Note Typology

Lately I've found Bloom's Taxonomy interesting — Bloom apparently did it to save time in making annual examinations (according to my source, at least) and consequently, it led to a "common language" for education.

When asked what's "the most important thing they want students to gain after each class," teachers will always say that they want students to "really understand" the lecture. But as Krathwohl (2002) put it, this is an ambiguous term; they haven't articulated what it means when a student "really understands."

And without a common definition of how well students understand the material, making exams that test understanding would produce large variability.

How do you even know when students "really understand" something?

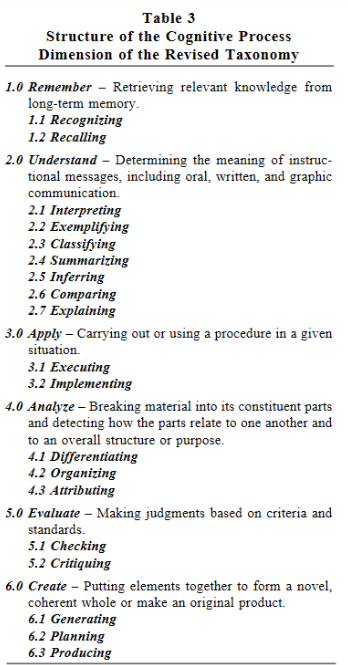

So what Bloom's Taxonomy did was give a comprehensive set of criteria at which teachers could determine whether a student could "really understand." In the latest revision, discrete levels of 'cognitive processes' were used:

The higher up the students are in the cognitive process dimension, e.g. if the student can "apply," not just "remember," the 'deeper' the learning is. (I've found this taxonomy useful in my personal learning as well.)

Of course, it can be argued that the cognitive processes may very well be a continuum rather than a bunch of defined levels, but the point is that Bloom's Taxonomy has led to a common language in education that clarified what it means when students "really understood" what they were trying to drill into their heads.

In the Zettelkasten Method, I realized that there may be much overlap between the concepts to create a taxonomy that creates this 'common language,' as in Bloom's Taxonomy.

But, I feel like a note typology, at least, may be especially useful to beginners. (Note: Not trying to say I'm intermediate/advanced or something)

Why beginners? My motivation here is that when I started using the Zettelkasten method, I did feel the need to have clearly defined "types of notes" — a sort of recipes to follow — so that I can adopt the principles without getting overwhelmed. I'd slowly discover my own "note typology" after a year, but that's only after I was able to connect the principles, my observation of how others were doing it (by lurking in the forum, stalking @Will's post like a creepy madman, and binge watching Christian process "Range by David Epstein" at least 3 times), and my own experience in making chaotic notes.

My hunch is that having this typology would reduce a beginner's learning curve, and help them figure out how to integrate principles into their work much better.

Now, for the current notes I have, this is my "typology":

- Notes/Zettels/Atomic Notes - they contain just one idea, elaborated in your own words. (I've started hating the term 'Evergreen notes') They could be definitions, a claim, or a how-to. This is not exhaustive, just what I remember from my notes at the top of my head.

- Concept structure note - these are structure notes that link to a set of notes that form an argument. For a familiar example, a concept structure note named "Wheat may be poisonous to bears" would contain the atomic notes "Wheat contains 10% gluten" and "Gluten is poisonous to bears"

- Outline structure notes - these are writing outlines that contain main points or questions for an ongoing writing project, such as my Master's Thesis or an online course I'm making. These main points allow me to do a more laser-targeted search when reading. I know what to extract before I read.

- Source structure notes - these are structure notes that mostly use the source material's structure to organize the notes. I usually take notes in here while reading, (See @ctietze's video on Range — he does this, too) but I've decided to just take notes on my Kindle so I can stop straining my wrist

- Buffer notes - "special" note that doesn't really have structure, but rather contains my raw thinking that I'm not sure whether to integrate or not in my archive. Hence, a "buffer"

- Home/Startup note - it's where I link to the structure notes I'm actively working with so I don't have to think about where I need to go or more importantly, how I need to continue (the extra thinking adds resistance for me)

As much as possible, I avoid using fancy terms to avoid confusion, and just call the note what describes it, in plain language.

So I have a question for the more experienced:

Do you have your note typology? Do you think we should agree on a common language for the type of notes we make? More importantly, do you also think that having a typology is even helpful?

Personally, I feel like it would put everyone on the same page, especially when posting on the forums. But at the same time, I also realize that "getting stuck on terminology" is also a trap — but that most likely happens when definitions are too ambiguous.

Ref

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

This issue is close to what I said a couple of days ago about ontology and domain-specific ontologies in computer science (check out that comment if you didn't notice it—and if you don't like the term ontology, then feel free to substitute some other term like semantic schema).

There are many relevant ontologies that one could use to organize one's note system. The venerable IBIS and the more recent AIF are two that have inspired the organization of my own note system.

I think the answer to the question "should we agree on a common language" is: No, if we are not working together on a common project, then we do not need to agree on a common ontology any more than we need to agree on a common markup language.

The philosopher Nicholas Rescher in his book The Strife of Systems: An Essay on the Grounds and Implications of Philosophical Diversity concluded that diversity of conceptual systems is inevitable due to diversity of values such as importance, centrality, and priority.

Yes, it is helpful to know what ontologies and ontology languages are already available, because one may be trying to solve a knowledge organization problem similar to a problem that has already been solved with an existing ontology.

I was just thinking about this very topic yesterday.

Here's a rough taxonomy of my current note types, which is very much a work in progress:

Started ZK 4.2018. "The path is at your feet, see? Now carry on."

@Andy I'm confused about what you mean. As you've considered, not everyone is working on the same project. Similarly, not everyone here would be familiar of the concepts you're referring to. Are you simply/in essence saying that we should get inspiration from existing knowledge management systems?

@Phil your "braid" analogy seems perfect. ah, now I'm starting to see that developing a new typology would interfere with others' existing typologies. But in essence, we have the same types of notes — except the project note. I'll look into your link

ah, now I'm starting to see that developing a new typology would interfere with others' existing typologies. But in essence, we have the same types of notes — except the project note. I'll look into your link

@alcantal said:

I tried to provide lots of links to further information in case any of the terms I used are unfamiliar! Ontology is like a superset of taxonomy: a taxonomy that has further properties (or semantics), such as relationships and attributes, would constitute an ontology.

Well, knowledge management software refers to a particular software implementation. When I talk about ontology I'm talking about something conceptual: it may have a formal specification but is independent of a particular software implementation. I am saying that, yes, I find it helpful to have an ontology in mind even if the software I am using does not force me to use that ontology (this is my case), and when developing an ontology it may be helpful to consult existing ontologies and ontology languages.

@Andy of course, but hopefully it's just me. I went through the links and still didn't get your message. Not an attack, btw. Anyway, to get to the point, the wide scope of taxonomies (let alone ontologies) is why I specifically referred to note typologies. I thought that going to taxonomies would make the topic more abstract rather than concrete, and that's not as useful for beginners.

Also, I referred to knowledge management systems, not software. So essentially, you're saying that you do have your own ontologies in your Zettelkasten work inspired by existing ontologies, is that correct? Did you go to existing ontologies to get ideas for your system when you started your zettelkasten?

More practical question:

What's the note typology you have and how would you define them?

All the same type: Zettel. Each has a header, a body and a footer. Typology is for me an arbitrary additional structure, much like a coordinate system in geometry, that can be imposed later.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

@alcantal said:

Well, you also talked about taxonomies; you said: "In the Zettelkasten Method, I realized that there may be much overlap between the concepts to create a taxonomy..."

The topic of ontologies is relevant because in a note system many of the notes are related to each other, and there may be different types of relationships, and the notes may have other properties as well, so I don't think it is off-topic to bring the term ontology into the conversation. If one is going to specify types of notes, why not specify types of relations and types of attributes as well? Something to think about!

I know, but since the purpose of my response was to clear up any confusions, I thought I should clarify that I am not talking about a particular software implementation.

Yes, as I mentioned, my note system is very much inspired by IBIS or dialogue mapping, which I also use separately in other work. Here is a diagram of the IBIS ontology from Wikipedia. I am so familiar with it that it is almost impossible for me not to use it. There is a similar research taxonomy from the classic book The Craft of Research, which I read when it was first published decades ago, that I keep in mind: topics, questions, problems, claims, reasons (and their warrants), evidence, objections, and responses to objections—most of these closely overlap with the IBIS ontology. Recently I've begun investigating AIF too to see what I can learn from that. And there is more I could mention.

I have avoided answering this because my note system is much broader in scope than what most other people on this forum are doing; my note system is (or aspires to be) what David Allen (of Getting Things Done fame) called "an integrated total life-management system". It is too detailed and intimate to describe here. But given such a wide scope, you can imagine why I would find an ontology helpful.

This is me as well. I have atomic notes. Notes links to other notes. I can pick any note and follow the incoming and/or outgoing links to create trails. Some minor tooling helps automate this to create outlines.

I probably have all sorts of types of notes, but don't really feel the need to classify them as such. For now it's been working well.

Although it is important to differentiate conceptual typology/taxonomy/ontology from particular software implementations (as we mentioned above), it occurred to me while looking again at @alcantal's note types in the original post that the features of one's software can influence one's typology/taxonomy/ontology.

For example, in contrast to @alcantal's note types above, I have:

So I suspect there will be at least minor, and perhaps major, differences in typology/taxonomy/ontology due to a person's choice of software. But my own ontology is more detailed than @alcantal's for reasons that are unrelated to software implementation.

Before posting this, that was also what I had in mind. Everything is technically just a note. Just ideas. There really is no "real distinction," so to speak, only ones that seem distinctive later on.

@Andy We already get that you have your own detailed ontology, but I was curious about examples of the rather distinctive typologies that have emerged from it to help condense the various functions of notes. You seem to have provided some upon citing The Craft of Research.

Anyway, my typology isn't the Zettelkasten typology, just as there is no such thing. They are just notes.

So my point here isn't to impose a rigid structure like what a strict typology or software implementation does, but rather uncover what others have already figured out so that beginners could have "springboards" to implement what we're already doing in a "recipe" kind of way, instead of getting overwhelmed in a continuum of possible options.

Automating outline creation from trails seems interesting, how do you do it?

I feel like my idea of this typology thing would create more confusion than clarity, but then again I wouldn't have figured this out if I didn't post it in the forums. Just thinking of "notes" may be better, and then having your own ontology emerge from how you want to integrate your knowledge work into your life, as @Andy says. (Thanks for the book recommendation btw)

On the other hand, a question still lingers: How would you teach a beginner when to create structure notes in their archive?

@alcantal said:

Aha! I misunderstood; when you said "common language" in your original post I thought you meant a single consensus taxonomy—that's why said I think the answer to the question "should we agree on a common language" is no. But the way you have phrased it here sounds like you are looking for a variety of note-system design patterns that could form a Zettelkasten pattern language (which is a collection of various design patterns). That would be a project well suited for a wiki: in fact, Ward Cunningham said that wikis were first "developed as tools to facilitate efficient sharing and modifying" of design patterns for software development.

@Andy The term design patterns seem to articulate it very well Curious about your implementation of IBIS. Can you give a few examples of your notes that interconnect general issue, argument, and position?

Curious about your implementation of IBIS. Can you give a few examples of your notes that interconnect general issue, argument, and position?

When I looked into it, it seemed simple enough, but at the same time, my impression is that it shapes the note content (similar to "layers of evidence") rather than the types of notes (w/ respect to the structural function) more, but I find it interesting nonetheless.

@alcantal said:

Sure, here's one example: I have a general issue/question note for business ideas that asks: What are potential areas for business models? (i.e. What are potential specific business models?) The connected position/answer notes are particular business models, each of which uses a common business model template. Then I have argument notes connected to the position notes arguing why each business model is good/bad (i.e. feasible/infeasible).

Another example is life goals. I have a topic note with a list of general life areas: health and fitness, interpersonal relationships, money and wealth, learning and personal development, citizenship and activism, and several others. They are not listed here in order of importance! I actually have a score next to each one for current level of importance and current level of satisfaction. Both scores fluctuate. Under each life area there are links to issue/question notes related to that area. This starts to get personal, as you can imagine, so I won't list the issues here. Connected to each issue are position/answer notes; many of them also have connected arguments but many don't because they are subjective so I don't really need to justify them. Some of the answers and arguments are connected to further sub-issues/questions.

I wrote a small python script that creates a directional graph with notes as the vertices and the links as edges between vertices. Creating an outline is picking a note and have the script follow the edges. Outlines can optionally be created within a radius of the first note.

I haven't been teaching people the Zettelkasten method, so this is hard to answer. I don't really have structure notes, since they're not atomic to me. I just write down the idea in a single note, in paragraphs and lists and include links as a natural part of the text. Structure is created from the links between notes.

The script I use helps with insight into the trail of thoughts, so I'm dependent on talking with my Zettelkasten through the script. I wrote and maintain the script, so I'm not too worried about losing this critical dependency of my Zettelkasten in 30 years. Even if I do lose the script, it's still just markdown files underneath and I could still follow the links manually.

I was burnt by categorizing notes before and probably won't be revisiting that idea -- but @alcantal's picture of the book with the categories is interesting to check the 'responsibilities' of a note or part of a note: "Is this an analysis? Am I criticizing? Should I add a plan?"

In my mind, that ties into separating description (phenomenon) from interpretation. Using these categories (and then some) as a cheat sheet could maybe be useful to learn to remember to check if one is mixing e.g. description and critique.

Author at Zettelkasten.de • https://christiantietze.de/

Maybe a useful metaphor: Think of some structure notes as a joining table for many-to-many relationships. In a graph (very cool library btw!) you would get criss-crossed links; with an additional structure note as a hub you can talk about the cross-crossing itself and bring it to attention.

Author at Zettelkasten.de • https://christiantietze.de/

@alcantal said:

I was just reading the Wikipedia entry on Bloom's taxonomy, and the last paragraph of its "Criticism of the taxonomy" section says:

This is an interesting criticism of Bloom's taxonomy: It suggests that Bloom's taxonomy gives the appearance of a common language, but there is wide variation in how different educational institutions interpret and implement the taxonomy. This fact is relevant here because it suggests that the kind of diversity of note-system design patterns that has showed up in our discussion here is also present in the educational learning outcomes that Bloom's taxonomy tried to standardize. Even when different educational institutions say that they are using the same taxonomy, they are interpreting and using it differently.

A bit off-thread topic, so apologies in advance.

As someone who works in higher ed in an administrative capacity and who is charged in part with overseeing assessment practices in my college, I can identify with this insight. I am skeptical of Bloom's taxonomy, especially because of the unthinking and transactional manner in which it's applied as a template onto curricular structures and practices in everything from chemistry to creative writing. This one-size fits all approach suits the compliance-driven needs of assessment professionals (I don't count myself as part of this fraternity, btw), but doesn't really do anything to capture the realities of how students learn or let faculty know how well their carefully-designed curricular structures and pedagogical experiences actually do what they think they do in this regard.

It would be far more effective if we adopted a general tripartite schema (along the lines of the one sketched out by Christian to which I refer in my post upthread), and allowed individual disciplines to modify it accordingly.

Started ZK 4.2018. "The path is at your feet, see? Now carry on."

Hadn't thought of it in the cheat sheet 'angle' before, but now that you say it, those processes do fit very well into the layers of interpretation that we use when making notes.

@Andy I wouldn't call it a fact based on just Wikipedia, but anyway, it's not that important for the discussion. And the Bloom's Taxonomy mentioned there probably refers to the unrevised one. I'd still think it's true, just as we use different terms (or not at all) for the same "note archetypes" that exist in our archive.

Maybe I'll look into it in the future, specifically how useful this taxonomy really is for learning. In my case, it was useful in creating better prompts for Anki.

@Phil I kind of understand your point, because people can absolutely evaluate or create something without really learning it. But I guess the point of (the revised) Bloom's taxonomy is that learning is more robust when you can create something out of what you learned as compared to just remembering the facts or concepts alone.

I don't know the full context, though. My motivation for learning it in the past was merely to help me create better questions for spaced repetition.

I remember you saying it in one video: (non verbatim) structure notes capture the thinking process you get upon stringing together a bunch of notea in your head. For example when you see three notes form an argument, capturing that thinking process may give the possibility of that argument turning into a book. But when you don't capture it with a structure note, it gets lost and now you have to start that insight from scratch. (I can't quite explain it well...)

@alcantal said:

Your statement here relates to your other question, Processing research that's based on shaky assumptions?, although here the evidence is not experimental. The topic of defeasible reasoning is relevant both to this statement and to your question in the other discussion. My use of the term "it suggests that" is equivalent to "defeasibly". It means that prima facie I consider that the evidence reported in the cited source (Newton et al. 2020) refers to observations that indicate the relevant facts, but this conclusion could be rebutted with sufficient counterevidence. It is fine to make these kinds of assumptions; we have to make such assumptions all the time, although they are defeasible. In this case, Wikipedia is accurately summarizing (part of) the source, and the relevant evidence in the source looks good to me. We know that we have to constantly question and evaluate everything on Wikipedia, and I did that before I quoted Wikipedia in this case. (Also, I wouldn't quote Wikipedia in more formal writing, for various reasons, unless I were writing about Wikipedia, but in an Internet forum? No problem. I think it's good to cite Wikipedia in Internet fora because if we determine that Wikipedia is wrong, then we can go to Wikipedia and fix it ourselves!)

I bring here this recently added post "Discourse Graph and Zettelkasten" https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/2509/discourse-graph-and-zettelkasten#latest , once @Andy mentioned this existing thread.

David Delgado Vendrell

www.daviddelgado.cat