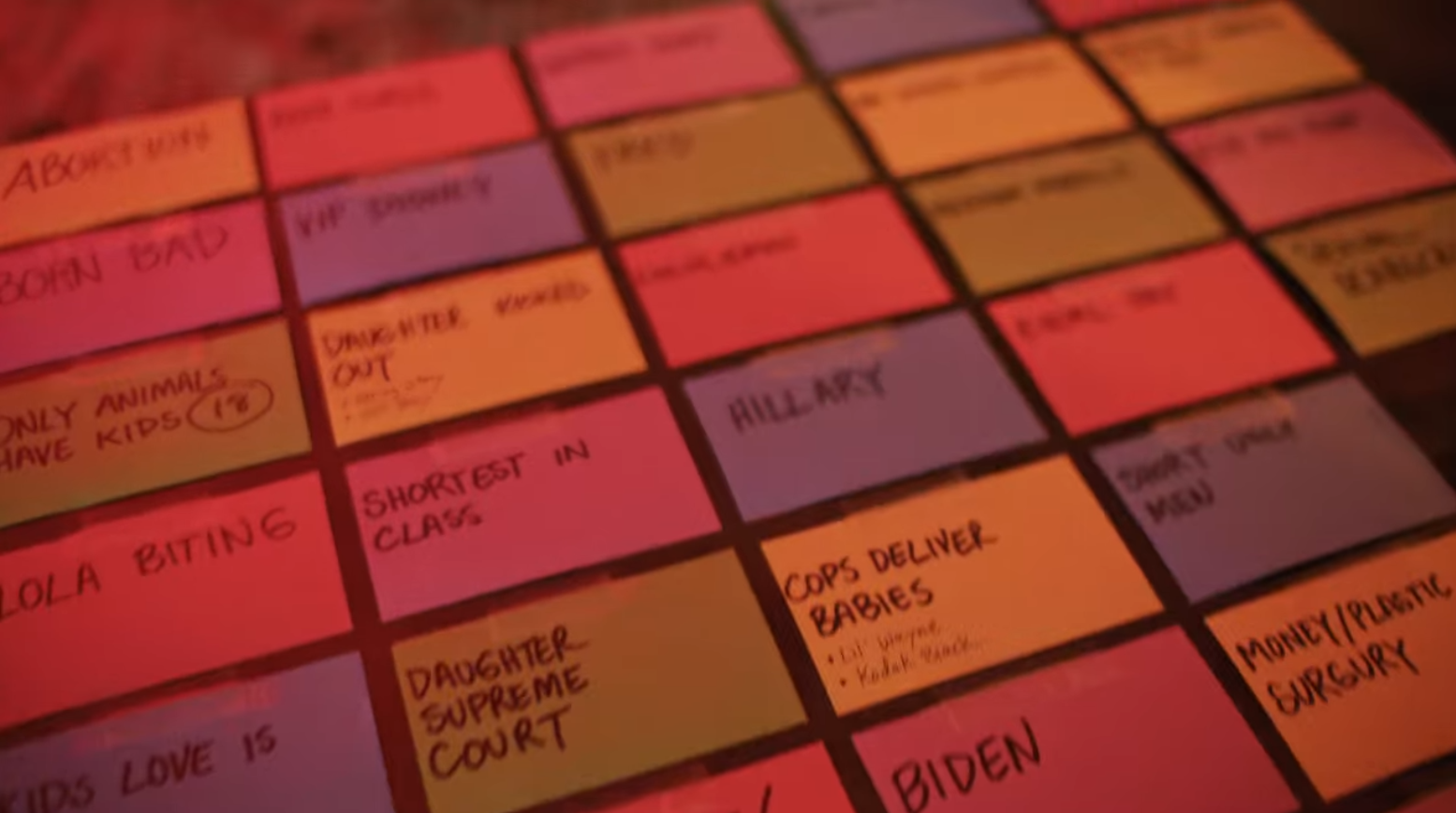

In the documentary Kevin Hart & Chris Rock: Headliners Only (Netflix, 2023) while preparing for a portion of their tour, Kevin Hart admires a portion of Chris Rock's stand up comedy method and calls it "a science". Chris Rock writes headlines for his jokes on slips of paper and then arranges them on either tables or small bulletin boards to outline his set list for presenting jokes for his performances.

If there are interesting contemporaneous news items which appear, he'll include a newspaper or other material to represent the related joke for inclusion into his set. This makes a fascinating means of outlining his material and seems to fall within the realm of my search for zettelkasten output processes. Even if Rock doesn't use index cards to write or store his jokes like comedians in the past have, he's using a slip-based method for outlining and arranging them as part of his output process.

Kevin Hart: Chris, I'm so... I'm so, uh blown away by what I'm discovering that is your process.

Chris Rock: My process.

Kevin Hart: This all your shit?

Chris Rock: Well, this here would be, uh, bullet points for tonight. Every card represents a joke or a reference that I choose. I don't wanna forget. You know what I mean? Like, you can remember all your jokes, but some nights, I'm like, 'ehhh, I'm not gonna close with this one. I'm gonna close with that one'.

Kevin Hart: You have it down to a science where you can bullet point the time.

Chris Rock: You can. And by the way, sometimes, something happens in the news.

Kevin Hart: You got jokes on the bench.

Chris Rock: I have jokes on the bench.

Kevin Hart: I'm going to tell you I'm not only impressed by that, but I'm disappointed in myself. Because, uh, whatever I got, got to to fly.

(Original post can be found at: https://boffosocko.com/2023/12/27/chris-rocks-zettelkasten-output-process/)

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

No piece of information is superior to any other. Power lies in having them all on file and then finding the connections. There are always connections; you have only to want to find them. —Umberto Eco

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

Shouldn't the title be "Chris Rock's Zettel output process" instead of "Chris Rock's Zettelkasten output process"?

Wo ist der Kasten? (Where's the box?)

I can see @Sascha shaking his head: "Das ist kein Zettelkasten."

I've got no evidence for nor against the presence of a box for these or any idea what the earlier portion of his process looks like at present. The bulletin board slips pictured were held up with pins and those on the table appear to be taped down, ostensibly to prevent accidental movement. Given their temporary nature and placement in this context, and the fact that they were highly portable for at least the span of the five shows he was preparing for in the documentary, there was certainly some container (even if it was as simple as a binder clip or a simple rubber band). Having seen shows like this roll in and out of venues before, I'm reasonably sure it was in a box at some point, so only a pedant would worry about it.

Box aside, the point here is that it shows a version of how he manufactures his output and manages his arrangement—portions of an overall process which are less frequently discussed and incredibly rarely visualized or pictured within the general community, much less in mass popular culture.

Many have argued that Eminem didn't have a zettelkasten either, and he definitely had both slips and a box. There's obviously no winning here... I won't worry too much about it until the naysayers' own Zettelkasten can manage to help them sell out Jones Beach Theater, The Prudential Center, PNC Bank Arts Center, Barclays Center, and Madison Square Garden.

Caveat pedanticus: Anyone talking about "Chris Rock's box" in public, might be held up to ridicule in his next sold-out tour. After Headliners Only and the Will Smith incident, I'm not taking any chances. 😜🃏🗃️

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

By Kasten I meant not only a physical box but also (although I wouldn't expect you to read my mind and intuit this implication) the metaphorical box of an organized storage system as used by scholars and such, whether analog or digital.

Cards temporarily affixed to walls are frequently used by facilitators of group meetings in business as well. That usage is not a Zettelkasten. It's just another usage of cards or Zettels. They have many uses beyond Zettelkästen. (I'm not implying that your post is irrelevant to this forum. It's certainly an adjacent usage of cards that can start an interesting discussion.)

You are seeing correctly.

To assume, that Eminem had a Zettelkasten because he had slips and a box is the same assuming that people are just sacks full of meat. The mere presence of parts is not enough to assume that there is a whole.

You can borrow the terms from linguistics: You need cohesion for the formal wholeness of your Zettelkasten (links, separate notes, etc.) and to have a good Zettelkasten, you need coherence (the actual connections between ideas). Eminem's box has neither cohesion nor coherence. It is almost the perfect example of what a Zettelkasten is not in the presence of its parts.

I am a Zettler

Chris is going to keep insisting that any set of slips is a Zettelkasten, and Sascha is going to keep insisting that a Zettelkasten is a cohesive and coherent system.

While I support anyone's freedom to stretch the definition of Zettelkasten as far as they like, I'm more sympathetic to Sascha's emphasis. I've been using sets of cards for various purposes from a young age, but a special magic started to happen when I started thinking of my notes as a cohesive and coherent cumulative system, and it's helpful to have a term for that.

I'm partial to the term personal knowledge base (or something like that) to refer to a cumulative organized storage system, as opposed to more transient facilitation techniques like Chris Rock brainstorming a set list with colored slips and a Sharpie marker. It amuses me that different people use the same term, Zettelkasten, to refer to both.

I will admit, though, compared to Chris Rock, Eminem is starting to look more like Luhmann. I guess it's all relative.

I never thought I would say "Eminem is starting to look more like Luhmann" on the Zettelkasten Forum. 😜

This could be the most incisive and penetrating assessment of Luhmann's contribution to sociology.

However, I like Luhmann's claims that society functions as an impersonal biological phenomenon, that the theory of mind plays no role in sociology, meaning that the systems that sociology studies cannot be understood in terms of the intentions of individual actors, and that the subject has been anthropomorphized. For Luhmann, sociology becomes a scientific enterprise when we think of groups, institutions, and nations, as zombie-like entities. I'm reminded of Alex Rosenberg's bracing physicalism.

GitHub. Erdős #2. CC BY-SA 4.0. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein.

From a marketing standpoint, I feel that I personally benefit from the inclusion of any incidence of slip based working under the umbrella of Zettelkasten.

The problem I see is that it hinders the collective understanding of what the actual idea behind the Zettelkasten Method is.

To give you an example: I had a female client, who wanted to lose weight. After some failed tries, I dug deeper, and it happened that she failed to organise time with her husband. She claimed that her family didn't respect her need for time, but in reality it was her who bent over backwards and violating agreements. The result was that she resented herself for being undisciplined, resented her husband for not being supportive and resented her body for being stubborn against her feeling what body she "actually deserved". Just providing her with plans (nutrition, training etc.) would've just resulted in her hardening her damaging and wrongly justified beliefs.

It is actually in the majority of cases that problems in health and fitness need to be solved on this deeper layer. (Though, my sample group is surely biased, since people contact a trainer only if they can't solve their problems themselves)

The Zettelkasten Method suffers from a similar problem: The vast majority of people assume that their challenge in dealing with knowledge can be met with systems and workflows (BASB, ZKM, GTD, etc.). But in reality, many lack the foundation necessary to solve basic problems of knowledge base (really like the term @Andy ).

(There is a prepared article on the deeper layer of the Zettelkasten Method already written and just needs editing and translation)

This why many people read articles, watched all the videos on YouTube, read Ahrens's book and simultaneously follow the method and feel lost. Isn't it strange that the method is actually pretty simple, yet still seemed to be so elusive and hard to learn?

So, while I benefit from the inclusion of almost anything under the Zettelkasten umbrella, I think it is clouding the collective thinking.

I hope this clarifies my pushback.

I am a Zettler

@Sascha said:

This is great. I can't wait to read the article on the "deeper layer" of ZKM. There is a term you probably know, depth therapy, that refers to psychotherapies that try to understand and change people's implict or unconscious meanings/beliefs instead of merely doing some superficial symptom reduction or behavior modification techniques (although for some problems the latter techniques are sufficient).

I consider GTD, for example, to be a brilliant workflow system, but it is completely lacking in "depth" in the sense just described because it neither emphasizes nor provides methods for questioning implicit, taken-for-granted systems of meanings/beliefs (or even unnoticed patterns in the environment). The part of GTD that is closest to "depth" is where it emphasizes reflection on higher-level goals and visions, but that is not the same as discovering and questioning implicit meanings/beliefs and building better ones. And there is usually no reason why GTD should emphasize depth, because deep inquiry usually does not "get things done" in business. But there are some problems that can't be solved (or even understood) without a method for deep inquiry and knowledge restructuring.

There is, in fact, a brand of depth therapy that has a name that is very relevant to the kind of cohesive and coherent system that @Sascha talked about above: it's called coherence therapy. A Zettelkasten Method can be a kind of coherence therapy for our personal knowledge base.

I am also looking forward to this. My approach starts with a re-evaluation of values. I take the maxim of Sönke Ahrens to make writing the only thing that counts literally (pun intended). I take notebooks everywhere and open Zotero and Zettlr on the computer before other applications. It's a privileged attitude--not everyone is so situated. For a long time, I was preoccupied with earning a living. But the single-mindedness of the artist and writer was a formative value: I grew up with artists and writers. My mother abdicated motherhood, she said, so she could lock herself in her bedroom during the day to write.

GitHub. Erdős #2. CC BY-SA 4.0. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein.

@ZettelDistraction said:

Same here. Before I had a smartphone, I carried a notebook everywhere since high school. If I still had the volume of thoughts I had when I was younger, I would still need a notebook (or cards, but I was always a mini-notebook guy, which I may have picked up as a student journalist in high school), but the brain is not squeezing out as many thoughts these days, so a smartphone usually suffices. Today I could barely think without my note system and reference manager.

Even Chris Rock needs his slips and Sharpie, even if it's just a few words per slip, and even if he throws them all away after the tour is over.

It might be a different situation for me. But I do the exact opposite. Whenever possible, I like my time with no pencil in my hand and no keyboard below them.

My current morning routine entails ~90 minutes of just doing stuff with no further input (ice bath, jogging, strength or mobility training). Also, when I walk my dog, I rarely take note. Sometimes, I do a voice recording.

I sit in front of my computer the majority of my waking hours. Therefore, the norm is to always be able to jot down notes. I value the time in which I just am left alone with my thoughts.

I am a Zettler

@Sascha said:

In my earlier years, my notebooks were always small enough to fit in a pocket, and now I have a small smartphone that fits in a pocket too, so I did not have a writing device in my hand at all times, to be clear.

I don't mean that literally. Many times, I don't even use my voice recorder because it is an interruption of my thinking. For that 90 minutes in the morning and the time in noon, I commit the heresy of just trusting that the important ideas will stick.

Other than these times, I don't have time for just being in the moment.

I am a Zettler

I’m waiting with excitement for this one! 😊

I'll agree with Wells that most of our difference here is nitpicking for the sake of argument itself rather than actual meaning.

Because we're in a holiday season, I'll use our holiday traditions to analogize why I view things more broadly and prefer the phrase "zettelkasten traditions". Much of Western society uses the catch-all phrase "Happy Holidays" to subsume a variety of specific holidays encompassing Christmas, Hannukah, New Years, Kwanzaa, and some even the comedically invented holiday of Festivus ("for the rest of us"). Each of these is distinct in its meaning and means of celebration, but each also represents a wide swath of ideas and means of celebration. Taking Christmas as an example: Some celebrate it in a religious framing as the birth of Christ (though, in fact, there is no solid historical attestation for the day of his birth). Some celebrate it as an admixture of Christianity and pagan mid-winter festivities which include trees, holly, mistletoe, lights, a character named Santa Claus, and even elves and reindeer which wholly have nothing to do with Jesus. Some give gifts and some don't. Some put up displays of animals and mangers while others decorate with items from a 2003 New Line Cinema film starring Will Farrell. Some sing about a reindeer with a red nose created in 1939 as an inexpensive advertising vehicle in a coloring book. Almost everyone differs wildly in both the why and how they choose to celebrate this one particular holiday. The majority choose not to question it, though some absolutists feel that the Jesus-only perspective is what defines Christmas.

I have only touched on the other holidays, each of which has its own distribution of ideas, beliefs, and means of celebration. And all of these we wrap up in an even broader phrase as "Happy Holidays" to inclusively capture them all. Collectively we all recognize what comprises them and defines them, generally focusing on what makes them mean something to us individually. Less frequently do we focus in on what broadly defines them in aggregate because the distribution of definitions is so spectacularly broad. Culturally trying to create one and only one definition is a losing proposition, so why bother beyond attributing the broader societal definitions, which assuredly will change and shift over time. (There was certainly a time during which Christmas was celebrated without any trees or carols, and a time after which there was.)

Zettelkasten traditions have a similar very broad set of definitions and practices, both before Herr Luhmann and after. Assuredly they will continue to evolve. One can insist their own personal definition is the "true one", while others are sure to insist against it. Spending even a few moments reading almost anything about zettelkasten, one is sure to encounter half a dozen versions. I quite often see people (especially in the Obsidian space) say that they are keeping a zettelkasten, when on a grander scheme of distributions in the knowledge management space, what they're practicing is far closer to a digital commonplace book than something Luhmann would recognize as something built on his own model, which itself was built on a card index version of a commonplace book, though in his case, one which prescribed a lot of menial duplication by hand. The idiosyncratic nature of the varieties of software and means of making a zettelkasten is perforce going to make a broad definition of what it is. Neither Marshall Mathers nor Chris Rock are prone to call their practices zettelkasten—primarily because they speak English—but they would both very likely recognize the method as a close variation to what they've been doing all along.

Humankind has had various instantiations of sense making, knowledge keeping, and transmission over the millennia classified under variations of names from talking rocks, menhir, songlines, Tjukurpa, standing stones, massebah, henges, ars memoria, commonplaces, florilegia, commonplace books, card indexes, wikis, zettelkasten and surely thousands of other names. While they may shift about in their methods of storage, means of operation, and the amount of work both put into them as well as value taken out, they're part of a broader tradition of human sense making, learning, memory, and creation that brings us to today.

Perhaps it's worth closing with a sententia from Terence's (161 BC), comedy Phormio (line 454)?

Translation: "There are as many opinions as there are people who hold them: each has his own correct way." Given the limitations of the Latin and the related meanings of sententiae, one could almost be forgiven for translating it as "zettelkasten"... Perhaps we should consult the zettelkasten that is represented by the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae?

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

I guess we need to collectively decide what the default meaning of "Zettelkasten" is. Given that Luhmann's version, and its digital variants are popular now, I would vote that the use of Zettelkasten therefore means the Luhmann version- as that is what most people are referring to at this point.

Which begs the question: What are the sine qua non features of a Luhmannian Zettelkasten and related workflow? What features from his analog workflow and systematic numbering and linking and indexing must be present in hybrid or digital instantiations to qualify as a "Luhmannian Zettelkasten"?

@JasperMcFly I'll presume that given the time differential, you may have missed my post just before yours which touches on the frivolity of the proposition of creating a single definition?

Most on this forum are going to presume that zettelkasten is precisely a slipbox in a similar form to that of Luhmann, but in practice some here and many elsewhere aren't going to see the distinction (or care). Some will unpopularly insist that a zettelkasten cannot be digital in form, but they'll also do so while simultaneously (heterodoxically and confusingly?) suggesting that one should use Wikipedia's Academic Outline of Disciplines, an idea which didn't exist during Luhmann's life.

You can make an attempt to force a definition, but I guarantee that it's a losing proposition as in practice people are going to use the word in almost any way they want—whatever you do, don't trust Humpty Dumpty's definition. It's the difference between prescriptive and proscriptive definitions. It can be seen in your very question if you look closely at your own phrase "beg the question", which in classic rhetoric means something very specific going back centuries, but in common use it has a dramatically different meaning. As ever, context will always be the king on these questions of definition, though some of us are still converging on a happy commonality.

For a bit more history here, try The Two Definitions of Zettelkasten.

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

Thank you and sorry @chrisaldrich. I did gloss over your wonderful post and missed your point about the losing proposition that would be ~ trying to create a single definition to broadly define them in the aggregate.

But, to rephrase my concern, I am not really interested in creating a set of broadly shared or minimum required characteristics by which to define a Zettelkasten in general, rather I would be interested in coming to agreement on what the essential characteristics of the specific Luhmann Zettelkasten are in particular. Then, would be able to compare those essential criteria against other kasten both analog and digital to discern the differences and deficiencies.

@JasperMcFly said:

I would say this issue has been pretty well covered here at zettelkasten.de (search the forum and blog) and elsewhere. Chris's blog post "The Two Definitions of Zettelkasten" that he linked at the end of his last comment would be helpful to read if you haven't read it. In the section "The rise of the new Zettelkasten" in that post, Chris mentions Manfred Kuehn, and I think Kuehn's 2007 essay "Some idiosyncratic reflections on note-taking in general and ConnectedText in particular" is still a good, though opinionated, take on this issue: "Lest anyone think that I completely endorse the description of the card index and its function, given by Luhmann, I should perhaps point out that I think it has fundamental problems..."

Here's the start of Kuehn's description of the key difference of Luhmann's Zettelkasten from its predecessors:

"Nothing to do with any systematic consideration of order or classification"—wait, IS KUEHN TALKING ABOUT EMINEM?!?

Kuehn noted that his thinking wasn't influenced by Luhmann's method until about 1999, despite the fact that Kuehn himself was a German-born scholar who had used an index card file decades before that time. As a user of both cards and various software systems, both before and after being influenced by Luhmann's method, Kuehn was well positioned to compare their characteristics in 2007.

By the way, the Niklas Luhmann Archive is at Bielefeld University, and, if I'm not mistaken, the proprietors of this website are citizens of Bielefeld (but are they really??) and graduates of Bielefeld University, so there is a close geographical connection between zettelkasten.de and studies of Luhmann's Zettelkasten. That may partly explain the prominence of Luhmann on this website.

@chrisaldrich said:

My first comment above that somewhat set the tone for what followed was nitpicking for the sake of LOLZ.

@Andy said:

Another thought: As much as I enjoy the LOLZ, and as much as I am moved to a state of peaceful oneness by Chris's heart-stirring invocation of a universalism of human sense-making, nevertheless I think there is a difference here that is not about what Wells called "misrepresenting one another" or about securing "the gratification of an argumentative victory". I see the difference as equivalent to the spectrum between democratic inclusiveness, on one end, and epistemic precision and systematicity, on the other end, as I described in several comments on a discussion of Adler's Syntopicon. To some degree, it's a spectrum of formalization. More generally, it's a spectrum of systematization. In fields like entertainment, systematization is unimportant; in fields like the sciences and systematic philosophy, it can be very important. As I said in the discussion on Adler, both ends of the spectrum are valuable. Nevertheless, there is a real difference. The tension between the two is part of what made that discussion of Adler's Syntopicon interesting to me.

Thanks for the links @Andy!

This is highlights one of the main downsides of not engaging with the arguments broad forward by the others directly.

Assuming that I am rational and tell the truth, I don't nitpick for the sake of the argument. Especially, in the light of benefiting from a practice I feel is detrimental to communities ability to learn (1. Marketing Effects, 2. I benefit financially from the lack of understanding)

Or: The Zettelkasten community tries to understand Christmas. Yes, there are plenty of approaches, but there is a consensus that we all try to celebrate Christmas well. "Happy Holidays" is the equivalent of PKMS or thinking tools.

Yes, there are many note boxes and slips that are used as thinking tools or PKMS, yes as Zettlers we can engage, learn or sometimes tolerate the inferiority of Non-Zettelkasten-Knowledge-Bases without hubris. Still, Zettelkasten is Zettelkasten, more than a note box with slips of paper in it.

I am a Zettler

I've been working towards this goal for some time. The idea isn't simply delineating the characteristics of Luhmann's system and its comparison to others, but to discern what the broadest characteristics of all of these systems are and what sorts of affordances those pieces and forms provide as tools for organizing and thinking. This will allow a broader range of people with different needs and different abilities to pick and choose which characteristics and methods might work best for them to reach those particular goals. Too many are approaching zettelkasten with a surface level understanding and somehow hoping that it will magically solve all their problems. When it doesn't, "consequently," as Luhmann would say, "just like in porn movies, they leave disappointed." [ZK II note 9/8.3]

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

Like @Andy I'm here for the LULZ nearly as much as for the reasoned, pointed discussion, systematization, and the formalization. I'm just as happy to delve in deeply as the next serious person, but I also know that the broader public is only likely to see or understand the topic at a very surface level and far fewer are going to delve into the level of reading comment 19,293 on the infamous zettelkasten.de site. For those interested in the greater depth, let's look more closely at Sascha's argument.

The key questions at play here are where is the work of a keeping a zettelkasten done and how is represented? Where is the coherence held? Is the coherence even represented physically? Does it cohere in the box or elsewhere?

The desk in my office (and that of countless others') can appear to be a hodgepodge of stacks of paper and utter mess. Some might describe it as a disaster area and wonder how I manage to get any work done. However, if asked, I can pull out the exact book, article, paper, or other item required from any of the given piles. This is because internally, I can remember what all the piles represent and, within a reasonable margin of error, what is in each and almost exactly where it is at, or even if it's filed away in another room. Others, who have no experience with my internal system would be terrifyingly lost in a morass of paper. The system represented by my desk is an extension of my mind, but one which doesn't need to be directly labeled, classified, or indexed for it to operate properly in my life and various workflows. One could say that the loose categorization of piles is the lowest level of work I could put into the system for it to still be useful for me. However, to those on the outside, this work appears to be wholly missing as they don't have access to the information and experiences with it that are held only in my brain.

By direct analogy, I suspect that Eminem's zettelkasten, and that of many others, follows this same pattern. They neither require internal "cohesion nor coherence" in their systems which are direct extensions of their minds where that cohesion and coherence are stored. As far back as Andreas Stübel (1684), many (including Niklas Luhmann) have used variations of the idea "secondary memory" to describe their excerpting and note taking practices. [1][2] Many in the long tradition of ars excerpendi have created piles of slips which held immense value for them. So much so that they would account for them in their wills to give to others following their deaths. In many cases, these piles were wholly useless to their recipients because they were missing all of the context in which they were made and why. Lacking this context, they literally considered them scrap heaps and often unceremoniously disposed of them.

In the case of Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten, he spent the additional time and work to index and file his notes thereby making them more comprehensible and possibly of more direct use to people following his death. For his working style and needs, he surely benefited from this additional work, particularly when taken over the longer horizon of his zettelkasten's "life" compared to others'. However, it's not always the case that others will have those same needs. Some may only want or need to keep theirs for the length of their undergraduate or graduate school careers. Others may use them for short projects like articles or a single book. This doesn't mean that there isn't coherence, it may just be held in their memories for the length of time for which they need it. Those who have problems with longer term memory for things like this may be well-advised to follow Luhmann's example, particularly when they're working at problems for career-long spans.

In Eminem's case, given the shape and size of his collection, which includes various sizes, types, and colors of paper and even different pen colors, it may actually be easier for him to have a closer visual relationship with his notes in terms of finding and using them. ("Yes, that's the scrap I wrote for 8 Mile while I was at that hotel in Paris. Where is the blue envelope with the doggerel I wrote for my daughter?") It's also possible that for his creative needs, sifting through bits and pieces may spark additional creative work in addition to the slips of work he's already created. Cohesion and coherence may not exist in his notes for us as distant viewers of them, but this doesn't mean that they do not exist for him while using his box of notes.

As an even more complex example, we might look at the zettelkasten of S.D. Goitein. His has a form closer to that of the better known commonplacing practices of Robert Greene and Ryan Holiday. While Goitein had a collection of only 27,000 notes (roughly a third of Luhmann's), he had a significantly larger written output of books and articles than Luhmann. Additionally, Goitein's card index has been scanned and continues to circulate amongst scholars in his areas of expertise by means of physical copies rather than a digitized repository the way that Luhmann's has over the past decade. Despite Goitein's notes not having the same level of direct cohesion or coherence as Luhmann's, I suspect that far more researchers are actively and profitably using Goitein's collection today than are using Luhmann's.

For those who are more visually inclined, an additional example of the hidden work of cohesion and coherence can be seen in the example of Victor Margolin.

In this case, Margolin is certainly actively creating both cohesion and coherence. The question is where does it reside? Certainly, like many of us, some of it resides internally in his mind and in coordination with the extension of it represented in his note cards, but as he progresses in his work, much of it goes into his larger outlines drawn out on A2 paper, and ultimately accretes into the writing that appears in the final version of his book World History of Design.

As described in his video, Margolin doesn't appear to be utilizing his slips as lifelong tools for other potential projects, nor is he heavily indexing or categorizing them the way Luhmann and others have done. This doesn't make his zettelkasten any less valuable to him, it only changes where the representation of the work is located.

Naturally, for those with lifelong uses of and needs for a zettelkasten, it may make more sense for them to put the work into it in such a way that it appears more cohesive and coherent to external viewers as well as for their future selves, but the variety of methods in the broader tradition, make it fairly simple for individual users to pick and choose where they'd personally like to store representations of their work. If you're like philosopher Gilles Deleuze[3] who said in L’Abécédaire

then perhaps you may wish to have better notes with the work cohered directly to, in, and between your cards? Surely Deleuze didn't start completely from scratch each time because in reality, he had a lifetime's worth of experience and study to draw from, but he still had to start from what he could remember and begin writing, arguing, and working from there.

This is why having a lifelong zettelkasten practice is more productive for most: it acts as a knowledge ratchet to prevent having to start from scratch by staring at a blank piece of paper. The benefit is that—based on your personal abilities and preferences—you can start somewhere simple and build from there.

Finally, I'll mention that in Paper Machines, Markus Krajewski calls Joachim Jungius' the "first practitioner of nonhierarchical indexing". In talking about the idiosyncratic nature of Jungius' zettelkasten for which "There are no aids for access, no apparatus; neither signatures nor a numbering of the cards, neither registers nor indexes, let alone referential systems that guide one to the building blocks of knowledge." he says[4]:

If this is the case, then Marshall Mathers is surely channeling Jungius' practices, as I suspect that many are.

Perhaps in The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare may have just as profitably written:

References

(A portion of this post appears originally at https://boffosocko.com/2024/01/11/on-cohesion-and-coherence-of-the-zettelkasten-where-does-the-work-reside/)

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

Thanks so much for your great previous comment and related blog post, @chrisaldrich!

If you haven't already studied it, you may want to read a report that I mentioned in a previous discussion of what we jokingly called ZK® (the LOLZ never stop...): Stephen Davies, Javier Velez-Morales, & Roger King (2005), "Building the memex sixty years later: trends and directions in personal knowledge bases", Department of Computer Science, University of Colorado at Boulder. It's a survey of digital personal knowledge base software circa 2005 that I suspect would provide good ideas for a project like what you described. (By the way, I would like to see more emphasis on analysis of data models as found in Davies et al., which, it seems to me, has been greatly underemphasized so far in ZK® discourse and in your own writings that I've read.) The scope of their report just needs to be expanded to analog systems, extended backward as far as desired and forward to the present day, and perhaps embellished with a little of your cognitive anthropology.

These questions have very simple answers. In Luhmann's personal Zettelkasten coherence achieved by creating a system. System has a very specific meaning, since it was Luhmann's own concept of system. It was physically represented by the fixed order ("feste Stellordnung") which was grown by a set of rules that were (together) sufficient to create a Zettelkasten.

I guess I can't get my point across.

I am a Zettler