The Principle of Atomicity – On the Difference Between a Principle and Its Implementation • Zettelka

The Principle of Atomicity – On the Difference Between a Principle and Its Implementation • Zettelkasten Method

The Principle of Atomicity – On the Difference Between a Principle and Its Implementation • Zettelkasten Method

The deepest dive into the principle of atomicity on the whole internet.

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

What an absolutely fantastic post. In a coincidence, I had, for the first time, finished Bob Doto’s book yesterday. One of the notes that I took was:

The reason we’re able to relate ideas within different trains of thought is due, in part, to atomization, the practice of reducing ideas to their essential points.49 Atomicity makes ideas highly sensitive to context. The more “atomic” an idea, the more broadly you can employ it. The more complex an idea, the less surface area it has to be connected to others. ([Location 877]

- Note: I wonder if the right way to go is bottoms up (the pure zettlekasten way) where we have atomic notes that evolve into bigger threads or bottoms down, where a thread is developed and atomicy is a byproduct of the threads increasing complexity. Perhaps this is analogous to Milo’s architect/gardner concept. Does it relate to structure must be earned? If so, in which direction?

I originally used Obsidian when it first came out merely as a reference material store for my projects in OmniFocus. Then I recognized it could be the repository for the higher horizons of focus in the GTD methodology, which I had been unsatisfied with managing for decades. The “area of focus” pages that I created prompted me to add what I called “objectives” for each area as headings in the note. This led to a creative process of thinking about how I might guide myself to achieving the objective. The pages became long and complex, so the objectives became their own notes as soon as they had any heft to them and the musings about how I would achieve the objective evolved organically to became projects or reference material for projects and themselves turned into their own notes. This was a primitive bottoms up atomicy example.

Next, I recognized that the linked note metaphor was particularly valuable in my advisory work with CEOs (I sit on the board of directors of several tech companies). When I would be asked a question, I would create a note. Many questions were related which required me to rework the answer into more atomic units. It became clear atomicy was a desired outcome of this part of my linked notes system. As this became more mature, and I had more and more valuable atomic notes, I found that instead of answering a question, I would look for notes on similar topics and would compose them into an answer. The quality of the answers was significantly higher as the notes and the process of “colliding” them (hat tip Nick Milo), produced deeper insight.

As I perfected my thinking system, I discovered zettlekasten and realized there were people thinking deeply about the problem. Everyone seemed to be an academic focused on surviving the publish or perish environment, but my value was derived from linked notes as a thinking environment to improve the quality and accuracy of my understanding of my field.

I love that you are explicitly calling thinking out as a primary use case at the same level as writing. I also love that you are aligned on integrated the thinking process into the zettlekasten. The “idea emergence” diagram that Nick Milo created to describes this process (any version of this: https://x.com/nickmilo/status/1556989944744366080?s=61&t=d4avUKZro_xB7MgJ_b3foA) has always resonated with me. I find that most of my atomic notes are created not from scratch but from “breaking off” from a more complex thought(note).

Very good post, @Sascha! It's a good synthesis of various issues related to atomicity, pointing to how atomicity can contribute to the systematization and systematicity of our knowledge work.

@Sascha said:

I don't doubt that our hosts at zettelkasten.de deserve credit for popularizing the term "atomicity", and Sascha certainly should be expected to emphasize that. I would add, however, that in the academic research literature on hypertext and personal knowledge bases, the same principle is called "granularity" since the 1980s. For example, here are a couple of publications that I've mentioned elsewhere in the forum (here and here and here):

And, for example, here are a couple of earlier publications from the 1980s (the second one is about IBIS, which I've mentioned often, and other publications by Jeff Conklin from the same period discuss granularity, which is important to any discourse schema like IBIS):

@Sascha said:

Again, this can be found in the academic research literature such as the publications mentioned above, among which Völkel (2010) has a particularly rigorous definition.

Just like Sascha and his knowledge building blocks, people who have written well about such knowledge elements usually draw from existing knowledge in fields like analytic philosophy and argumentation theory. (I'm reminded of Dorian Taylor's joke in "The symbol management problem": "A side effect of spending too much time working with the Semantic Web proper is analytic philosophy.")

@ehuddleston said:

@ehuddleston's first paragraph here is also a major way that I use my note system: as a way of doing what David Allen (GTD creator) called self-management. And I think the second paragraph here, about a workflow based on questions, again shows the similarity to IBIS, which I've mentioned often, where questions ("issues") are central elements.

@Sascha

Excellent article - thank you!

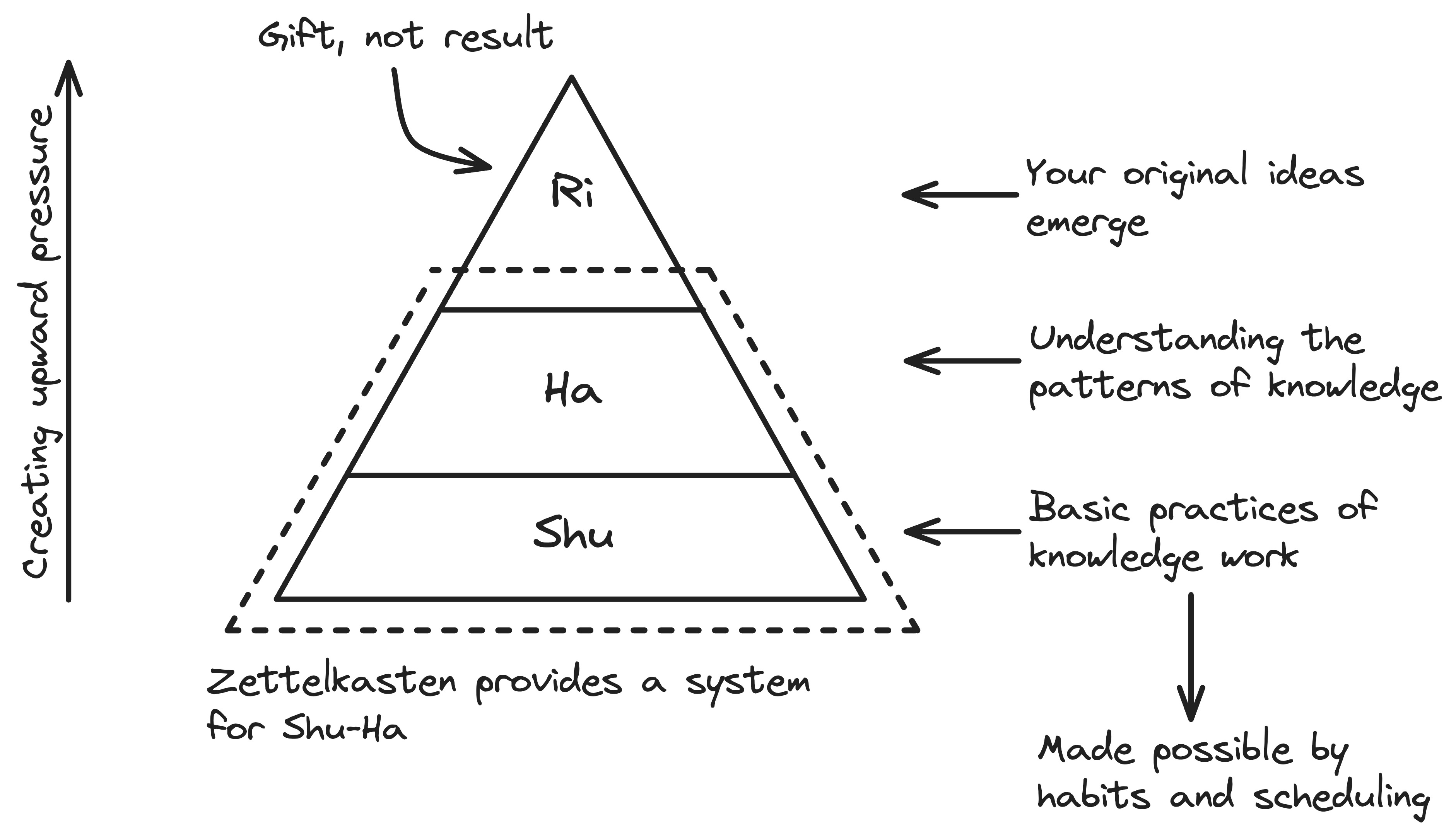

I like your Shu-Ha-Ri model as a way of explaining where a person might be in their understanding and practice of the Zettelkasten method. This of course applies to pretty much everything we learn in life. It reminds me of Obi-Wan Kenobi and Yoda trying to teach Luke Skywalker about the Force and how to use it

I agree with the idea that atomicity is something we strive for but can take a significant amount of time to achieve (depending on the subject of a zettel and our knowledge of it). Hence we need to be patient. I don't get too worried about when I've reached that point, although I do use various tags to indicate when I think a particular zettel is getting close.

Really good article :-)

Creative work doesn’t play by conventional rules · Author at eljardindegestalt.com

Thanks!

Sounds awesome! Based on what you are describing, it seem to me that you are pretty much following atomicity as a guiding principle, instead of a condition for the input.

And, dang: Nick Milo has some talent to make things sexy.

You could even go back to Plato's ἰδέα (idea) to trace back this .

But I think granuality is quite different from atomicity. Atomicity aims at a particular "stand-alone" characteristic. Granularity seem to be more relationial. Marshall (1987) seems to do the opposite: Instead of stating that there is something that you can arrive at, she seems to state that everything is a bottomless pit.

But you are pointing to a particular blindspot of mine: My thinking is insufficiently rooted in proximate fields represented in sources you mentioned. I will work on this vice.

Here, I have to push back. I am specifically talking about atoms in the context of note-taking and knowledge. Knowledge is not a linguistic structure. I think linguistic structures are tools to get into contact and, mh..., "capture" knowledge or contain knowledge.

For sure, there are concepts about small parts that constitute the bigger thing. But they are from different fields and stay in different fields.

(Looking forward to be burried in counter-examples...)

You take any chance to throw in a reference to IBIS.

I am a Zettler

@Andy Going through my second brain (I call it Rumen), I encountered a possible project called "Practical Ontology and Systems Theory". The entities I construct, though they are similar to knowledge building blocks, are not an equivalent. Entities are for example:

A justification could be (most likely is) part of the inventory for other classification systems of information, still I don't put them in the same category. I am something like a knowledge realist: I think knowledge is a real entity that you can understand and research, not a knowledge constructivist who would put knowledge in the realm of the mind.

Perhaps, the biggest difference between knowledge building blocks and the above-mentioned approaches is that the approaches are functional/linguistic. Oh, I repeated myself. But I let it in, since this is a major pillar for me.

I am a Zettler

Great article - I do think resources articulating the whole ZKM process are in early stages.

I am apprehensive introducing friends to the ZK because of friction like thinking notes need to be atomic before putting them in - the issue is widespread because resources out there mostly imply it (until this article). But still, pointing my friends to a load of articles is still a big barrier unless you're naturally into this sort of stuff.

Zettler

You have a (two) very solid point. I will address that!

I am a Zettler

Later Wittgenstein overturned his own argument and achieved even greater things

Very nice article!

Even before I started Zettelkasten, I was thinking about the concepts of "jori" (조리) and "galpi" (갈피). They're Korean.

Jori is a galpi that matches(connects) the front and back of words or things and is systematic.

(It is usually translated as logic or reason: Jori is the quality of words, a piece of writing, work, behavior, etc., making contextual sense and being logical.)

Galpi is the eoreum that distinguishes the parts of things.

(It is usally translated as space between layers, or border: Galpi is the perimeter of a certain thing that separates it from others.)

Eoreum is the space where the ends of two objects meet. (a very narrow gap)

So, based on the Korean words above, I learned that understanding starts with recognizing things as a whole, and then gradually distinguishes them in detail until they are indistinguishable. And this knowledge fits perfectly with the argument you presented!

When I started Zettelkasten and read your Introduction, I was fascinated by Atomicity as the input type, so I felt the same way as @Nori. (I felt like my thoughts were being torn apart.)

But after several years of Zettelkasten, I realized that breaking up notes into a single file felt more natural. Reading your article at that moment gave me a vague sense of certainty.

And after reading this article today, it became clearer. I'm glad my thinking has become clearer.

Thanks, Sascha!

@iylock

I wonder how it is to think in Korean, having these specific concepts available. I don't think that in German, there is a word that fits the meaning of 조리 good enough. My discussion with AI led me to "Stimmigkeit". It means something like "harmony, something fitting together".

But the difference seems to be, that jori is something that is between the individual words. Stimmigkeit refers to the whole.

At least, my feel is that the Korean concepts are hyper-precise.

I am a Zettler

Very very interesting.

I think I’ll spend quite a bit of time on your post, it hit me.

At the same time, I often find myself going in the opposite direction.

From entities that gradually emerge, I see relationships that suggest to me they could be part of something more general, and those entities become parts of a whole that emerges.

I see a bidirectional process.

Today I've read this page and collected a few thoughts on it.

I'll organize them and then write my post about.

Right now, I feel like saying this consideration.

I have many years of experience as a software developer and engineer.

I can say that in the context of object-oriented development, the equivalent concept of atomicity can be learned by reading three lines of text, but mastering this seemingly simple concept for the field practice takes years, and you only achieve it after producing tons of mediocre code :-)

It's a concept as simple to explain as it is complex to put into practice when you need to produce something truly valuable, going beyond initial toy examples.

I found the concept of atomicity "intuitive" because I've been banging my head against it for years writing code.

Despite this, in the context of the Zettelkasten, I've studied it again, from the start and in all its forms.

My "atomic" zettel has 40,000 characters and 121 links to other zettels that are distinct "frames" of the same concept.

Yes, my atomicity idea is far from atomic into my zettelkasten :-)

This article is probably the best response to the Great Folgezettel Debate yet. I like how @Sascha characterizes their work habits and goals in order to make a distinction I agree with: zettelkasten as a prompt machine vs. zettelkasten as a thinking machine. Understanding their approach in terms of what they are doing, or intending to do, is clarifying. I think missing the thinking machine aspect is where people too quickly get frustrated and abandon the method because of the false advertisement of it spitting out finished pieces left and right.

It's not just a memory aid, any note system could do that. It is a thinking aid.

I think you can use folgezettel to think so this doesn't officially close the debate per se, but this is maybe my favorite post on the subject and on the site in general. Great read.

I also appreciate the nuancing of the popular conception that "atomic" means "short." Is that how atoms work in science? I'm a historian so somebody tell me if that is the case.

Anyway, atomic in my experience can be complex, and I think this nuancing of the term is more consistent with multiple philosophical conceptions of the "idea." For my work, the idea is the effect of an event (virtual or actual) on a network of relations as it emerges. The most atomic expression of that idea is the description of an irreducible relation in that network. This can be short, but often (maybe ironically) it requires more work in writing to fully establish that particular relation's irreducibility in the zettelkasten. It's like a proof of the relation's irreducibility.

I wanted to write down quickly some of the reflections I had while reading the article, but then it exploded into a very long text...

I wrote it in Italian first to save time, and honestly I don’t feel like translating it into English now, so I’ll rely on ChatGPT. If there are issues in translation, its fault...

The idea that the Zettelkasten is based on principles, and that each principle can be implemented in different ways, is fundamental and it’s always worth repeating.

I believe it is the most important concept in your whole story. It’s the definitive answer to any form of fundamentalism regarding Zettelkasten.

Zettelkasten should be studied in terms of principles before techniques. (But even before principles, its purpose should be understood above all).

Regarding atomicity, I agree with the point that it should be considered first as a principle rather than as implementations.

Still, for my taste, it should be made explicit that, even though it is a principle, it is not mandatory in the Zettelkasten—at least not in every note, not even in the outcome-based approach. Perhaps this is implicit in the text, but I would have stated it clearly at the beginning.

If atomicity creates difficulties for me, at least initially, and in edge cases where it doesn’t produce satisfactory results, I simply totally bypass it.

My "Zettelkasten zettel" into my zettelkasten is far less than atomic, and never will be. But it works, so I don't care.

I find it is correct and useful to highlight the two modes, “by input” and “desired outcome,” but honestly I found the terms themselves a bit unclear.

As a IT guy, I might have coined them differently: the first maybe “Ahead Atomicity” or “Early Atomicity,” the second “Eventual Atomicity.”

In computer science, two similar expressions are used for the same phenomenon: "Strong consistency" and "Eventual consistency". The first denotes an “a priori” property, the second something that “reached over time”, eventually.

In a reflection I wrote months ago, I may have used “Just in time atomicity” or “Deferred atomicity” for the second case, but now that I think about it, I much prefer Eventual instead of Just in Time or deferred.

Of course, this is just a matter of naming, nothing particularly important.

Between the two approaches, from my perspective, I’ve practically always used the second one since the beginning. For me, ideas within the Zettelkasten have always been malleable and continuously subject to refactoring: over time, they may grow and then split.

In explaining this concept, I personally would have added two more dynamics, so in total there are four. The first two are already in the article, I'd explicited third and fourth:

ideas that enter atomic and remain atomic

ideas that enter non-atomic and will one day be atomized

ideas that enter atomic and simply remain as they are :-)

ideas that enter atomic but grow over time; I can then decide whether to split them or not

The system with maximum flexibility is the one that makes all these possibilities explicit. This model treats atomicity not only as eventual but also entirely optional, at least for some notes.

On the question of the Zettelkasten as a prompt machine:

Perhaps the term prompt is somewhat inappropriate, especially today when “prompt” almost exclusively means a request to an AI.

I really liked the definition you gave in the video with nori of "stimulus", I would have used that or, even better, "trigger". I feel my notes are often triggers for my mind.

Personally, I would have written that section in a more neutral tone. :-)

The way it comes across is that one way of doing Zettelkasten is “better” than the other. I would have simply written: “There are two ways,” pointing out the strengths and weaknesses of both.

I also wouldn’t have referred to Bob Doto’s work in that way, to be honest.

Presented like this, it suggests that the Prompt-Based Zettelkasten is inherently limited, and I disagree with that.

The Zettelkasten behaving like a Prompt Machine has its own particularities:

To me, the statement “For this writing process, you don’t need a Zettelkasten at all” is far too drastic. Too reductive.

I do agree with the idea that certain ways of doing Zettelkasten transfer more value to the Slip Box than others. I also believe that if I lost my slip box entirely, I would still retain what my brain has become after three years of practice.

However, this doesn’t necessarily represent an absolute value. It depends on the fact that, if the prompt-Zettelkasten is already optimal for my purposes, it might make no sense to change the system—risking worse results—just to make it “less indispensable” and gain something else I don’t even need. If I am a writer and my current system works perfectly for my job, that’s totally fine.

Now, something important for my interpretation of Zettelkasten.

Some time ago, I wrote that I see the** Zettelkasten as an author–slip box system**, not just as a slip box (the artifact alone).

From this perspective, I can make some evaluations.

Following this interpretation, I wouldn’t say that a prompt-based artifact is “worse” than one made of full-fledged ideas. What matters is whether the pair author–artifact works well.

If your text suggests that the prompt system is “a little less” of a Zettelkasten because the thinking happens outside the slip box, in my view it still qualifies as a Zettelkasten, because the thinking process remains within the author–slip box system, even if outside the slip box itself.

The slip box could not represent the whole thinking process behind the note, but this process happens, and the important thing is that what is represented is enough for my purposes.

Overall, I personally don’t think one can evaluate the quality of someone’s Zettelkasten practice “just by looking” at the slip box. The slip box is a by-product of the process.

What matters is not how I see someone else’s slip box, but how well that slip box works for its author.

For a telling example: I would personally consider Luhmann’s slip box a terrible slip box for me :-) but the point is—it wasn’t my Zettelkasten.

It’s true that the full-fledged ideas model allows for creating something like Luhmann’s system (a system with options is more general than one with constraints). Still, there might be advantages, not mentioned in the article, to starting directly with Luhmann’s approach in mind. And flexible system can have their own issues: it seems conterintuitive, but it is even better shown by the fact that many people prefer a very rigid system to a flexible one when they choose an analog zettelkastan instead of a digital one.

About this I'd like to hear the opinion of a prompt based Zettelkaster author.

Another important point for me:

The reduction of an idea into a statement doesn’t necessarily imply less thinking than a full-fledged idea.

In my specific case, quite often, to arrive at a short statement that “says it all” and to use it as the note’s title, I go through a significant mental exercise. A statement is shallow thinking only when I’ve just copied or loosely reformulated an idea from a source. But it can also be the maximum exercise in deep synthesis.

Of course, leaving only the statement and nothing else isn’t what I usually do: since I’m already doing the deep thinking, and I have it directly in the slip box—I leave it inside the note, why delete it? But if had an analog system, maybe could make sense having only the prompts.

And what’s underestimated is that even when we only have a statement, there’s also the network of connections that expresses and represents much of the author’s mental process. Connections carry meaning and are just as much a product of thinking as the content of individual notes.

I sometimes come across cases where what remains of value is an outline note made up of many note titles, and thus statements, which are sufficient to use without referring back to the body of the note, whose substance has by now largely “exhausted” its usefulness. What remains significant for practical use is the train of thought formed by the titles, not the support contained in the bodies. I don't always need the body of the note over time, even if it is present.

On the section about the six building blocks of knowledge:

I’m not entirely convinced they are exhaustive for expressing any kind of idea produced by any Zettelkasten practitioner (scientist, writer, poet, artist) in any context. Maybe they’re sufficient for academic research, but in general I’m not sure.

I haven’t reflected deeply on this, but it seems too narrow, too tied to logic and science. If I wanted to express sensations, impressions, subjectivity—things like that—should I be forced to do it in a “technical” way? Thinking, in its broadest sense, is a more extensive practice than reasoning alone.

Ultimately, true to the idea that Zettelkasten is an author–slip box system built on principles, for me the two approaches are on the same level.

There is the one that suits me best, not one that is objectively better.

Personally, I use a system that is actually somewhere in between the two.

Some zettels follow one canon, others follow another. I’ve noticed that in some situations I need prompts, while in others I need robustly developed ideas.

And, I often have both forms for the same idea: the prompt in the title and the development in the body :-)

@Sascha I have some opinions about how Korean thinks, but I'm not sure if they'll be useful to others, as they're heuristics or based on shallow processing (i.e., underdeveloped).

@andang76 I'm glad it helped you.

This is what I am trying to push. A writing tool doesn't need to do much, especially, when you already know what you want to write about. These super short notes that contain claims, strong aphorisms etc. work very well.

I think what you wrote below is the best description of writing about connections I encountered. You will be quoted!

I think Folgezettel don't harm. But I think they are so low on the hierarchy of value creation tools that they are a waste of time because of the opportunity cost. I used them for quite some time, both physically and digitally. They worked fine. But position is after all not important and shouldn't be important. And Folgezettel don't provide any elaborate link context. You can provide it within the note, but Folgezettel doesn't help with that.

So, I agree: It can be done with Folgezettel. But if the position is not important, why bother? The aesthetics can be nice.

I wouldn't go that far that it is actually a proof (if you disagree, I would be really curious to see such a proof! Perhaps, you are more meticulous than me), but as a metaphor this is gold.

I'd settle for a good explanation. OK... while writing this, "proof" is actually the best form of connection.

Way deeper than my knowledge. So, give it to me.

So, give it to me.

I am a Zettler

Okay, I'll get it ready soon

If it is a principle, it applies to the Zettelkasten and not to the note. A note that is not atomic is not atomic yet. It might never be, but never say never.

So, what if out of your 50k not a single one is atomic? You still applied the principle of atomicity if you moved towards it.

A principle is nothing to reach, but to strive for.

(Perhaps, I am posting this because of me thinking about my boxing teacher, who hit me quite a lot, as he did with everybody)

This is also what I often say during coaching (both for health/fitness and Zettelkasten): If it works, it works. Change is then more of a risk and less of a chance. (Doesn't mean that you never take the risk)

I think that comparison to code is pretty on point: If the code works, you don't need to bother about clean code, until you have to work with that code. The same is true for your note-taking and Zettelkasten. A stream of consciousnous put in physical notebooks can be precisely what you need and anything more would be overkill.

But if you want to actually develop a complex idea over a long period of time, you better have clean code and documentation.

What is the difference between 1 and 3?

I don't just referred to Bob's work that way, but to Cal Newport's, Ryan's and even Luhmann's.

>

If you like a prompt-Zettelkasten and the practice of it, this is fine. But the cost-to-benefit ratio doesn't add up.

I wrote "For this writing process, you don’t need a Zettelkasten at all." I am merely repeating Cal Newports critique of Zettelkasten, which applies here.

Most of the articles on this page are written completely without my Zettelkasten. I am in the same situation as Cal, Bob, Ryan and Niklas (first time I refered to the godfather by his first name -> I feel funny) in this particular domain: I know the material very well and am writing opinion pieces. I'd like to call them essays, since I don't just make claims, but provide arguments, at least when challenged. But nevertheless, a Zettelkaten is not needed for this writing process. This applies to me, too.

I wouldn't say that neither and completely follow your line of thinking (except including the author into the Zettelkasten).

The approach by these four fellas is much less powerful when it comes to using your Zettelkasten so think. And, obviously, that doesn't mean that the heavy lifting is not done anywhere. It just has to happen in the draft.

Thinking in your Zettelkasten is not a value in itself. My activity in community is me putting skin in the game for this statement. Almost all of my thinking about the Zettelkasten Method happens here.

Sure, and I agree. But I don't follow the value judgements that are attached to "a little less" and "still qualifies". I don't think in these categories, since I don't want to take part in a social game.

The problem that you create is that you'd basically erase the coding equivalent of documentation and testcode. The problems that arise from that are similar.

I don't make any claim that they are exhaustive. It is merely the case that I didn't needed to change the inventory for 12 years or so. And for fiction writers, I have a different inventory in which I have way less confidence.

Sensations and impressions are empirical observations, see my reply to @GeoEng51. But this is a meta-cognitive layer arround the practice. That doesn't have any implications on how you approach these thoughts unless you have scientific aim in mind. Perhaps, you reflect on the way how you create/retrieve such thoughts.

I am a Zettler

It depends on how it is formulated.

It could be

"Ideas into your Zettelkasten should..."

or

"All ideas need to... (now or later)".

I intend atomization principle in the first form. Present, but as an advice, not a rule.

there's a "not" missing here, I meant to say

" ideas that enter not atomic and simply remain as they are :--)"

I'm not convinced of this. I later reflected, for example, on why a simple outline process can't replace a zettelkasten prompt, as you called it. When you start having tens of thousands of pieces of text accumulated over the years, you start to need the zettelkasten's properties of scalability over time and space, antifragility, and findability provided by the network of the connections and emerged structure. If you don't organize those prompts as if they were a zettelkasten, you probably won't be able to use them effectively and might even lose them.

In this reasoning, we risk arriving at the paradox that Luhman's Zettelkasten, the zettelkasten par excellence... is not a zettelkasten or a less powerful zettelkasten :-)

There's something strange about this logical process.

So we need to start saying that the Zettelkasten is "that other thing over there," and it's you and I who are doing... something that isn't a zettelkasten :-)

My opinion remains that we have a Zettelkasten when the thinking process is made by the author with the support of his slip box, not only when the whole thinking process is expressed by the slip box on its own. Your requirement is too strict for me.

Ah, got you.

Uh, nobody is saying that XY is not a Zettelkasten. I don't follow.

I am a Zettler

If I put together all the considerations you made in the article and in the comments, it seems to me that you basically reached the judgment that a prompt-based system is not capable of producing results comparable to a fully-fledged representation system, if not even "not a zettelkasten"

It may be that it cannot provide exactly the same things a fully-fledged system offers, but that doesn’t necessarily mean all Zettelkasten practitioners are looking for those things, so there should be no evaluation in absolute terms.

For example, it might be very complicated to use a prompt-based Zettelkasten to write a research paper about a formal field, where you need to carry along the proofs and demonstrations you’ve built over time. But not all of us need those demonstrations in the activities where we use our notes. More often we need the final byproduct, not the intermediates, if we don't explain our reasonings to others.

And it could happen than with the prompt system you reach more...

I would evaluate systems more in terms of effectiveness—in this way, the value of a system is tied to the goals of its author.

I personally find Luhmann’s system highly ineffective for me, and he would probably find mine ineffective for himself, but I could never say that Luhmann’s system wasn’t productive, or powerful. We run two different kind of races.

I don't think it's possible to make a ranking in terms of absolute values between the systems we have considered (mine, yours, doto, Luhman, etc). They present a too strong link with their author, link that implies a subjective dimension to its evaluation.

Great post, the Hindu Philosophy video has been on my to-be-watched for a while.

This post also related to a question I have been pondering lately. Would it be best to include a snippet (quote) of the source material as the "core" of an atomic note structure? Based on the reading techniques (here and here), I am able to reflect and synthesize my thoughts on the material before incorporating them into my ZK which protects me from accidental plagiarism and lazy writing. However, my worldview, approach, and skills are constantly evolving. So, then wouldn't be better to retain a snippet of source material in the ZK so I can constantly be formulating and relying on the actual data rather than my reaction to the data from the time of processing?

I would hate to get down the road in a few years and realize my treatment with an important concept was build on the foundation of my initial understanding taken from a literature note and not the material itself which led down a misguided path.

Everything before "if not even 'not a zettelkasten'" is roughly correct. But the last part is not true.

100%. There is also no evaluation in absolute terms. At least not on my side. I am simply stating that the prompt-style is not as powerful as the other one. If you don't need the power, you don't need the fully-fledged system. The fully-fledged approach is more costly, so it would be irrational to go with it even if you get what you want with the lighter system.

Unless you want to build upon your past work. Then you are left with code with no documentation. (Perhaps, in an even worse situation because you can't figure out exactly the workings of what you have written, since the writing is less formal than code. So, it is more likely that you need more documentation)

I don't understand.

Nobody is ranking anything in absolute values. I can imagine how you'd read that into my writing.

It seems to me that there are implicit social norms that established a hierarchy. Almost like comparing the sizes of Zettelkastens and feeling offended if I'd underestimate the size of someone's Zettelkasten.

Each to each his own. But that doesn't change different systems have different capabilities. This is what I pointed out.

I am a Zettler

With a seemingly more limited system, if it’s the one best suited to my inclinations, if it’s the one with which I manage to have the best feeling, I can achieve more than with a system that appears to be more complete and flexible.

It’s not a given that the seemingly more powerful method will fit me.

This dynamic becomes even clearer when we compare a Zettelkasten built on a computer with one managed through a physical slip-box.

The latter offers a thousandth of the possibilities of the former, yet you can find accounts of people who couldn’t get along with the digital version at all but found true fulfillment with the physical one.

With the “powerful” one, they produced literally nothing, they failed; with the “limited” one, they built their Zettelkasten.

I studied the dynamics of the physical Zettelkasten a bit in the past, and I managed to find explanations for why it works for some people. Their mind, in particular, found comfort in the physical constraints of the medium, and they benefited from being able to delegate part of the discipline required to properly follow the method to the medium itself. They benefited from the sobriety of the tool, which pushed distractions away, and so on. Some people need the safety of solid rails to be effective; they actually find them much more comfortable.

As I wrote earlier, if I remember correctly, we’re evaluating tools that support cognitive processes, not physical objects. By their very nature, they are intimately tied to the person using them.

Even when speaking in terms of “power,” using your term, yes, you can consider the theoretical power of the two tools taken in themselves, but what really matters is the power the author can actually harness with that tool.

If I compared a Ferrari with a Panda, I could say yes, the Ferrari has a stronger engine than the Panda.

But again, if I think it through: if I had a Ferrari, I’d leave it in the garage because I wouldn’t know how to drive it, I live in the countryside so it would often get stuck on the roads, and it wouldn’t be useful to transport vegetables :-).

In my context, not only would the Ferrari not be more useful than the Panda, it would actually be the worst possible choice I could make.

In my opinion, one could also say that theoretically the full-fledged method (I’ll keep using this term since I don’t know how else to call it) can more easily lead to certain developments compared to a prompt-based method, but the real measure of this potential only comes when you put it in people’s hands—and some of them might be able to prove the opposite, once the method is applied in practice, in everyday life. Behind this theoretically greater expressiveness, there are many dynamics that make it necessary to contextualize heavily.

To conclude, I think the two approaches should be compared in their entirety.

The idea that the full-fledged approach is more expressive than the prompt-based one for certain kinds of work and people is just a small part of the whole story.

I could basically define my Zettelkasten as full-fledged by default, but it also happens—and it’s actually quite important—that I work in a prompt-based way. And I do this because, in my experience, I’ve noticed that three things can happen:

Before we proceed, can we conclude two threads?

I don't want to put you on the spot. But that I want to close these two open threads.

I am a Zettler

For me it's ok to close these points.

I don't understand why you used this sentence in one post, in the economy of the discussion:

"If I write that something doesn't count as a Zettelkasten, I don't exclude the person from the Zettelkasten community. I am merely making a statement about the category of the thing I am seeing."

My reply was connected to that fragment, and we talked about making prompts.

Just for confirmation:

Full Fledge System and Prompt Based System, they both satisfy the requirements according to the core zettelkasten definition you have used during video with Nori?

For the first point, I disagree with your use of "power" in an absolute way, as I understood in the same fragment, and in another your statement, lacking the scope in the the same expression.

For what (specific) purpose, for whom, and in what way the author does makes the difference. Can't be "much less powerful to think".

It's like saying Ferrari is better than Panda "to move" :-)

I see two layers:

I mentioned this because it is arguable the most extreme example of the social layer of communication: For us humans, there is nothing that is more intense than complete social exclusion.

I am giving my explanation with my coaching hat on. I am not saying that the following is what is happening for sure or that there is any intention in that direction. I am merely describing a dynamic that I am seeing:

Taking a step back it seems to me that the underlying direction is "softening the blow", since you can (and many do) see in what I am writing a personal value judgment. To me, the contrast between "absolute value" as an indicator of a non-relational judgment and the more "reasonable" judgment everything is "valuable in relation to XY (e.g., goals) is one of the tell signs in coaching (more so in health and fitness) that one wants to avoid a hard conclusion for other motivations than the binary code true/untrue.

Another tell sign for the social layer starting to dominate an exchange of thoughts is an increasingly selective approach to replying. Examples:

The above dynamic is the major reason why there was social conflict. My part is to completely ignore the social layer which creates the impression of me being cold-hearted and mean (or disagreeable).

Here, my impression is that the social layer seeps into our discussion and hinders our understanding. (My clumsy English doesn't help either...)

I am saying that a Ferrari has more power and that you can drive slow or fast with it. With the Panda you can only drive slow. However, to drive the Ferrari you need to build your driving skills. I am not making a general statement about how to move better.

This is another tunnel vision aspect: In the article, I explicitly wrote:

I am consciously building substructures in my Zettelkasten that look very similar to the notes that I on surface level looked down upon.

So, my approach is exactly as flexible and divers as yours according to your description.

The actual claim of the article is that it is more inclusive and flexible to think about atomicity as a desired outcome. At the same time, it is also more powerful. So, the best of all worlds, because when it serves you, you can hit atomicity right away.

Basically, I am being "attacked" (I know that you don't attack me and I don't feel like that) for critiquing note styles that I am using explicitly myself.

The absurdity is complete if you take the reaction "Oh, this or that is not a Zettelkasten!" into account, while I am the one who is taking the inclusive take. (I said it to Nori, that I have a pretty loose and wide definition of what a Zettelkasten is, too)

(I said it to Nori, that I have a pretty loose and wide definition of what a Zettelkasten is, too)

I am a Zettler

Throughout the whole discussion I never really focused on the social aspects you mentioned.

The relationships and mutual considerations between the authors of different Zettelkastens are not particularly useful to me, to be honest :-).

I'm not a fan of any faction, I have no particular motivation to get involved in social dynamics.

The only human dynamic I’ve noticed—this applies in general Zettelkasten narrative—is that each author tends to place more value on the approach they personally believe in, whether consciously or unconsciously. This also happens because, mainly and quite simply, one uses one’s own method, while one observes the methods of others.

That’s human, perfectly legitimate—but when I need to analyze what I read, it’s something I have to take into account that something subjective could be contained in what I read.

I read and analyzed your essay with the aim of learning something more about the Zettelkasten.

From this perspective, I tried to identify the differences between the two proposed approaches, in the abstract.

I wasn’t particularly interested in how Bob Doto does his; even if he did it in a terrible way, that wouldn’t be my concern today, as my focus today isn’t there. It could just as well be a mediocre way of implementing a model, but I'm interested in the model, not in the particular implementation.

I spent many—really many—hours on this process of reconstructing the models, building a map of the two approaches: half based on what you wrote in your essay (thank you for the opportunity), and the other half by reflecting on the subject myself, using your statements as a kind of “stimulus” and reacting them :-).

It was a very constructive exercise.

In this process, by putting all the pieces together, I found some thoughts that seemed to be in conflict. And those are the ones I reported in the first post of the thread.

In short, then, in my reasoning there are no social dynamics involved. I simply find that some of the points you expressed about one of the two approaches, taken in the abstract, don’t quite add up.

A sentence like “The approach by these four fellas is much less powerful when it comes to using your Zettelkasten, so think” (so, for to here, a typo I think), when one of the four is Luhmann, I took it as if it were a sudden wall placed in the middle of the highway.

In my view of your example, this way you’re not using a Ferrari as if it were a Panda; rather, you have both the Ferrari and the Panda, and you use the vehicle that’s most suitable for the occasion :-)

If your reference model is the Full-Fledged System, and for a certain activity you’re building a Prompt System, then you’ve shifted from the Full-Fledged System to the Prompt-Based System—you’re no longer using the Full-Fledged :-)

And that’s exactly what I do as well, after all.

It’s not that the paradigm of the Full-Fledged System adapts to another situation—it’s the shift in paradigm that allows you to handle the situation.

In this reflection, I’ve left aside the potential problems that come with having to properly master two different models—I think I already hinted at this earlier, anyway.

It implies a certain friction in making choices, for example.

And in practice you end up having to learn two different ways of doing the Zettelkasten, at least if you want to do both of them at a high level. Having two, moreover, it’s hard to go in depth with both, unlike someone who specializes in just one.

Something that often happens in computer programming, anyway, I can add. There are languages that support multiparadigms, but rarely in high level practice do you manage to adopt them all well, and when you become really good at one you can almost eliminate its theoretical limits of following only one.

The ability to go vertical can be seen as another declination of “power.”

Putting aside Bob Doto and the other for a moment and focusing on Luhmann, I have reason to believe that if Luhmann had found any limits in the approach he was using, he would have included some other adaptations, and we would have seen a different slip box to study.

Or it could be that he did do something, but it’s not recorded in the only thing capable of telling us what he did—his slip box. Probably adaptations remained in his mind.

Given how much he produced, using his method (whole pieces of sociology and systems theory, from what I learned about him), this method while apparently narrow, can actually be remarkably broad.