Less than 100 notes and already feeling overwhelmed: I need help! :-D

Greetings,

I've been getting around the Zettelkasten method for about 2 years, but never dove in.

Now I did, and after less than 100 notes I already feel overwhelmed: when I create a new atomic note, I barely remember where to attach it (the advice is when you create a new note you should attach it to a previous one, is it?).

I don't remember the chains of thoughts, and I spend lot of time navigating my Second Brain in order to find the right note.

I've tried several formats.

- I've tried a file per each note and numbering it, such as 1.a, 1.a1, 2.a, and so on, but soon all the notes appeared the same to me, and I found hard to detect the paths of the notes

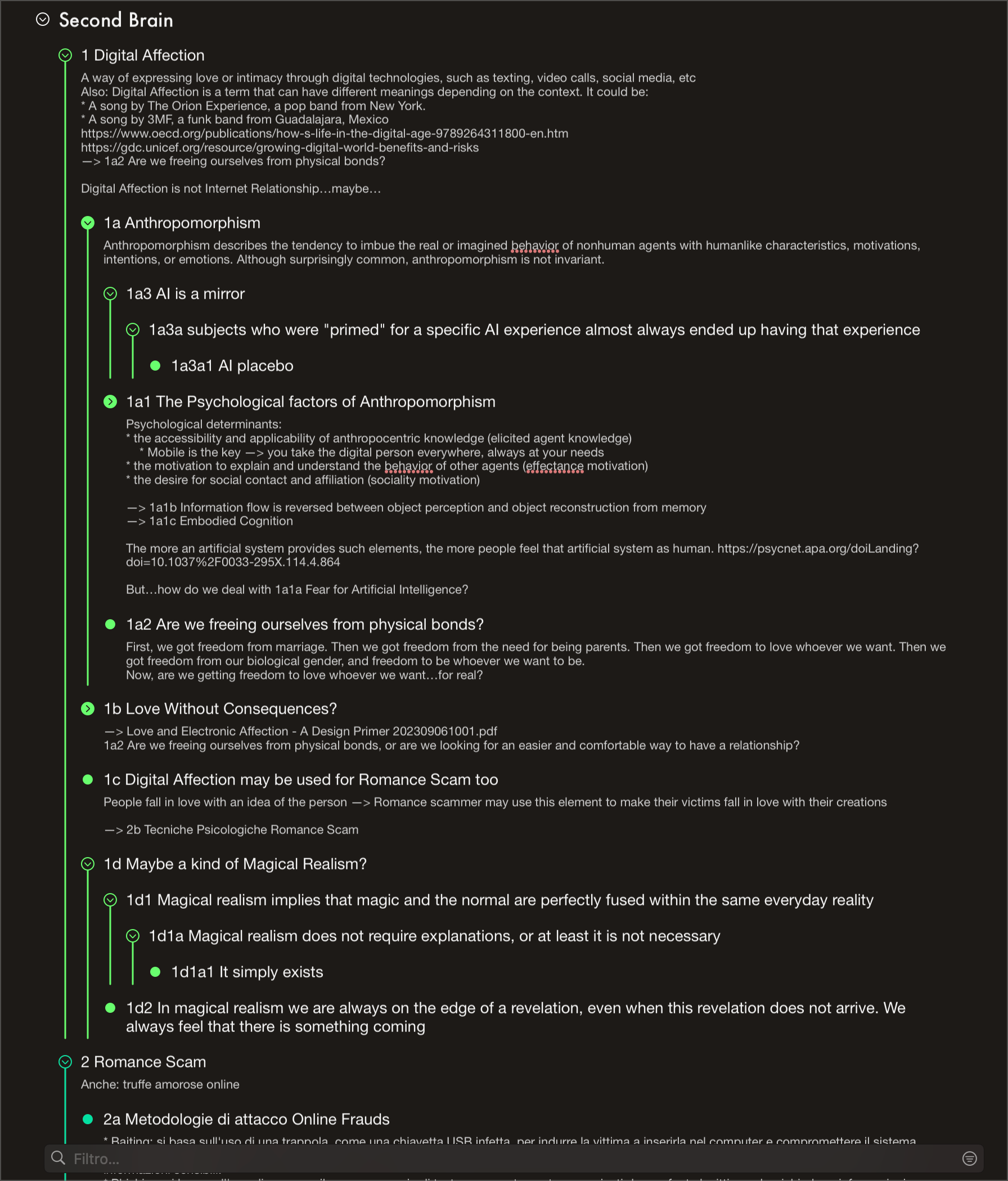

- So I've tried a single outline (see the screenshot) because I'm a visual person, hoping to have a visual clue of the structure of the chains of thoughts, but again I feel confused when I see all of those lines.

Furthermore, I need a fast way to insert the new note into the System, because I have no time to get the extra hour each day in order to review the notes (I'm always on the rush).

It results in dozens of notes laying there in the Limbo of the notes that aren't (and maybe will never be) processed.

I also tried a kind of PARA method, thinking of the opportunistic strategy, but I fear I'll have difficulties when searching for older notes.

Any advice is accepted.

Thank you!

PS: a screenshot of the outline...

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

Hi Ivan,

Using an outline is a good strategy.

If you don't feel comfortable with a single, long and complex outline (someone likes, I don't like) and become hard to manage it, you can simply break it in smaller outlines creating a note for each. Then, you can link every outline note in a more general outline.

You can decide to make this break when an outline grows too much, or organizing them before filling with bullets (I prefer the first strategy).

So, instead of a single outline you will have a forest of outlines.

From your picture, you can form three outlines,

When they grow too much, you split existing outlines again

For what it's worth, I think you're doing it right. You're interacting with most of your notes when adding new notes. That doesn't help you in your question though.

I have about 700 notes in my Zettelkasten and picked a few notes as "starting points". I have 14 notes that serve as the beginning of a chain of thought and help me find other notes just by following relationships. This works for me.

Another approach is start doing structure notes, where you create a separate note containing links to other notes. This requires maintenance on the structure notes, but that may be worth it. For me, my Zettelkasten isn't yet big enough for me that I need structure notes. Maybe someone else can tell you more about this.

I think the cause of your problem is the low depth of processing of your notes. You can get away with such a low depth of processing depth if you are very familiar with the domain of the notes.

If you look at Luhmann's Zettelkasten, you might ask yourself how his Zettelkasten works if his notes are that brief and erratic. It works, if you hear him talk about anything, it is clear that his Zettelkasten is not second brain or memory. He didn't need one. His Zettelkasten was both a creative tool and an aid to enrich his texts with citation which is a completely different thing most people are using the Zettelkasten for.

So, the solution to your problem is to actually take diligently processed notes. Based on your statement that you are always on the rush, the root cause might be in your self-organisation.

I am a Zettler

Nice tip.

I'd lose the global overview, but these outlines are searchable also form Spotlight (I'm on a Mac).

Structured note may be a good add because they may give more context to the notes, and context aids memory and elaboration.

That is, I should find some time to process the notes: I see it's a vital part of the System.

Indeed this is my main field: Cyberpsychology.

May I ask you what you mean for "low depth of processing of your notes"?

Can you please detail, or give me some examples?

I have two remarks:

First, if you instead of an alphanumeric ID use a timestamp-based one, there is no need to “place” the note anywhere. It should, of course, be connected by links, but I personally find that a lower pressure situation, because one note can be linked to many others and so be included in several trains of thought that are all equal. Using a Folgezettel makes it feel like one chooses a “default” connection.

Second, I’m not sure if I understood your process right, but it seems to me like you are attempting to keep the entirety of your Zettelkasten in your head, at least to some extent. You said you “don’t remember the chains of thought”. I think it’s a nice goal to be familiar with one’s notes, but I use a Zettelkasten specifically to outsource some of this remembering. I navigate it locally, rather than globally, I don’t need to see the whole maze, just the immediate surroundings. And if there is a chain of thoughts that I need to see in its entirety, I make it a single note with links to other notes.

I’m sure there are other and better ways of approaching this, but this is what works for me.

You might consider reducing the importance of "atomicity" - at least in the early stages of learning ZK. Give yourself permission to write fewer and longer, i.e. more "running text" notes that are numbered sequentially such as 1/1, 1/2, 1/3 etc., resisting the urge to branch and sub-branch every specific, granular thought that comes to mind. This practice of creating sub-sub-sub branches for such specific ideas seems untenable in the long run; will soon be a larger bowl of "spaghetti" as they say in the coding world.

Looking at your 1d Magical Realism notes, they could easily be one note for now. Alternatively, take these longer notes as "source or literature notes" and condense them later as shorter, main notes in the ZK.

As you process your notes in the ZK on subsequent reads, and as the information already in the ZK has incubated for a while, then you can decide to branch and supplement on "concepts" especially, such as 1/3a Magical Realism, resisting the urge to branch and branch every tiny idea.

You may also wish to think "higher on the ladder of abstraction", meaning focus on decisive concepts and ideas at a higher level, numbering just the key concepts such as Digital Affectation, Anthropomorphism, Magical Realism; with the smaller ideas, comments and opinions just being numbered in an easier sequence (or appearing in one (or few) note(s)).

There is a contradiction there. You wrote:

Whenever you work in a field that you are very familiar with, this shouldn't be an issue. If you are very familiar with the domain, there is an oversupply of ideas on how to connect new ideas.

If you are in an academic environment, there might be a strange phenomenon at play: There is a strange pattern that academics are one of the least able group of people being able to adopt a system for knowledge work. I don't understand that fully, but most likely it has something to do that the academic environment is about publishing papers, not doing knowledge work. The mind of an academic is trained to work in a specific environment for specific outcomes that are somehow detrimental to knowledge systems.

My current take on the academic environment is that it puts the people in a situation in which they are employing a lot of coping strategies, very often with success (paper get published, careers are advanced, etc.).

The natural reaction to anything that would involve changing those coping mechanisms is met with defensiveness.

I am writing this, just to make sure that I mentioned it, since the solution might not be tactical but strategical. You wrote that you are always on the rush. This leads into a second possible cause:

If your level of engagement with your knowledge base (I am using a neutral term since it is not Zettelkasten-specific) is not reaching a certain threshold, you won't develop the familiarity with that is necessary to develop the system specific skills to the level that puts you in a position that the basic actions are not something that you need to engage consciously. (e.g. use the software, find an entry point, the basic decisions on how to get into your system, quickly activating the relevant representations necessary to navigate your knowledge base etc.)

So, you might lack familiarity in two ways:

The ideas are not developed but seem to be added to an outline with the mindset of minimal commitment. One of the biggest driver of both increasing familiarity with the ideas and with their representation is the depth of processing. (I base this on level of processing model by Craik/Lockhart) This is represented by the level of curation of your notes.

This post has links embedded into the curation process.

There is an article in the pipe (I am waiting for the first editing feedback) that shows an example of what I consider a fully developed note.

The third point of resistance might be buried in this sentence:

Insertion is part of the management part. The knowledge processing aspect of connecting a note to your system is neither fast nor slow. It depends on the content of the note because it requires you to make a meaningful and valuable connection between two ideas.

There might be some tweaks that would allow you to add a note more quickly. But there is no trick to skip the deep and careful engagement with the ideas, both in your Zettelkasten and the ones that want to become part of your Zettelkasten, if you want your Zettelkasten more than just a container.

Containers, though, have certain traits that result from our relationship with it: Low familiarity. So, there is a decision to be made:

It comes full circle to the strange pattern I observe in the academic world: You need to decide whether to focus on short-term tactics or to focus on the long game. The long game means sacrifice.

From personal experience, I can tell you that the long game is totally worth it.

(Keep in mind that it is always an "it might be that" and not an "it is like this" when it comes to the actual facts of yourself)

I am a Zettler

@Sascha said:

I am not an academic, and I can't claim to understand academia either (first of all because it is heterogeneous across institutions and departments), but I am suspicious when when @Sascha claims that academics are "not doing knowledge work" and that they react with "defensiveness" when it is proposed that they do (what Sascha thinks is) knowledge work.

Since we are talking about psychology, I am reminded of how the inventors of motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick) at first relied heavily on the concept of "resistance" (resistance to change) in their theory, but later abandoned their reliance on that concept.1 Imputations of "resistance" or "defensiveness" tend to underemphasize the interpersonal interaction between the person making the imputation and the person who is the object of the imputation, and overemphasize the characteristics of the person who is the object of the imputation (such as emotionality, unconsciousness, or unreasonableness).1

Sascha seems to use the term "knowledge work" to refer to a kind of private activity, working on one's own personal knowledge. But academic research is primarily a kind of public activity, working on public collective knowledge, and I think that is just as much "knowledge work" as the private kind. (I am reminded of what Lorcan Dempsey called the outside-in and inside-out functions of academic libraries.) If academics are producing publications, then they are doing their job: they are doing public collective knowledge work by adding to the collective knowledge base (the collective hypertext). If they are successfully doing that job, and Sascha comes along and tells them that they should be doing his kind of "knowledge work" by building a private Zettelkasten (a private hypertext), then I would not be surprised if they meet his suggestion with "defensiveness". You can see how "resistance" or "defensiveness" is probably not the best term here, as the motivational interviewing people came to think. A better, and more intellectually humble way to describe it is a conflict or debate about what kinds of knowledge work are most important and how best to achieve them.

William R. Miller & Stephen Rollnick (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd edition). New York: Guilford Press. ↩︎ ↩︎

@IvanFerrero said:

I am thinking about what @IvanFerrero said about "formats" in relation to a comment I wrote recently in another discussion in which I said:

That comment may apply here too, except for the "Any format would be fine" part, because @IvanFerrero discovered that two "formats" did not seem to work for him. But it may help if you try to make a simple schema of note types and link types. The general idea of trying to make a schema of types is expressed in the title of Joel Chan's web page "People naturally try to enact typed distinctions in their notes". More technically, it could be called data modeling. Data modeling, or making a schema of types, is more abstract than the question of whether to use separate files or one big file for a Zettelkasten; you can use the same schema with separate files or with one big file (for example, various data-serialization formats can represent complex data models in one big file, but generally people in this forum want to use separate files because they are easy to manipulate in the usual file systems).

In fact, both "formats" that @IvanFerrero described above (separate files and one outline file) already have a simple and very general schema, because a hierarchical relationship—such as indentation in an outline—can be considered a type of link called "subsumption": A subsumes B. But that type of link is extremely general: What does it mean that A subsumes B? It could have different meanings for different As and Bs. If you could define a few subtypes of subsumption (or, more generally, define types of information units and relations) that are relevant to your work, it may help.

@Nori said:

When @Nori said "one note can be linked to many others and so be included in several trains of thought that are all equal", this is a way of encouraging you to think of your Zettelkasten as a graph, which is a superset of the tree structure that @IvanFerrero tried to use in his two "formats" above. Notice that if you use link types as I described above, you can have a graph with various tree structures specified by using different link types. All you need is software that can represent these tree structures for you. An example is the Breadcrumbs plugin for Obsidian, but the provision of multiple views of knowledge graphs is one of the most underdeveloped areas of personal knowledge base software. A view that can represent directed graphs as a hierarchy has been called transhierarchy, and there are not many software implementations.

@JasperMcFly said:

Again, making a simple schema, as I described above, can help you decide how much atomicity/granularity you need. If you start by doing some data modeling so that you have an established schema (beyond "A subsumes B"), it can help you decide where to "cut" units of information and decide how to relate those units.

This is not what I wrote. I wrote that the academic environment is about publishing papers, not that the academics don't do knowledge work.

The above is a common complaint of academics. I quote Hannah Arendt (grabed from Wikipedia):

"This publish-or-perish business is a disaster. People write things that should never have been written and should never be printed. Nobody cares. But in order for them to keep their job and get the right promotion, they have to do it. It degrades the whole intellectual life."

My assessment of the academic environment is by no means controversial

I cannot do much with it, since it is one concept from one theory. I could dump other perspectives on resistance to change on this quote, but this wouldn't be productive.

But resistance to change in the case of the change would mean leaving coping tactics behind is a phenomenon that can be observed in many areas, like addiction or problems with compulsion.

No, I don't.

The whole problem of academic research is that knowledge work and publication are two separate processes. This creates phenomena like "publish or perish"-culture, publication bias, the replication crisis etc.

In the light of the above, I reject this statement wholeheartedly. The act of publication can be not only damaging to the collective knowledge base (by selectively publishing or diluting the collective knowledge), malicious publication is a real phenomenon. I don't like to attribute this to the tobacco industry or the sugar industry. There are people, scientists, that are willing to do the dirty work.

So there is a spectrum from creating articles for the sake of creating articles because the system doesn't optimise for knowledge work but for publications (again, it is not in the least a controversial statement), to coping strategies for the knowledge work itself because the daily life of an academic is strangely hostile towards deep work that is necessary for quality knowledge work (a common struggle for academics that they complain about a lot) to malicious publication practices.

The premises are off:

In the light of the above, resistance and/or defensiveness might not be the best terms, but they accurately capture a slice of the psychological layer of the problem of knowledge work within the academics field.

By the way, the reason why I stopped pursuing an academic career was the reliable description of academics that there is very little room for actual knowledge work. When I talk to academics that are still in love of their research (which is hard in that environment), they are very envious for the capacity of my schedule for deep work alone.

William R. Miller & Stephen Rollnick (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd edition). New York: Guilford Press. ↩︎ ↩︎

I am a Zettler

@Sascha said:

Well, you literally said, "the academic environment is about publishing papers, not doing knowledge work." I had to guess what "not doing knowledge work" meant, but thank you for clarifying your position. A lot of good work gets published by academics, so there must be institutions or departments that are not so hostile to knowledge work.

I don't think that knowledge work is so private, or that knowledge work and publication are so separate, from the perspective of distributed cognition, wherein "mental content is considered to be non-reducible to individual cognition and is more properly understood as off-loaded and extended into the environment, where information is also made available to other agents" (Wikipedia).

Such "dirty work" is not public collective knowledge work; it is information pollution.

I read @Sascha as saying that academic incentives weigh in favor of publication and against Zettelkasten development. The relation between Zettelkasten and knowledge isn't entirely straightforward for me, however.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

@ZettelDistraction said:

I would point to a definition of knowledge from Ernst von Glasersfeld that I mentioned in a previous discussion with @ZettelDistraction:

As I understand it, pre-publication review by editors and reviewers intends to assure that academic publications are non-redundant to existing publications and contain conceptual structures that are considered viable by experts other than the author(s). So if an academic publication system is functioning properly, it will have applied enough methodological, epistemological, and ethical checks on the viability of the published conceptual structures (information) to reasonably call it new public collective knowledge, and it will not be producing information pollution. That is why it is reasonable to assume that if academics are producing publications in a properly functioning academic publication system, they are not producing information pollution. (It is true that there are predatory/deceptive publishers, content farms, and the like, but that is clearly not a properly functioning academic publication system.)

As for the contents of an individual's Zettelkasten? If the individual has applied some checks on the viability of the conceptual structures (information) in it so that they find them viable, then it's knowledge by von Glasersfeld's definition. That is no guarantee that other people will agree that it is knowledge.

Yes, I literally said that. But I hope the phrase without any ellipses would be like:

"the academic environment is about publishing papers, not about doing knowledge work.

I think that is a fallacy because knowledge work can be done in a hostile environment. That is my core criticism of the academic world: The work published is not a testimony of the quality of the universities etc. It is a testimony of small exceptional enclaves within the system and sometimes a testimony of the surplus work some people are willing to do.

Keep in mind that I am talking about something very specific: The actual processing step which is done in the minds of people. Surely, communication, collaboration etc. can and is utilised to facilitate or exploit (not in the negative sense) the processing.

But the actual locus of transformation of information and knowledge into knowledge is done in the mind of us. Yes, we have aids like thinking tools (e.g. paper, computer, abacus). Yes, we have collaborators. Yes, we need to collaborate and distribute the processing to be able to reach certain heights of knowledge. Yes, we benefit from certain contexts.

The fact that many processors are needed to accomplish a task doesn't negate the fact that the processors are doing the processing.

Yes. But the conditions are not met, which is my very point.

No true Scotsman.

PS: This is not about the Zettelkasten Method in particular. People that are in the acadamic field are less likely to use any knowledge base than for example managers. (from my experience)

PPS: Keep in mind that I rejected an academic career after learning that the university is an environment that is hostile towards knowledge work. This was the pretty solid consensus of the people I talked to.

@IvanFerrero Don't feel that your thread is hijacked. Just chime in. I will separate out the posts that are not directed towards your issue.

I am a Zettler

Too often I see this generic advice to use a timestamp ID, but no one ever mentions what affordance that practice provides or any direct motivation for doing it. In this context it's suggested to remove the need to place the note anywhere, but if this is the only benefit, why bother having an ID at all? What other tangible benefits does a timestamp ID provide? (If the only benefit is having a record of creation, then why bother to put it into the title, which usually only causes confusion and problem in most digital systems? Digital systems have much better places to store date/time created, modified, etc. if you need them for search.)

In Luhmann's case the alphanumeric ID gave direct benefits in organically creating neighborhoods of ideas in which one could easily travel and which provided concrete, findable locations for search and linking. This appears to be part of the beneficial structure for what @IvanFerrero has, so why suggest such a change @Nori?

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

>

I completely agree that with modern digital systems there usually isn’t a need for an ID at all. I considered this option when starting a Zettelkasten, but opted to include a timestamp in the filename mostly for future-proofing. In case I will ever need to switch software or use printouts, timestamp ID seems to be common enough to likely facilitate such migration.

But yes, for me the main advantage of timestamps is that they provide an ordering without implying any hierarchy.

>

The reason I suggested a time-based ID is that @IvanFerrero expressed difficulty with finding the right location for new notes. I know that the Lumanesque IDs do not imply hierarchy and the relationships they create are not supposed to be more important than those created by links, but for me personally (and I suspect some others too), that is exactly what they do (subconsciously). It puts more pressure on putting the note in the optimal place.

I do appreciate the neighbourhoods of ideas that these alphanumeric IDs create, but here again they lead to prioritisation of certain links over others. That is why I prefer to use a local graph view to visualise these relationships. I know graph view is controversial and I don’t think it’s a necessary feature, but I do like it specifically for this purpose.

@Nori said:

I would add that the reason for this is because the Lumannesque IDs create a single hierarchical tree structure where every note has only one location, and if you view that tree as an outline (or just as an ordered list of files in the file system), there may be relations between notes which should be as visually salient as the tree relations but will not be salient. What @Nori wants (and I agree is better) is a more general directed graph structure. A directed graph can be viewed as an outline with transcluded subitems, but you need software that is capable of a transhierarchy view, as I mentioned above.

@IvanFerrero may want to consider together several issues that have been mentioned: (1) how he is processing notes, as @Sascha mentioned; (2) what his data model is (a simple schema of note types and links: see Joel Chan's conceptual model and practical guide, for example), as several people have mentioned using different terms—the issue of tree versus graph is part of this; and (3) what software system provides the most helpful visual representation—does he want software that supports a transhierarchy view like Roam and Workflowy? He would want to resolve issue 2 and 3 in a way that supports issue 1.

Sorry if I hijacked the thread above with the discussion about academic "knowledge work"; I hope it was entertaining if nothing else.

@IvanFerrero

Your notes remind me of mine. And I think that there is some truth to @Sascha’s arguments. You should slow your process down. For example, the “interrogative” notes (the ones that end with questions); have you returned to them lately and tried to answer them? Or collect and source any information that may help you answer them?