Mortimer J. Adler's Syntopicon: a topically arranged collaborative slipbox

Robert Hutchins, former dean of Yale Law School (1927–1929), president (1929–1945) and chancellor (1945–1951) of the University of Chicago, closes his preface to his grand project with Mortimer J. Adler by giving pride of place to Adler's Syntopicon. It touches on the unreasonable value of building and maintaining a zettelkasten:

But I would do less than justice to Mr. Adler's achievement if I left the matter there. The Syntopicon is, in addition to all this, and in addition to being a monument to the industry, devotion, and intelligence of Mr. Adler and his staff, a step forward in the thought of the West. It indicates where we are: where the agreements and disagreements lie; where the problems are; where the work has to be done. It thus helps to keep us from wasting our time through misunderstanding and points to the issues that must be attacked. When the history of the intellectual life of this century is written, the Syntopicon will be regarded as one of the landmarks in it.

—Robert M. Hutchins, p xxvi The Great Conversation: The Substance of a Liberal Education. 1952.

Adler's Syntopicon has been briefly discussed in the forum.zettelkasten.de space before. However it isn't just an index compiled into two books which were volumes 2 and 3 of The Great Books of the Western World, it's physically a topically indexed card index or a grand zettelkasten surveying Western culture. Its value to readers and users is immeasurable and it stands as a fascinating example of what a well-constructed card index might allow one to do even when they don't have their own yet. For those who have only seen the Syntopicon in book form, you might better appreciate pictures of it in slipbox form prior to being published as two books covering 2,428 pages:

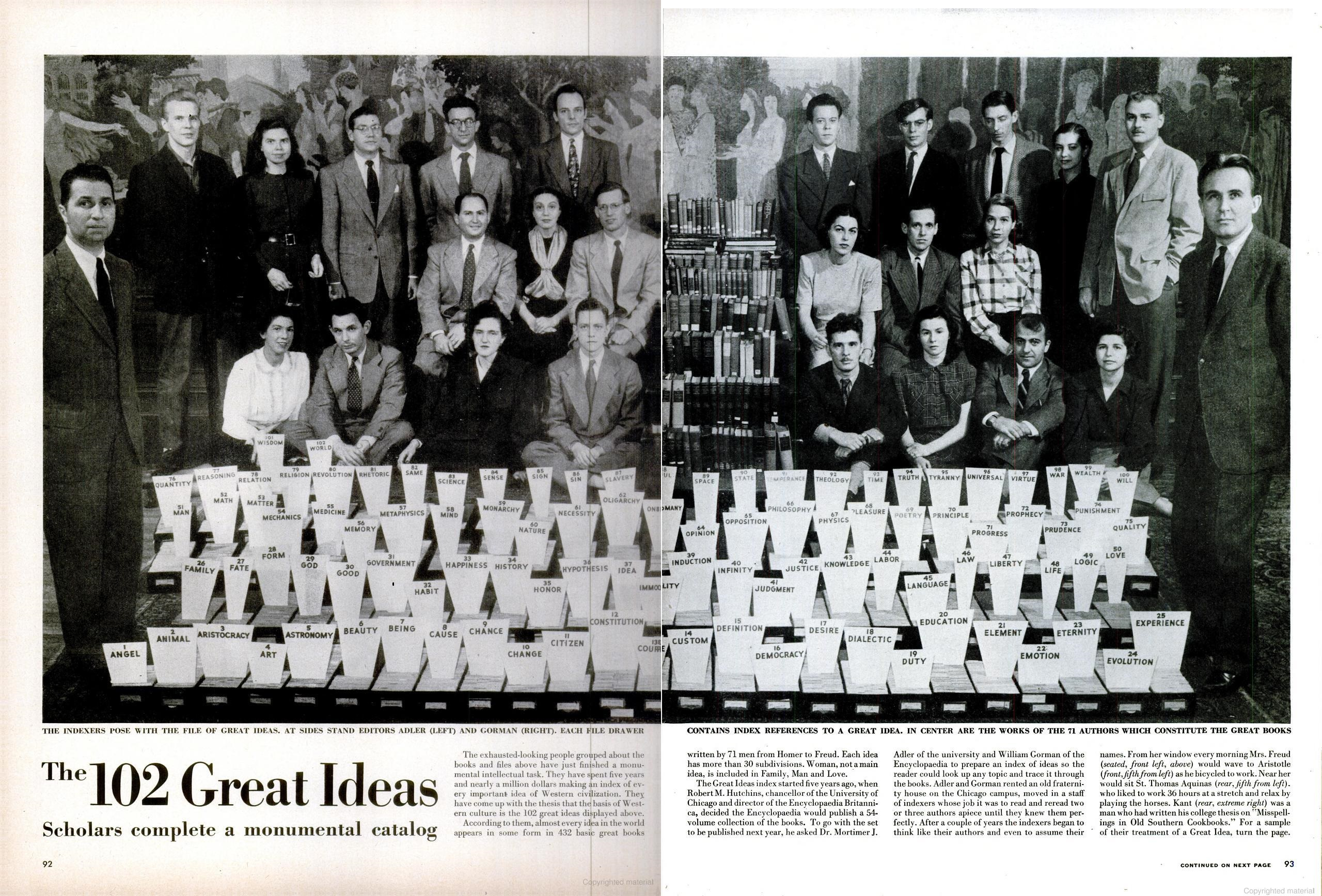

Two page spread of Life Magazine article with the title "The 102 Great Ideas" featuring a photo of 26 people behind 102 card index boxes with categorized topical labels from "Angel" to "Will".

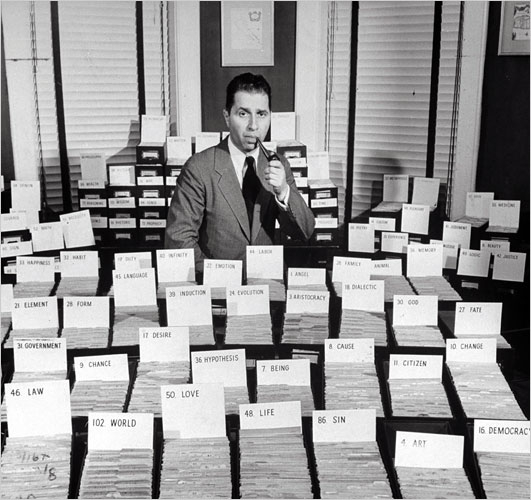

Mortimer J. Adler holding a pipe in his left hand and mouth posing in front of dozens of boxes of index cards with topic headwords including "law", "love", "life", "sin", "art", "democracy", "citizen", "fate", etc.

Adler spoke of practicing syntopical reading, but anyone who compiles their own card index (in either analog or digital form) will realize the ultimate value in creating their own syntopical writing or what Robert Hutchins calls participating in "The Great Conversation" across twenty-five centuries of documented human communication. Adler's version may not have had the internal structure of Luhmann's zettelkasten, but it definitely served similar sorts of purposes for those who worked on it and published from it.

References

- LIFE. “The 102 Great Ideas: Scholars Complete a Monumental Catalog.” January 26, 1948. https://books.google.com/books?id=p0gEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA92&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false. Google Books.

- Hutchins, Robert M. The Great Conversation: The Substance of a Liberal Education. Edited by Robert M. Hutchins and Mortimer J. Adler. 1st ed. Vol. 1. 54 vols. Great Books of the Western World. Chicago, IL: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

No piece of information is superior to any other. Power lies in having them all on file and then finding the connections. There are always connections; you have only to want to find them. —Umberto Eco

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

@chrisaldrich My late uncle Bob introduced me to Adler and the Great Books when I was a boy. Thank you for reminding me: Mortimer J. Adler & Charles L. van Doren edited a version of the Syntopicon organized as a book of extended quotations from the Great Books, titled "A Great Treasury of Western Thought" (ISBN 0-8352-0833-8). I will quote a revised version of my Amazon Review. The Amazon picture was from 2002 when I had hair, but the revised text below reflects my aerodynamic noggin.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

By happy coincidence, I just happened to read an amusing anecdote about Mortimer Adler in "The Situation of Philosophy in the United States" in Rudolf Carnap's intellectual autobiography (The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap, 1963, page 42):

Assuming that Carnap's encounter with Adler did not occur before the compilation of the Syntopicon, it suggests that having a massive collaborative Zettelkasten does not automatically transform a person into a critical thinker.

Carnap continued:

Peculiar indeed! The Great Books, and the Great Treasury of Western Thought which came after and both of which Adler edited, quote Darwin at length:

Perhaps Adler was skeptical of Darwin's theory. He certainly knew about it!

Adler worked in the Aristotelian and Thomist traditions and was considered a lightweight and a crank by many professional philosophers. So, unfortunately, yes. An Adler-sized Zettelkasten offers little or no protection against motivated reasoning.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

Carnap said:

@ZettelDistraction said:

Suddenly one notices that Chapter One of the Synopticon is "ANGEL":

The article is followed by ten pages of small-print cross-references to angels in the Great Books.

Carnap again:

The Wikipedia article tells us about the Synopticon:

I see that in my previous comment I twice misspelled Syntopicon as "Synopticon", a Freudian slip due to fusing the word with panopticon in my mind, perhaps due to the aspiration to omniscience shared by the Syntopicon and panopticon—an aspiration that we will more perfectly achieve the more we emulate the angels.

Is it possible to set aside the business of angels and minds without bodies, and enjoy the rest? The criticism that the Great Books can be reduced to argument reminds me of certain approaches to Zettelkasten. From the Wikipedia article on the Syntopicon.

My uncle Bob had a similar attitude: he preferred to read the philosophers and avoided imaginative literature.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

@ZettelDistraction said:

It's possible for some people, perhaps. As for me, Adler already lost me in Chapter One. Since he wrote all the other chapters, and since I have a backlog of thousands of other things to read, I will pass on a detailed study of the Syntopicon. No thanks!

I don't know to which criticism this sentence refers. The criticism is certainly not mine, since I don't even believe in "Great Books" (that is, although I think some books are great, I've never seen a list of Great Books that I agreed with). But Adler's supervisor Robert M. Hutchins, in a passage in the original post above, claimed that the Syntopicon is

This seems to imply that angels are an important "problem", an "issue that must be attacked". I'll be frank: I don't agree. I will decide for myself where the problems are and where the work has to be done; I don't need Mortimer Adler's direction.

If I stop thinking about its content and focus only on the form of the Syntopicon—its structure, design, and typography—I can enjoy and take inspiration from its form. I find its form beautiful and worth studying: it's a beautiful material artifact. But its content and methodology strike me as very problematic.

Someone who is considering starting a Zettelkasten today would benefit more from a critical study of Adler's book, titled How to Read a Book(Kindle, 326-7), than his Syntopicon, Propaedia. or Six Great Ideas.

How to Read a Book tells you how to take notes. The highest level is syntopical note-taking.

Here are the steps:

You should read multiple books syntopically only after you've learned how to read one book analytically. You read analytically by stating a book's propositions and critically evaluating the reasons the author gives to support those propositions.

The Syntopicon was a critical, financial, and intellectual failure. But you can apply aspects of Adler's method to great effect in the construction of a Zettelkasten. If you follow Adler's tenets, and look for the reasons the author gives to support the book's central ideas, you'll be well on the path to creating a well-connected Zettelkasten.

The internal structure is what made Luhmann's Zettelkasten special. It isn't just a minor aspect that makes his Zettelkasten a version of Zettelkastens. The internal structure made his Zettelkasten [Amber].

If the purpose is just to collect for publication, then yes. But Luhmann didn't collect, he integrated ideas. And his goal was something very different from a collection of ideas. He aimed to develop a true super theory, a theory that is so complete that it incorporates itself. (His theory laid even out how the mechanism of self-incorporation of itself was)

Not everything that is a Zettelkasten (German) is a Zettelkasten (English).

I am a Zettler

@Sascha said:

This is exactly why I talk about a "note system" or "knowledge base system" instead of a Zettelkasten: because these alternative terms emphasize the systematic aspect, how notes are systematized or how a knowledge base is systematized. The word Zettelkasten or slip box does not express the systematic aspect: as @chrisaldrich has claimed elsewhere, it is even a "Zettelkasten" when Eminem throws a bunch of random paper slips into a box.

As I mentioned last month in a comment on "What is the problem situation of the Zettelkasten Method?", there is something like a paradigm shift in the level of systematicity of a note system: "Before the shift, one doesn't think of one's notes or one's knowledge as a system. After the shift, one realizes that systematicity is intrinsic to one's definition of notes and knowledge." Philosopher Nicholas Rescher called this shift "the Hegelian inversion". Luhmann is an example of someone who had a highly systematic conception of knowledge, but today's work on knowledge graphs in computer science and knowledge organization (for which the work of Rudolf Carnap, whom I mentioned above, was an important precursor) provides perhaps even better examples than Luhmann.

I get that, and I appreciate that professional philosophers will likely find Adler's Thomist metaphysics and his "curation" off-putting, but I wasn't suggesting a detailed study of the Syntopicon. I was reminded of Adler and van Doren's Great Treasury of Western Thought, which I find a helpful book of extended excerpts from the Great Books, whatever you might think of Adler's addled methodology. (I couldn't give a rat's asshole about Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels, and Angels.) Also, Adler does not begin with an essay on angels in the first chapter of the Treasury, which begins with a brief essay on Man. The chapter titled Religion is the last of twenty, and there is no essay or chapter devoted to "minds without bodies." Perhaps, when the Great Treasury of Western Thought was published, material considerations overwhelmed Adler's better angels.

To the blockquote from the New York Times Review, which I repeat here:

Also, see @Nido's post above for a related view of reading (one formulates a book's propositions--this seems to assume that a book is concerned with ideas that can be logically analyzed) and of the content and organization of a Zettelkasten (Zettels should have the statement of those propositions formulated in your own words; interconnection among Zettels should follow the evidence and argument an author provides for the propositions stated).

I will ask ChatGPT4 to weigh in since I am intellectually outgunned and suffer from acute mental lassitude and inanition. In the interest of transparency, this is my prompt:

This is ChatGPT4's reply:

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

@ZettelDistraction said:

I just looked at the Great Treasury of Western Thought, which I don't think I had seen before, and I see that it has the good sense to begin with "MAN" instead of "ANGEL"! It looks like Dr. Adler learned something in the intervening decades! I've seen other anthologies of quotations like this, and they can be helpful. The Great Treasury categorizes the quotations in a taxonomy. It has a better overall organization than the Syntopicon and has the advantage of providing direct access to excerpts from the source texts, unlike the Syntopicon, but has the disadvantage of taking the quotations out of context. Today in a well-designed knowledge-base system such a disadvantage could be eliminated by transcluding the text fragment in the taxonomic document while providing a hyperlink to the text fragment in the context of the source text. Digital hypertext is such a better solution to the kinds of knowledge-organization problems that people like Adler were trying to solve in the mid-20th century.

When thinking meta-systematically about knowledge organization systems, it's helpful to keep in mind the kind of rubric provided in several figures in Maria Teresa Biagetti's article "Ontologies as knowledge organization systems" (in Knowledge Organization, 48(2), 2021, 152–176, and in the Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization), for example:

The scientific ideal of someone like Carnap is the level of axiomatic theory. But as Figure 5 above nicely shows, the requisite level of organization of a knowledge system corresponds to its function or purpose. The purpose of Adler & Van Doren's Great Treasury is to provide excerpts from existing literature that provide entry points to that literature, for which a taxonomy is a sufficient level of organization.

Here again a matrix of options such as Figure 4 and Figure 5 above can be helpful: one's methodology and knowledge organization system (and its level of precision) should correspond to one's purposes. There are some kinds of knowledge that can be captured in language but not in an argumentation scheme, much less in an axiomatic theory. And there are some kinds of knowledge that are not well captured in language at all, and are better captured in video and/or animated diagrams. There are a range of qualitative research and visual research methods that should be considered.

@Andy said:

I was just wondering: Could we extend Figure 4 to higher levels, such as a multi-agent system? That level would be far beyond our humble individual note systems, but considering that real life is already an organic multi-agent system, it may be worth thinking about how that level relates to our note systems. I already think of my note system as an element in a larger multi-agent system—the distributed cognitive system that we're already living.

@Andy said:

This is also one function of qualitative data analysis software (QDAS), which is why people use QDAS to do literature reviews.

Thank you for your remarks on QDAS--I was unaware of this software. BTW I think we are being unfair to @chrisaldrich. I agree with him that the cross-referenced card system Adler et al. set up for the great books series did serve at least one of the functions that Luhmann's Zettelkasten served--publication. I don't think we're guilty of abstracting away essential differences by saying so.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

@ZettelDistraction said:

Agreed. I wasn't trying to put down @chrisaldrich's contribution, but to add some additional thought to it, in a meandering conversational way. Adler and colleagues did produce publications (the Syntopicon etc.) using their massive collaborative index card file, but what they were doing was closer to what is done by librarians (who index and categorize literature) than to what is done by those writers (I'll call them philosophers for lack of a better term) who produce articles or monographs with an argument or theory that evaluates the grounds for and against presumed knowledge. (Or, better: Adler at al. were aiming for a middle way between librarian and philosopher—an idea I'll revisit in a moment with reference to Tim Lacy.)

This librarian-versus-philosopher distinction seems to me to correspond roughly to the lower end and the higher end of the scale in Figure 4: Levels of ontological "precision" (Guarino 2006) mentioned above. "Lower" and "higher" here refer only to conceptual systematicity, not to value: both ends of the scale are valuable. The virtue of the low end of the scale is democratic inclusiveness, and the virtue of the high end is epistemic precision and systematicity (or such, at least, is the hope of the philosophers and scientists who aim for the high end). The middle of the scale combines the librarian and the philosopher, because taxonomy is cataloging but requires some philosophical analysis (in contrast to mere enumeration or alphabetization, for example).

I was googling to find critical essays related to the Syntopicon, and I discovered that Tim Lacy has written several works that emphasize the democratic inclusiveness of the Syntopicon project, beginning with his dissertation (Making a democratic culture: the great books idea, Mortimer J. Adler, and twentieth-century America, Loyola University Chicago, 2006). Here are relevant passages from his article "The Lovejovian roots of Adler's philosophy of history: authority, democracy, irony, and paradox in Britannica's Great Books of the Western World" (Journal of the History of Ideas, 71(1), 2010, 113–137):

The democratic impulse of Adler and colleagues, however much it may have been compromised, is very similar to the mission of public librarians. Here's how François Matarasso expressed that mission in "The meaning of leadership in a cultural democracy: rethinking public library values" (LOGOS: The Journal of the World Book Community, 11(1), 2000, 38–44):

I've been motivated to write all this because I can feel the librarian-versus-philosopher tension in my own thinking: there's a part of me that wants to embrace ALL THE BOOKS (like the democratic impulse in Adler), and there's a part of me that wants to formulate the most precise and systematic philosophy that is possible for me (like the scientistic impulse in Carnap).

@Andy, I am impressed with your research on this and @chrisaldrich's research on the history of Zettelkasten. I should point out that there is a level below the lowest level in the scale of ontological precision, namely, my random effluvium, indicated in the revised scale below.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

I second that. In my mental map of the new note-taker land of the internet, @chrisaldrich is The Archivist. The place to seek if the adventurer needs long forgotten knowledge.

If somebody likes to use RPG-Maker to create a game inspired by the landscape of the new note-taking, I offer me as a free consultant.

I am a Zettler

Marshall McLuhan apparently saw the referenced article in LIFE magazine and analogizes portions of zettelkasten to coffins and headstones! From his first book The Mechanical Bride (1951):

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

@Sascha said:

What are the other ones?

@chrisaldrich is hopefully nearing a point when his archive spills out into a monograph...will it be 2025?