The Friction Fallacy • Zettelkasten Method

The Friction Fallacy • Zettelkasten Method

The Friction Fallacy • Zettelkasten Method

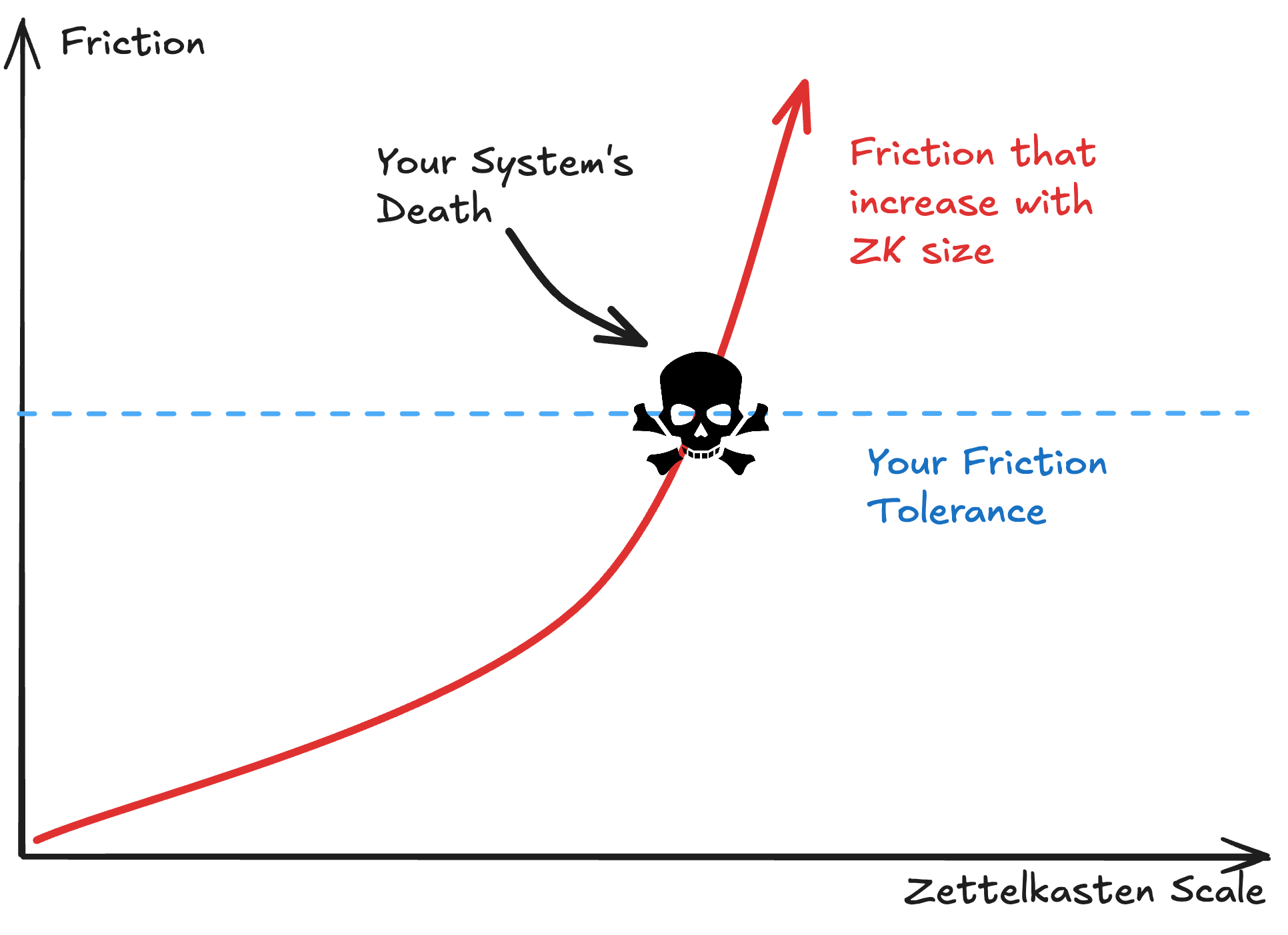

Friction is not a friend. Friction is either an enemy or a beneficial evil. Don’t commit the Friction Fallacy! Set up your Zettelkasten so that it runs smoothly for the rest of your life.

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

While friction may seem fascinating, if it produces the same results, one must consider which is more effective. This reminds me of when I used to process large amounts of data at MS Excel in the past. I used to solve data that could be processed with simple operations by using complex formulas. Also, if it costs similar, you should choose a better one. it's a matter of considering opportunity costs, but it seems too easy to forget them when you're fascinated by the means.

The demon test thought experiment shows that the structure notes are key. So, does your upcoming English edition cover the practical use of structural notes in detail?

Over the years I've restarted my Zettelkasten a couple of times, either in terms of tools (The Archive, Obsidian, etc), or the processes. But eventually it falls apart (which is probably when the itch to start over sets in).

Reading this, it became clear that it is about increased friction. In my latest iteration, I use a simple outline in Bike 2. But just as you point out in the article, Sasha, the folgezettel method eventually becomes to rigid – and I'm already experiencing this once again.

On a tangent: I think that (local) LLMs might provide a new reason to go with as atomic notes as possible. I've used them to dig up orphaned notes in my old folders, and incorporated the findings in fresh structured notes. And with atomicity, my intuition is that the models (be it embedding models or LLMs) more readily find relevant stuff.

Indeed. Folgezettel is by far not the only source of increasing friction and scale-fragility.

Ha! I wanted to write a short newsletter on Bike as a solution to create a Luhmannian Zettelkasten.

I have a hunch why this is. I'll send out a couple of emails that will be ignored.

I'll send out a couple of emails that will be ignored.

I am a Zettler

Another revelation I had over the holidays, as I started to explore what Claude Code can help me with:

I've always been a fan of open file formats, for what they mean for future-proofing access to your notes and not being locked in a specific tool. And the combination of plain text and scripting with Python, JS, etc also allows for a lot of customisation. At least for those who know how to write code.

Not being a programmer myself, not in any meaningful way at least, the latter has only been a theoretical benefit for me personally. In practice, that have meant to I've been limited by the features of my tool of choice (and possibly that 3rd party developers provides in plugins). And that also inevitably means that I have to adhere to what others thing are best practices or what features they have time to implement.

But with what I've seen from Claude Code over the last few days, and thanks to the plugin system for The Archive, it certainly seems plausible that I (or Claude, rather) can develop a couple of small scripts that reduces even for friction for how I want to name my notes, link them, work with metadata, etc.

Really excited about this.

@thoresson That sounds like an interesting use case. I captured exactly one convincing experience report of using AI to aid in the Zettelkasten Method. The rest was too low-return for me (or even damaging).

So, I am looking forward to your experience report and hopefully to you being 50% of my repository of positive AI-assistance.

I am a Zettler

As an avid and strict user of folgezettel I can say with experience that your representation is fair and accurate. If it helps as a use case for others, I use a layered approach to folgezettel. All my zettel start out as basic UUID’s that link to others and to outlines. For many notes this is all they get, and that works fine out of the box. As I refactor them they graduate to be referenced in linked zettel (usually multiple) that have Luhmann-like folgezettel ID’s. These act as a second layer of metadata that also helps me not get lost. I can see granularity and I don’t have to wonder how many layers deep an idea goes just from looking at the structure note (the side panel with the file names will show me). But this is secondary and friction-inducing for sure. For this reason folgezettel are an additional option as I refactor a note in the direction of a particular line of thought. The Luhmann-like ID denotes that particular direction, but the original zettel can operate on its own without these constraints. As can structure notes, which also may be placed in a line of folgezettel, structures upon structures, methods upon methods. I may have said this elsewhere but folgezettel work for me as an emergent way of surfacing what will become structure notes. Ultimately structure notes are the easiest and most flexible so if you can cut out the middle man, you maybe should. But the middle man has served me fairly well, and I need to figure out why that is.

I have to add that your system looks really wild. The idiosyncrasies were very hard for me to understand!

My guess is that you were persistent in learning the mechanics, part of the friction is reduced by skill and muscle memory, and now you have a medium friction, highly conditioned sub-workflow that provides you with an external reference for your thinking processes.

The risk is that you reached a metastable local maximum of benefit. It may be that you would improve your system by temporarily accept reduced effectiveness during a relearning phase.

However, if you exceed the desired productivity, you are not annoyed and there is no rising friction (if FZ is just a pre-staging phase and the results are feed into structure notes which protect you from scale), I wouldn't bother to change it.

It might be that you just have a complicated workflow of feeding the structures in your Zettelkasten.

I am a Zettler

I think you are correct. Folgezettel is a pre-staging phase that does result in the zettelkasten being more of septic tank (in Luhmannian terms) [which is why I don't recommend it for the faint of heart], but the breadcrumb trail helps me steep or percolate (coffee or tea?) on the subject over time before structuring it in a structure note or draft (or both).

Friction fallacy sounds nice. Alliteration plus rhythm makes a term that might catch on.

I agree that debates about friction become more meaningful, if we distinguish categories. But it might also be helpful to be aware of language. The concept of friction touches several domains:

With these domains in mind, I'd talk about the categories more like this:

I consider intentional friction positive, when it serves the system's purpose.

But is the friction itself positive or are you sacrificing smoothness for another effect? All your examples are about friction being the cost to create an effect.

So, I don't see the support for the notion that friction itself is beneficial, yet.

But let me steelman your statement:

Still, I have to disagree. With not considering the opportunity costs to other solutions, this judgement is premature.

To give you a real-world example: A typical advice (that I am also giving) is to never store unhealthy food in your home. To eat unhealthy, you then have to go to a store and buy it. So, the recommendation is to create friction to reduce availability of unhealthy food. However, this still leaves you vulnerable to situations in the store (not wanting to buy sweets is easier at home than in front of your favourite chocolate bar in the store and after a stressful work day), at social events, etc.

Few people take the challenge of identity change that would eliminate the need for friction to control your behaviour. The introduction of friction to solve eating behaviour also introduces the danger of accepting the lack of control and/or the unfit* identity. Typically, the reasoning is "I have no self-control. So, I take these measures." Often it is both a factual statement and an act of settling for treating oneself as a less capable person.

*Fit as the degree of adaptation to the environment.

I am a Zettler

Another example of controlling your behavior through friction is using an analog Bullet Journal as your task manager.

Task management doesn't scale well with the number of tasks. The more tasks you accumulate in a system, the more effort it takes to maintain them and the harder it becomes to make good decisions about what you should actually work on.

An analog Bullet Journal avoids this accumulation problem by deliberately introducing friction. Because it's analog, maintaining long task lists has a cost: you have to rewrite them by hand every time you migrate. That friction incentivizes you to keep only the tasks that are truly valuable and to discard those that don't add value (simply to avoid the effort of rewriting them).

That said, the real goal in task management is to make the identity shift that the Bullet Journal method points toward: becoming someone who proactively limits the number of tasks they take on.

In my case, I'd ideally prefer my task manager to have no friction at all (to the point where I could organize my tasks just by thinking about them). However, the friction of my Bullet Journal is quite low in my day-to-day life, and I'm not fully convinced that digitizing it would actually result in a net reduction of friction. So, for now, I'll keep my task management system as it is in my analog Bullet Journal.

Still, I think it’s extremely valuable to ask:

Creative work doesn’t play by conventional rules · Author at eljardindegestalt.com

PHYSICS:

I like to differentiate between friction and frictional loss. Friction is a form of resistance. Frictional loss is the energy consumed by working against friction.

ECONOMICS:

a) I think what you call the cost of friction is actually the cost of frictional loss.

b) Metaphorical friction is too abstract to measure.

But for metaphorical frictional loss we can use time as a simple proxy. The cost of frictional loss is the extra time we need to perform a task, when we fight unnecessary resistance.

c) Time is a limited resource. You have only a limited time budget available for your Zettelkasten. So it makes sense to spend it wisely.

The simplest way to not waste your precious time on a Zettelkasten, is to not use a Zettelkasten at all. If high friction prompts a user to abandon their Zettelkasten, it lowers their cost. Zero time spent = zero cost.

c) The only downside of this decision is that they don't get the benefits of a Zettelkasten. But how do you measure the benefits of a Zettelkasten? How do you know, if the time spent with your Zettelkasten was worth it?

PSYCHOLOGY:

The value of a Zettelkasten is highly subjective. Many people lead happy and productive lives without a Zettelkasten. :-)

a) Some people have a good time with a paper-based Zettelkasten, because they enjoy the overall experience. If someone enjoys the process, it's not friction! They don't fight resistance. They don't spend extra time fighting something that stands in their way.

b) For others a non-digital Zettelkasten is pure friction. They value the efficiency of digital tools with clickable hyperlinks and full text search. Paper makes everything more complicated, and they hate it.

So two people can use the same tool for the same task, but perceive it very differently. What is friction for one, is an intrinsic reward for the other.

c) The 1-million-bad-notes-scenario doesn't make sense to me psychologically. Why should people optimize for a scenario, they don't care about? The ideal of scalabality creates friction, because it adds a cognitive load. (I like @FernandoNobel's example of Bullet Journal as task manager. There are so many things you don't have to think about, if you keep it simple.)

ECONOMICS:

The scenario doesn't make sense economically either.

It's the difference between a hobbyist, a small commercial workshop and a factory. If you bake a single cake at home you need different tools and processes than if you bake 100 cakes or 100.000.

The economies of scale require changing the technology with increasing volume. You can't process 1 million notes by hand. You need automatization.

PSYCHOLOGY:

Which brings us back to the why. Why should anyone want to design a note-making system that is scalable to 1 million notes?

Why should a creative writer care, who enjoys writing with a fountain pen on beautiful stationary and who experiences a deep sense of purpose when interactiong with a few hundred cards?

ECONOMICS:

a) When you compare cost and benefits of a Zettelkasten, what do you place in the benefit column?

b) I agree that such a comparison would be useful, if we were comparing different solutions to the same problem. The redditor in your article is solving a different problem than you are with the 1 million bad notes.

TL;DR: Friction can prevent frictional loss. What counts as friction and what counts as benefit is highly subjective.

Please do! I understand the benefits of UIDs, but the Luhmannian number just works really well for my brain. I am interested to see your comments on this.

I had this experience just yesterday in my new, physical ZK which was really exciting. the repetition helps me chew on the content and actually process it. For now the friction works because I am too tempted with straight UID and full text searching.

coffee please

Hi Sascha,

Thank you for this article. I found it really pertinent and I agree with you.

I don't practice analog Zettelkasten looking for frictions, but because it relieves a part of it for me : working with pen and paper is possible for me after work, but screen is too tiring for me.

I spent a lot of time looking for relieving frictions from my analog Zettelkasten. It took me one year. I don't do Folgezettel at all : I only directly branch cards when they form the part of what would be the same note in a digital version. I have pieces of notes linked together as a whole thread (like would be a thread in Twitter) with the simplest UID form I can use.

For example, I have notes about my John Truby readings.

All of this subparts would exist on a digital note, I just put them into individual small cards.

I don't care about the limitation of the size of cards, as I branch them as a whole note. The next note about Truby or whatever about writing novel would be "DRM.260120/2" I don't ask myself where to put it. I can use this system even if my day was tough and I had a migraine.

Yes, Johannes Schmidt says that Luhmann filled the ZK only sporadically after 1992/93.

But… does this mean that Luhmann stopped using the ZK? Do we have proof that he didn't consult the ZK anymore? Maybe he just used it differently?

And there's Luhmann's radio interview with Wolfgang Hagen in 1997. I find it relevant for two reasons:

First we don't know if he stopped using his ZK. He could have switched to a hybrid system. He'd still consult the ZK for the material he had collected in the previous 40+ years. But he'd combine it with a simpler method for new material.

Second I don't think that the ZK has reached a point of failure in 1992, but that Luhmann's needs have changed. In 1992 he had reached the legal retirement age and retired from his university position.

I don't think that hard work and friction are the same thing.

Even if you had a perfectly efficient Zettelkasten, you'd still have to do the work of reading, understanding, choosing, thinking, connecting and learning. Knowledge work is cognitive work. Thinking is hard work. Writing books is hard work.

If you're lucky, you find a note-making system that makes knowledge work easier by providing useful structures and tools. It saves your energy, because it fits your needs. It might even increase your energy, because you enjoy it so much.

If you're unlucky, you have a note-making system that makes your work harder. It wastes your energy (frictional energy loss) and makes you feel bad.

Update:

I found this passage in Luhmann's manuscript Lesen Lernen (machine translation):

Work costs time ("Arbeitsvorgang, der Zeit kostet"). Work takes time. If you want a Zettelkasten, writing notes and finding a good place for them is necessary work.

For Luhmann the work is worth it, because it solves a problem: "Reihenförmiger Anfall von Informationen, die verfügbar bleiben sollen." And he also sees an intrinsic value in it. It's an opportunity to write. And it's an opportunity to train the memory.

It is a simple and straightforward way to evaluate if your Zettelkasten is robust to scale.

I am a Zettler

Have you actually tried to design a note-making system that can handle 1 million notes? I'm curious how this would look like in real life.

Yes. My Zettelkasten would pass the test easily. You could dumb the entirety of Wikipedia as text files (with IDs) into my Zettelkasten and it would result in some minor inconveniences.

The Archive is tested with 100k notes for performance. I dumbed it into my Zettelkasten as a test. So, technically my Zettelkasten is proven to be robust against the 100k note demon. But 1 million notes wouldn't make any difference as far as I can see.

So: Done. It looks exactly like the modern Zettelkasten Method presented here.

I am a Zettler

You mistake a tool for the method.

We seem to agree that a million notes would require a digital tool instead of paper.

And we seem to agree that affordable software exists, that can easily store and navigate 100k linked notes. (I tested 100k successfully with Obsidian. For 1 million notes I'd use a database instead of plain text files.)

But even if the software is super fast, the ZK method requires by definition some human thinking. ZK is a method to think and write in a particular way.

Assuming we have 1 million bad notes in The Archive, how would you refactor them?

How does your software support that process?

How do you identify "bad" notes?

How do you fix them?

I am not mistaking the tool for the method. That the software is able to handle that many notes, is just a necessary condition. It is the method I am applying that makes it possible for me to just continue working as if nothing happens.

Throwing in the 100k notes, didn't change anything of my work.

Nothing changes. I don't identify anything. I don't fix anything. If you'd throw 1 million notes in my Zettelkasten today, I'd continue working as if nothing happened.

The last time I checked Obsidian it didn't meet the threshold of performance with the 100k notes. (With my own Zettelkasten, which is much more densely linked it was even worse) So, this is good news if they increased their performance in the meantime.

I am a Zettler

Unlikely. A million bad notes would add so much noise, that you wouldn't be able to make meaningful connections any more. The system would break down.

You admittedly keep "abominations" around with incompatible character encodings and broken structured data. This adds friction to search.

How would you find relevant notes, that aren't explicitly connected to your favorite entry points?

There is no room to argue about this. I literally tested it with 100k notes that I dumped into my Zettelkasten and then worked with it. (with IDs) As I said above. Ten folding the note dump wouldn't make any meaningful difference.

So, if 100k notes barely make any difference, why would 1 million notes create do the trick?

I am not talking theory here.

I am a Zettler

Can you describe your tests in more detail? What was the content of those 100k notes? What test cases did you run?

I planned a demonstration of this test in reverse: I will start with a 100k note archive and just start a Zettelkasten. There you'll see the process in motion.

I am a Zettler