How did you become smart?

Hello, forum members, I'd like to hear your advice.

Here's what I'd like to ask:

1. I'm curious how you became so intelligent.

2. I feel like I don't have enough time to truly understand and think about things while working on other things. What's your solution?

I think you seem competent and intelligent. I'm curious how you became so intelligent. Do you find the time to reach that level of thinking while juggling your day job and daily life?

1. I'm curious how you became so intelligent.

I've been monitoring this forum since 2022. Most of the posts on this forum were incomprehensible to me. They were too difficult for me. I didn't even understand the topic the person who started the discussion was talking about. However, you wrote your thoughts on them with clear evidence. Because of my limited understanding, for the first two years, I worried that commenters were going off-topic and just saying what they wanted to say. However, as I became more familiar with Zettelkasten, I began to understand a little bit more, and when I returned to the forum, I realized what a surprising number of questions and answers there were.

However, the discussions here seemed to be not just about mastering the Zettelkasten Method, but also about philosophical, epistemological, historical, and scientific issues. It seems to me that all of you, the forum members, are skilled in logic, philosophy, and science. I'm often surprised to see you cite papers in your responses (e.g., @Andy). Where do you find the time to review so many?

I don't think you're seriously discussing something that isn't important or relevant. I think you're discussing it because there's a real issue. I wish I could think logically, philosophically, and scientifically like you. Perhaps I'm just trying to frame you as a straw man, thinking you're good at logical thinking when there aren't any such people on the forum. But that's how it seems to me at this point. What I want is currently very vague. I'm not sure what I want either. I just vaguely figured out where to go when I'm struggling. I'm a complete beginner right now, so I'm lost.

2. How can I reach such a high level of thinking while working? Do I have the time?

I'm an industrial worker. I think logically, but I'm not a philosopher. However, reading this forum and Charlie Munger, I realized that if I'm going to make a claim, I need to be able to defend it against counterarguments. Watching online discussions, I've seen many people make claims based on inferences without proper knowledge and then believe them. And those claims don't last long. Through that experience, I realized that skepticism, or scientific skepticism, can help solidify a claim.

But I don't have the time. Reading @Sascha's post convinced me that accessing primary sources and thinking directly would lead to better results, so I tried that for a year. However, the cost was far too high compared to the benefits. I used to think that to claim certainty about something, I needed to be able to explain it better than the opposing view. However, the more I tried, the more I realized I couldn't truly claim to know anything, so I kept digging, but without gaining anything. Is it important to know when to stop?

Considering these two things, do I lack the ability to select what is important? While I certainly have areas of expertise, they aren't the ones discussed in this forum. Is it unrealistic to expect that I should spend time in my areas of expertise while maintaining logical thinking, philosophy, and scientific skepticism, and strive to present my own arguments in the forum discussions? Am I actually hoping for the impossible?

What should I do? I seek your help.

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

The more you learn, the more you realize how much you don't know.

This has been said in various forms and attributed to different people in history, but apparently Einstein said it too, which makes it even more quotable.

Many of us here are in a similar position to you, working full-time in something unrelated, or not directly related, to what we study in our spare time. But we do what we can.

If you only have a little time per week, or per month, that's fine too. There are more books, articles and other resources to read/cite than anyone could ever cover in a lifetime. So we try to get better at choosing which resources we spend our time with, aiming to choose for both relevancy and usefulness.

Just this morning I started a book on 'Research Design & Methods' and got that familiar feeling of: Now I understand that I barely understand the basics!. It happens with any area we explore.

The trick is that it all adds up over time. When you keep going, finding useful information and connecting it to other useful information, you end up with a knowledge base that has both breadth and depth. But it takes time. It can take several years, but you do get there when you keep going.

If you're not sure where to go next, one suggestion would be something like Choosing and Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research. That website has many free books, so you might get other ideas there.

Ultimately, I realized that considering opportunity costs becomes important, as I don't have time to read everything. Thank you for your response and sharing the information.

I agree with what @wjenkins81 said! "We do what we can." "We try to get better at choosing which resources we spend our time with." "It all adds up over time." All very true. But I would change "It can take several years, but you do get there when you keep going": that is true in relation to a particular goal, but with regard to becoming smart, wise, knowledgeable, etc., I would say, "It takes a lifetime, and it is always unfinished". It's called "lifelong learning". I caught the research habit when I was a teenager, and I'm in middle age now. So when you see me spouting references in the forum, I'm drawing on a knowledge base of decades.

Earlier this year someone else mentioned in the forum that he had been diagnosed with OCPD, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (informally, perfectionistic personality disorder). I looked up the description of that disorder, and the traits sounded quite familiar from my own experience. You probably shouldn't be as obsessive about learning as some of us are!

I learned that it's important not to become too obsessed with perfectionism, but to simply view it as a lifelong task and work on it one day at a time as a daily habit. Thank you for the advice!

@iylock, I too admire the level of intelligence I see here.

I'm looking for some way to make sense of the vast amount of stuff (I think that's a technical term) that I encounter in life and on the internet. There are many things that are easy for me to filter out - I know that I'm not interested in them or anything like them. There are some things that I'd like to understand and learn more about. I'm sure that there are many other things that I have yet to encounter and may or may not find any value in them.

A few years ago, I encountered GTD (Getting Things Done). I saw some of David Allen's Youtube presentations and then ran across his books at the bookstore. I've read a few of them, at least one many times. He has managed to identify and document many thoughts on how to capture, prioritize and act on things "to do". He continues to create content and share it. I'm amazed by how simple he makes some things. I've been able to get some value for my life by internalizing some of what he has shared.

Also, in my travels, I've stumbled across the Zettelkasten concept(s) and a bunch of other related methods and tools which I'm still trying to sort and sift and figure out some thing(s) that will help me with the vast quantities of stuff that I would like to explore and apply. Like you, I keep returning here because of the high quality of the content shared by all kinds of folks.

I recall a sermon that I was blessed with hearing, many years ago. The minister suggested that one should hang around with people who are smarter than ones self. I've tried to apply that to my daily life and this is one of those places where I feel like I learn a lot, just by observing.

Thanks to all who make this possible and all of those who share.

@dgarner As the other two commented, it seems important to do what we can. Because You can level up only if you do what you can at your level. Thank you for sharing your journey with Zettelkasten.

This forum by nature will attract a larger than usual ratio of people who are very interested in the philosophy and/or science of knowledge.

Not "everyone" on this forum is posting that deeply, different deep posts are likely coming from different nerdemographics, most people who are confused will lurk rather than question.

Whichever niche people are "very smart" in that brought them to Zettel-K, this may be one of the few opportunities they have to communicate that knowledge to a receptive audience. Plus you're reading their thoughts in much more detail here - warmed up slowly over their keboard - than you'd hear around the water cooler - where they'd likely cut themselves off before their colleagues' eyes glaze over.

And... I mean, sometimes I enrapture rooms full of people with my insights. Other times, like now, my brain feels fried to a crisp. If work is consuming your brain cells, it's okay if just trying to learn a new tool/system has their legs wobbling.

Maybe in another phase of life you'll get some slack at work where your brain will supple enough to log back in and understand what people here were going on about. Or maybe you'll take that energy, log off, and walk your real legs out to touch some grass outside instead.

This place isn't the only measure of a mindfully invested life.

Regarding this point, I always wonder — when someone finds one of my writings difficult to understand — whether the problem lies in the subject itself being too complex, or in my own failure to explain it clearly enough.

I tend to think it’s almost always the latter :-).

If you say you didn’t understand something, I see the problem in myself, not in you.

I believe that when a concept remains cryptic, the issue lies with the writer.

I feel this as a real issue, but especially on Reddit — the other place where I talk about zettelkasten stuff — I almost never get feedback on my posts (“I didn’t get this,” “I have this doubt,” “this part doesn’t make sense,” “you explained that poorly”), and without feedback, I can’t adjust my aim. Feedback would be helpful for the reader, of course, but it would also help me improve my communication. And it's a bit frustrating, I confess :-)

Regaring your main question, I think that in this forum there are people who have made what you read here either a passion or even a profession — rather than it being a matter of higher or lower intelligence. These are ideas and readings that are part of their lived experience, their studies, their works. So it’s perfectly natural that there might be some displays of expertise in areas like philosophy, logic, epistemology, and so on.

I wanted to write these two points to give a more accurate context to the difficulties you mentioned in reading certain topics. I don’t think it’s a question of intelligence; some subjects simply have a very high entry step (they require a significant amount of time to grasp, at least),instead of having a gradual ramp, enough context, and clarity for a newcomer , and some users are true experts in their field and write accordingly.

So, it’s experience into a field rather than intelligence.

In any case, the Zettelkasten itself is excellent for tackling a “challenging :-)” forum like this one.

With a bit of patience, you can extract not only ideas from a discussion but also questions, doubts, reflections, terms to look up, and topics to explore. Every single point (question, doubt, unclear aspect) can be tackled and resolved, and once resolved, it is combined with the others like a piece of a puzzle. Step by step, the Zettelkasten keeps track of all your progress.

As I read @wjenkins81 has already explained the fundamental concept about: "The trick is that it all adds up over time". And Zettelkasten is formidable for this.

At the beginning, almost everything was incomprehensible to me (I work in IT); I found some topics understandable and useful only when I came back to them a second or third time, once I’d gained more experience.

At the beginning, I didn’t even know what “epistemic” or "mental model" meant — not exactly the words you hear at the bar.

@andang76 After reading your comments, my thought was that ultimately, the only way to learn in that field is through continuous effort. You mentioned that you work in the IT field, and although it may vary depending on the field, I understand that in the IT field, you basically need to continuously learn the latest information. What is your own way of studying IT while also studying fields related to Zetelkasten? I suspect you might not have enough time to study.

Yes, time is an issue. And I need to manage that issue.

In the IT world, whether you like it or not, you’re forced to keep learning all the time: investing time in staying up to date is simply part of the job.

That’s why it’s important to learn how to use that time in a more rational and intentional way.

It was by analyzing how the Zettelkasten method affects my daily work that I began to understand just how powerful it can be.

I realized that thinking deeply (because writing forces you to think, to analyze and break down what you’re learning) and documenting what I do and think while I work takes more time at first, but I end up gaining that time back later.

I can reuse my past work multiple times: I understand it better, I remember it better, and I’ve kept track of situations, questions, and problems I’ve already solved.

What’s written stays. Memory fades.

Let me give a simple example.

Until not too long ago, when working on a project or a task, I would simply look up articles, book chapters, or tutorials, apply a solution to the problem at hand, and move on.

I would get the job done quickly, but the only thing I had to show for it was the final result.

Most of the knowledge I’d gathered along the way inevitably faded over time — our brains just don’t retain everything.

And in IT, the same kinds of problems and situations tend to come back. When that happens, you often find yourself starting almost from scratch again.

Working with the Zettelkasten, on the other hand, means I move more slowly, but at the same time I build up:

Of course, this would matter little if I never had the chance to reuse what I’d done before — but that rarely happens. in my days, things often recur.

Today I use the Zettelkasten because it works well for me, though it’s obviously not the only possible method.

I mention it because it’s a tool that allows me to do exactly what I’ve just described.

The main thing I've learned is the value of writing. Writing is slow, but written things persist and accumulate over time. And things written in a "good way" become valuable.

Naturally, the process isn’t as ideal as it sounds.

It’s demanding, and I’d be lying if I said it doesn’t require extra effort.

Sometimes I spend a lot of time on things that seem useless, or whose value I can’t yet see — but even then, I’m gaining experience, and learning something is never a waste.

I’ll be honest: this practice often leads me to keep working on my Zettelkasten even in my free time.

I want to complete the "Zettelkasten way" of a project, even after work hours are over.

But I don’t see that as a problem — finishing a project through the Zettelkasten gives me a sense of personal satisfaction and engagement that goes beyond simple work fulfillment.

Maybe this all sounds a bit long-winded, so here’s the summary.

Yes, it’s true: time is a major factor. The Zettelkasten method isn’t "cheap" in terms of effort or time.

But I consider it an excellent investment if you truly want to learn something.

I don’t think there’s an "easy" or "efficient" way to learn deeply.

Recalling the principle of doing it whenever possible, If I only have one hour a day, I’d rather spend that hour building notes on a single article of two pages than skim an entire book in the same time and forget it two days later.

In the first case, I’m actually accumulating knowledge.

In the second, I’m just feeding an illusion.

You need to find the way to balance the learning process with the time you have available, keeping in mind that learning is demanding in any case. I think there are no shortcuts.

I can add, one of the advantages of Zettelkasten is that it is, in a way, incremental.

If at this moment I barely have time to write even a single note, and in a very rough version, I don’t give up saying I have too little time to do a complete and perfect writing regarding an activity or a learning session; instead, I just write that single rough note. Tomorrow, I’ll still have it. It's a very small progress, but it will remain a progress.

If you want to know my actual process when I work, I can describe it in broad strokes.

Alongside my usual work tools, I practically always have an Obsidian window open, on a note I call the thinking canvas.

If, while working, what I call a "situation" arises (a problem, question, reflection, task, or something I need to study), I jot it down on the canvas. When my mind starts formulating thoughts to solve anything of those tasks, the ones worth noting I quickly write on the canvas.

If a good amount of material accumulates about a single situation, I move everything to a note dedicated to that situation.

What’s written on the canvas or in the situation note can, later on, lead to the development of one or more Zettels if it’s worthwhile.

My main trick is having developed the habit of writing down my thoughts (not all of them, of course) while I work, instead of just thinking them. Once it’s written, it can be developed at any other time and accumulated later.

For me, the key is simply not making the mistake of building a system that requires a lot of energy during the pure initial capture phase of ideas.

What I found essential here is simple bullet writing.

With this method, I jot down my thoughts—in reality, just a few seconds—right while I’m working, and later I can devote more time to those worth developing into Zettels that will be useful over time.

One thing aspiring autodidacts with polymath ambitions should try is to go intentionally wide but shallow.

In practice, start with introductory material that’s easy to digest overall but cognitively loaded enough to reveal what you already know and what you don’t. For the next round, choose another introductory resource on a new topic that overlaps with those knowns and unknowns. Keep repeating, and you’ll build an intellectual map of your interests, its density reflecting your level of comprehension.

This map will highlight what you know by heart and what keeps surfacing despite your gaps—signaling its importance. The latter deserves deeper investment; it’s likely the missing trunk that would anchor your intellectual growth. Mapping first prevents wasting effort on demanding but peripheral topics.

Still, you don’t need to match experts in every field. Life’s too short for that. Forums like this let you stand on the shoulders of those who’ve already gone deep, learning from them instead of feeling inferior. You only need enough grasp to judge a topic’s relevance to you.

Thanks for that. The last three or four previous entries, above, have been very helpful to my thinking.

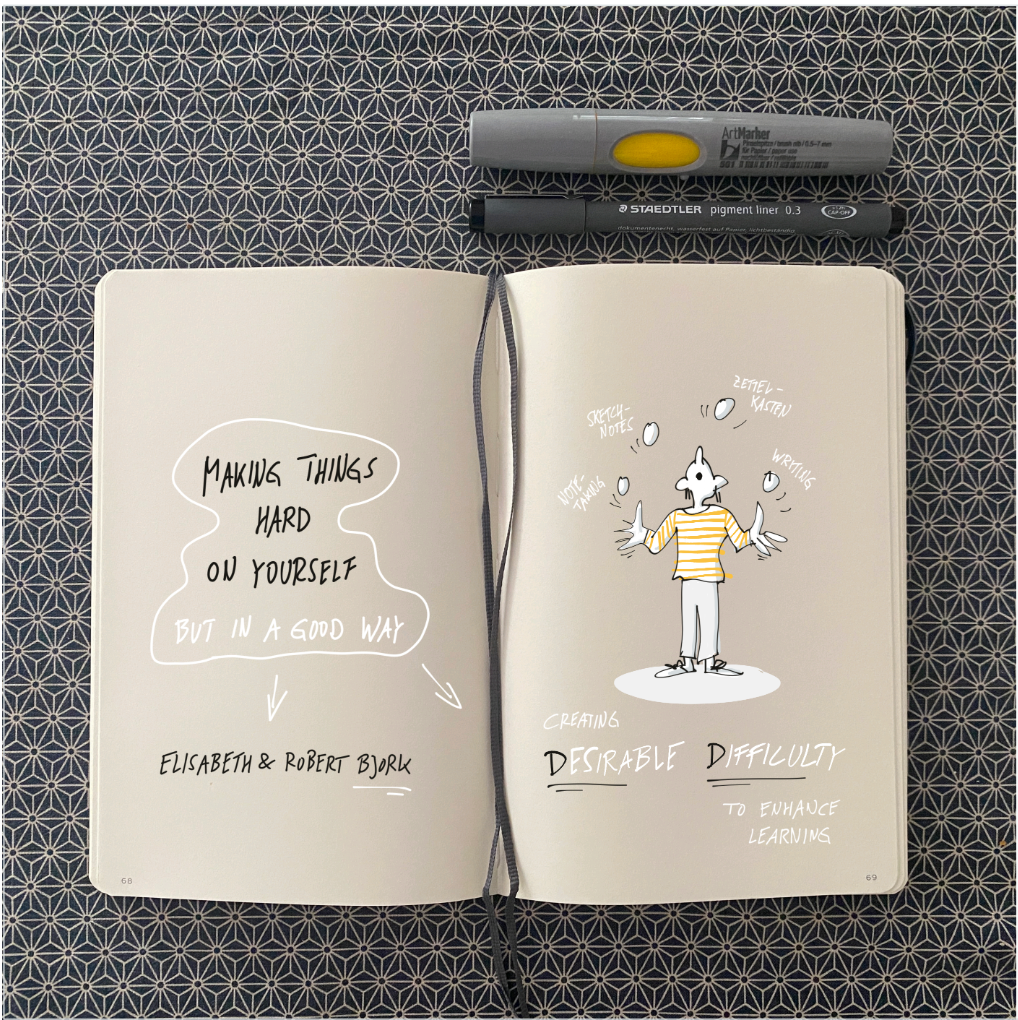

I feel a little bit awkward answering to this thread. My awkwardness is encapsulated in this picture:

(It is a troll by Christian as a response to my constant trolling and an allusion to a chapter in Nietzsche's Ecce Homo titled as said in the image)

I'd like to advertise the idea of a structured deep knowledge work practice. It is a term based on Cal Newport's Deep Work. A less high-brow term might be a "studying practice".

The basic mindset is similar as in general training. The bottleneck is typically time. If you can free an hour per day of training you can consider yourself lucky in most life circumstances. So, training efficiency is the biggest lever to improve the outcome.

When you study, all you can do is to search for good material and structure studying, so you can fully commit your mind to the task at hand. The material's content is dependent on your goals. If you are interested in general ability, you chose general skills like critical thinking, system thinking, design thinking, lateral thinking and the like. Then you dig deep into a couple of topics or even while you are also working on thinking skills.

From experience, I can say that it becomes much easier to build a reasonable expertise when you did it a couple of times. A lot of the friction comes from lack of practice.

But keep in mind that many of the forum member's main job is dependent on their expertise. So, you are basically asking bricklayers how their walls are so straight.

I am a Zettler

@iylock By developing and then cultivating throughout your life a passion for learning.

So, you're using Zettelkasten while working, stockpiling inventory in areas of interest and processing them later. That sounds useful. Thank you.

Your words are helpful to me. I could use the method of reading introductory books in each field and then choosing which ones to delve into.

Yes. Life is too short, so you have to choose which field to study. What criteria do you use to make your choice?

I like this picture because I think it conveys the situation you are in and the emotions you feel.

If time is the bottleneck, I understand that finding good materials and structuring your study are key to efficiency. So, is there a suitable way to find good materials and structure your study?

Does this mean that the answers given by forum members are in their areas of expertise?

Yes! Thank you. Do you have your own unique driving force that fosters your passion for learning?

There are multiple ways how to attack this issue depending on your goal.

Quite often the answer is yes. Especially if you are in academics the overlap of general good practices of knowledge work and your own domain is high. Philosophers, chemical engineers, historians, theologians - all have more than just basic knowledge on how to track down key sources, writing articles or reports etc.

On top: If you developed just one area of expertise, you can filter general problems through it and can provide a reasonable answer to questions that are outside of the domain.

I had one client who was an engineer and wanted to develop his own theology. Whenever he applied his engineering thinking to the challenge, the models and ideas that he developed were of ingenious simplicity and power.

I am a Zettler

Talking about me :-)

Sometimes yes and sometimes no. It depends on the topic of discussion. In some areas I can consider myself competent; in others I may be a curious beginner exploring the subject, and I might write an opinion or simply a personal impression. What happens most often, since I work in the IT field and this is a forum dedicated to Zettelkasten and, more generally, to knowledge development, is that I tend to transfer the principles of my main field of expertise (the first one) into the second one, which I’m still building day by day.

As for Zettelkasten, I think I can say that I’ve become "good" at it, even if I can’t exactly call myself an "expert".

I’ve studied it a lot, I’ve read extensively about it, I’ve practiced it quite a bit (I have around 6,000 notes), and I’ve especially built a personal model that gives me objective results. Without presumption, I believe I’ve understood it very well, and I’m able to answer many of the questions that come up.

Despite this, I don’t consider myself a top-level expert because, since it isn’t my primary field, I don’t have all the foundational studies in epistemology that other people have undertaken.

This is me today. Three years ago, I was someone who didn’t understand anything about the Zettelkasten. With consistent participation, the state changes over time.

I feel that I could write a good post about how to use the Zettelkasten in engineering (thanks to my experience in both fields), but I wouldn’t be able to do the same regarding its use for writing a very simple book. In that case, I could only write about my own opinion or impression. And I do both things :-)

Today I asked for a good book about Zettelkasten. They didn't have any. 😉

Edmund Gröpl — 100% organic thinking. Less than 5% AI-generated ideas.

The method you provided is helpful to me. Until now, I'd been diving into research without a clear goal in mind. After reading your method, I realized why I fell into the rabbit hole: the lack of clear goal setting.

I understand what you mean, because I've used the mental models and problem-solving methods I developed in my field to creatively solve problems in other fields or develop my own ideas. Thanks to you, I feel like I've gained a vague sense of direction for my future.

It reminds me that becoming an expert in one field can be helpful when learning other areas. It's important to integrate your existing knowledge with the new knowledge you're learning.

As for Zettelkasten, it's worth the nickname.

If you are young and have time, it is better to choose fields that are more difficult to master and more fundamental. In science, it would be physics, for example. Through it, you learn mathematical ability and logical thinking, as well as how to find consistency between reality and theory via the scientific process. Mathematical ability is also useful for understanding derivative fields such as chemistry, engineering, and others. Acquiring such general-purpose disciplines in this way allows you to obtain transferable skills. This tendency can be seen in the fact that many engineers currently working at the cutting edge of AI research have backgrounds in theoretical physics. Statistics, too, would be useful widely, e.g., even in the social sciences.

Even if you are not choosing a major at university, the aforementioned map of knowledge can help you identify where the gaps in your understanding lie.

For example, recently I am interested in the loss of meaning in modern society. I have been tracing how Western civilization has come to terms with Nietzsche’s declaration that “God is dead” and his concepts of nihilism and ressentiment. In that process, I encountered John Gray’s view that New Atheism, progressivism, and scientism are all dragged along by a monotheistic worldview, and you learned that even the American right-wing’s neo-reactionary movement has, at its root, a desire to overcome Nietzschean nihilism.

The fact that countless arrows on the map of knowledge point toward Nietzsche indicates that there may be an unseen trunk there. Long before me, predecessors who excelled at thinking had already put it into words. The deeper I come to know it, the stronger the trunk of my own knowledge will become. I’m interested in everyday philosophy but neither like nor have the grounding for academic philosophy, especially ones before the Scientific Revolution (my science background has made me too much of a materialist). Nevertheless, by looking at the map in this way, I can see whose shoulders of giants I should probably stand on, if I so desire.

@zettelsan said:

For a more deflationary view of Nietzsche's relative (un)importance, read the chapter on him in Bertrand Russell's A History of Western Philosophy (1945). (There are many scanned copies of the book in the Internet Archive.) If you haven't read the rest of Russell's book, you may want to take a look at that too.

I think Gilles Deleuze's summary of Nietzsche's place in the Anglophone world, in the preface to the English translation of Deleuze's book Nietzsche and Philosophy (trans. Hugh Tomlinson, New York: Columbia UP, 1983), is pretty good:

Many of Nietzsche's central concerns are irrelevant in the ratio-empiricist Anglophone context (especially Anglophone America) where a different tradition of pragmatist philosophy reconstructed Western intellectual coordinates without a sharp break from the religious past. This can be seen especially in the career of John Dewey, who transitioned elegantly from a youthful Christian Hegelianism to his mature naturalistic pragmatism that was nevertheless not incompatible with his starting point: see, e.g., how he reconstructed the meaning of "God" in his later book A Common Faith (New Haven: Yale UP, 1934). This trajectory is also reflected in the history of religious innovation in the United States, where there are very liberal religious denominations wherein it's unimportant what your position on God is (e.g. Unitarian Universalism).

To tie this discussion back to the original topic: it's important to be familiar with multiple perspectives and narratives in a field such as history of philosophy. If you only know one perspective or narrative, it may seem that "countless arrows on the map of knowledge point toward Nietzsche", whereas from another perspective he is of little importance.

@Andy It is as if you specifically wrote this post to trigger me. (I am a big fan of Nietzsche)

(I am a big fan of Nietzsche)

Some counter-positions:

Another way to phrase it was that Anglo-American philosophers didn't take Nietzsche (among other continental philosophers) seriously. One could say, that the anglo-american sphere was recklessly ignorant of the problems that Nietzsche presented.

Here: Nietzsche's position was a historical-social one. That some philosopher tried to justify the Enlightened framework without Christianity doesn't mean that their work is relevant. Nietzsche didn't say that you can't try and that you can't try with admirable intellectual skill. He said that society and culture will ultimately fail.

Beware of my self-sealing position:

The chapter highlights that Nietzsche wasn't unimportant but rather repressed. Such a violent attack warrants are deeper look: Nietzsche is not irrelevant, as the repressed trauma creating a blind spot is not irrelevant, though you might lash out if somebody points at it.

I am a Zettler

@Sascha, my trolling worked!

Nietzsche is important in continental philosophy, for sure, and there are many fans of Nietzsche.

What I am warning @zettelsan against is big narratives about intellectual history like John Gray's. Terry Eagleton's criticism of Gray's book Straw Dogs that is quoted in the criticism section of the Wikipedia article on Gray seems to me to be entirely on target: "mixing nihilism and New Ageism in equal measure, Gray scoffs at the notion of progress for 150 pages before conceding that there is something to be said for anaesthetics. The enemy in his sights is not so much a straw dog as a straw man..."

Bertrand Russell is just a counterexample of an opposing big narrative, one that is probably no better than John Gray's. Russell's book should be read as a source of Russell's opinions, not as an adequately careful, comprehensive, and nuanced history of philosophy. I don't think that one person could write such an adequate history.

I mentioned John Dewey, who was criticized both by Russell and by orthodox Christian opponents, famously Reinhold Niebuhr. There are several books about the conflict between Niebuhr and Dewey, which was mostly about Niebuhr criticizing Dewey. In this horse race, I can be very clear about my bias: I am on the side of Dewey against Niebuhr.

The positive advice that I can give is that anyone doing intellectual history should keep in mind at least three of the criteria for quality in qualitative research that are taught in Qualitative Literacy by Mario Luis Small & Jessica McCrory Calarco (University of California Press, 2022): cognitive empathy (understanding how other people view the world and themselves), heterogeneity (adequately representing the diversity of perceptions, experiences, motivations, and other aspects within populations of people), and self-awareness (adequately expressing your awareness of how who you are as a researcher affects your research). Big narratives are often deficient in these qualities.

I think that Russell's chapter on Nietzsche is badly deficient in cognitive empathy for Nietzsche but is sufficiently self-aware: Russell is very clear that he is giving his idiosyncratic personal opinion about Nietzsche, not a God's-eye view. Sascha too is admirably self-aware.

EDIT, 11/22: When I spoke of "big narratives" above, I was thinking not of narratives about objective processes such as continental drift, but narratives about subjective phenomena such as "loss of meaning", "nihilism and ressentiment", "a monotheistic worldview", etc.

Thank you for pointing out the important points on how we can benefit from the forum.

I agree with your point that it's worth learning difficult, yet fundamental, foundational disciplines in other fields. Thank you.

First, let me say this: when I answered the question about how I choose what to dig into, that’s all I was doing. I wasn’t trying to make any grand claim about Nietzsche’s importance. Suppose instead of Nietzsche I had picked something more “inorganic” as my deep-dive topic, e.g., the replication crisis in science, and along the way I happened to land on p-values. Would you have insisted that I first properly study the entire history of the philosophy of statistics? Probably not.

(Also, you don’t need to worry about me getting lost in proper names. I generally dislike overly personal arguments anyway. It just so happened that, while preparing my answer to the original question, the notes that caught my eye were the ones on Nietzsche and John Gray. That’s all.)

Another thing: the fact that you dislike Nietzsche and others doesn’t give you any standing to warn someone about studying him. Even if I eventually conclude that he’s an overrated philosopher, that conclusion would only be legitimate if I had understood him well enough first, right? (And since I honestly don’t have time to go deep on Nietzsche anyway, your concern is going to turn out to be moot. LOL.)

This isn’t me lashing out because I sensed bad faith or anything. But writing all this has made me realize something: even well-meaning advice that says “true wisdom requires broadening the circle very wide” can end up sounding like “don’t even try,” and that can shrink people instead of empowering them.

Of course, if you’re going to lean on the thinking and language of past philosophers, the deeper your knowledge of philosophical history, the better. But unless someone is suffering from full-blown Dunning-Kruger, the moment they start any serious intellectual activity they quickly realize that the world contains far more knowledge than one lifetime can ever master.

So the choice is: give up because “it’s too much for me,” or recognize your own limits, figure out what you actually want to know, and do your intellectual work inside that bounded space? Even people who make intellectual activity their profession have no real choice but the latter. Most physicists are ignorant of philosophy; most philosophers are ignorant of physics. One of the main questions of the thread is this: “not having time because I have a job.” Setting realistic boundaries seems especially important there.

That said, I’m grateful that you made me aware of what “God is dead” means in an American context. You’re right in that America has historically distanced itself from Europe on questions of religion, yet for an advanced country heading toward secularism, it retains a strikingly strong religious character. That’s a fascinating new thread I can develop in my notes later.

Still, I’m not particularly interested in academic questions, academic answers, or the history of philosophy as such. I’m following this topic for very personal reasons, not because I’m trying to deliver some lofty ultimate answer to an ultimate question.

I won’t derail the original purpose of the thread by going deeper here, but what actually interests me is ordinary, everyday despair and nihilism—the kind on the street—and the possibility of overcoming it. By “ordinary” I mean the neighbor in my apartment building who died of an overdose. The owner of the piss and shit you step in or smell on your commute downtown in a U.S. city... their lives of emptiness. Or those elites who work at AI hotshots, making half a million dollars every year but realize they don’t really have anything meaningful to spend that money on. Even if America were somehow untouched by Nietzschean nihilism, and even if these people aren’t intellectual enough to understand academic philosophy, has the American philosophy you’d praise in its place actually succeeded in giving them hope?

How exactly has meaning been created for lives that fall outside the realm of highbrow academic philosophy, lives that history will forget on the edge of oblivion? That’s where my current interest lies (because my life is one of them).

@zettelsan, thank you, that was beautifully written. I loved reading it, and I'm grateful that you wrote it.

To answer your last question: I think what you're asking about is addressed by applied psychology: e.g. community psychology, psychotherapy, counseling, social work, etc. There is a huge literature in those fields that addresses meaning in life, and practitioners in those fields use that knowledge in their work with ordinary struggling people on the streets or wherever. I'm familiar with that literature too, and I can suggest readings, but if you don't have time to study it, rest assured that those issues have been addressed in those applied psychological fields, in theory and in practice.

To answer your penultimate question: Yes, John Dewey was an applied psychologist as well as a philosopher, and his writings on education during the Progressive Era in the U.S. contributed to the applied psychological fields that I mentioned in the previous paragraph. I wouldn't recommend reading him today for the practical details of applied psychology, as his works are outdated now for that purpose, but they do form part of the historical background of those fields.

Hi @iylock, here's my brief response to your thought-provoking question:

References

[1] Bjork, Elizabeth and Robert (November 2009). "Making Things Hard on Yourself, But in a Good Way: Creating Desirable Difficulties to Enhance Learning" (PDF).

[2] Bjork, E., & Bjork, R. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society, 56-64.

Edmund Gröpl — 100% organic thinking. Less than 5% AI-generated ideas.

I love your illustrations every time I see them. Thank you for your response. I'll check out the references you provided.