What are some things that we ought to know about developing ideas but aren't talking about?

Since building your zettelkasten, what are some things you've learned about developing ideas (or/and coming up with insights) that you think are not being talked about enough?

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

Do you mean not being talked about in these forums?

In my case I can't really think of anything at all. I often think that most people could benefit from knowing more about the psychology underlying these things, but that is a general observation.

@jellis, much of the talk on the forum is about the techniques of zettelkasting. This is natural as it is a welcoming place for beginners. There is some discussion on how to develop ideas. @Sascha's videos and blog posts focus on capturing insights into your zettelkasten.

@thomasteepe is another member of the forum that is interested in insight driven zettelkasting. Both here and here are current discussions.

I to am interested in this topic. There is a lot of value in sharing the why's of our work and not just the how's.

What have you learned about developing ideas?

Will Simpson

My peak cognition is behind me. One day soon, I will read my last book, write my last note, eat my last meal, and kiss my sweetie for the last time.

My Internet Home — My Now Page

My occasional book recommendations haven't been discussed, much less discussed enough, of course.

Claim: There are no non-trivial universal, content-independent methods for generating "ideas."

Otherwise there would be evidence of the valuable ideas generated.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

@ZettelDistraction

Hmmm, the evidence is all around you, in all aspects and fields of daily life. Ingenuity abounds.

And if evidence (valuable ideas) abounds, so also do the methods of generating them - even if they only involve sitting under an apple tree

@jellis, here we go.

@ZettelDistraction, I wonder if your negative claim is "evidence" or non-evidence of any proof?

Sorry, I didn't catch the implications of your book recommendations.

Is "no non-trivial" a fancy way of saying anything goes? Maybe you mistyped? Please tutor me.

Will Simpson

My peak cognition is behind me. One day soon, I will read my last book, write my last note, eat my last meal, and kiss my sweetie for the last time.

My Internet Home — My Now Page

I think that is a hard question to answer because it depends on where one is at in their knowledge work journey. An insight to one person might be an obvious connection to another. I do wish this forum itself was somehow a public zettelkasten in itself.

It's a claim, not evidence of the claim.

"No non-trivial" means nothing non-obvious or not trite, nothing that isn't rudimentary, or beyond the first things that would occur to a non expert. The further qualification is the universal generality.

The move from "non non-trivial" to "anything goes" isn't logically valid, but it's not a bad heuristic.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

The claim refers to universal methods.

How many of those ideas were generated by a non-trivial, universal subject-independent method?

If apple trees worked for every subject, I imagine that every think tank and university R&D department would have it's own apple tree, Niklaus Luhmann would have written that both he and his Zettelkasten, which (or rather whom) he considered a communication partner, would need their own apple trees--the trees would be part of the system, and eventually it would dawn on me to get one to sit under myself. Maybe that's what I should do before posting again.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

Here are some points I find intriguing.

Andrew Wiles' proof of Fermat's Last Theorem FLT is one of the Wonders of the World of Mathematics. Its story is well documented - seven years of unbelievably focused work, done in virtual secrecy.

I am asking myself if and how zettelkasten supported work could play a role in problem solving or theory building, in mathematics or elsewhere. My current guess would be that a zettelkasten dedicated to problem solving of some magnitude (not necessarily a pinnacle like FLT) would contain crucial structures that play a minor role in current discussions - I would expect elements like the following:

(Btw, if you know sources that describe Wiles' actual work habits and especially his note organisation, please share.)

Many scientists write joint papers with their colleagues, and sometimes they consider these their best work. This joint work has to be organized.

What can be said about the use of ZKs in collaborative work? Perhaps it isn't a good idea at all, since ZKs are meant for growth over years and decades, and are inherently meant for an individual author.

I am currently surprised by some of this forum's vaguely ZK-like characteristics. (I bet I am not the only one searching the forum for keywords and sometimes wishing he could add links between posts?)

The idea of public ZKs is certainly not new, but I think some discussion about it could be interesting.

Given the pivotal role of ideas in progress in general, I think the craftsmanship aspects of generating ideas are still underrepresented in discussions - how do you actually produce ideas? How do you store them in the ZK (or outside of it)? How do you develop them from a first hunch to something really useful?

Don't take things so literally; there is the option of finding a bit of humour in any serious subject - particularly when you have an emoji as a hint, since we aren't sitting face to face and reading body language.

Back atcha @GeoEng51

@jellis Are you going to express surprise or outrage or post memes to Twitter if we hit on something that hasn't been talked about enough? Just kidding.

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

Personally, I try to be open minded towards all methods that generate ""ideas"" .

In particular, I am a huge fan of some methods that are

Seriously, and again: @ZettelDistraction - What is your point? I wonder if many people would actually state that they have achieved something relevant solely with methods that are non-trivial, universal and content-independent. I find this list of restrictions fairly artificial - why not just focus on the more pragmatic question of how to generate useful ideas in a specific domain, which is often hard enough without imposing extra demands on the methods used?

I have a very vague suspicion that you are aiming at something different - perhaps that it's very hard to generate relevant ideas in a specific domain without having profound knowledge there and without using very specific tools. If I am not totally misguided in this - could you present a revised version of the claim above?

At this moment, I still think the following: Even if it is not possible to "mechanize" the entire process of generating ideas needed to solve a problem - would this mean that we should not attempt some forms of "mechanizing" where it is possible?

I would certainly not expect that this method will generate an immediate breakthrough with any given topic, but I would expect some interesting insights.

@ZettelDistraction, I find your argument that such a method would be in broad use in think tanks and universities and companies interesting. I have some vague ideas about this - perhaps many institutions rely on methods of collaboration that make such formalized methods unnecessary since group discussion provide something very similar and perhaps even superior. And the methods used by an individual are not in every case externalized to a degree that they can be transferred to other persons.

So am I.

That was it: generally speaking, one has to relax at least one of the conditions, as you just did.

This is probably true for pure mathematics, and less so for applied mathematics, where success is defined differently--still one probably needs considerable experience to identify accessible open research areas. I tried to indicate such an area in another thread, and gave a reference.

A logician, philosopher and computer scientist I know said that a mathematician would rather dig for a vein of copper ore in an inaccessible abandoned mine at the top of a mountain, than pick up gems strewn about the entrance an accessible mine at the foot of the mountain.

Right now I believe it's possible to do good work in mathematical social science, without necessarily needing the depth and background it would take to do work suitable for publishing in the Annals of Mathematics. That was true at least a decade ago, and it's still true.

Maybe my conditions weren't so ersatz after all. Not everything has numerical parameters that can be varied, but let's say that properties can be varied, even if there is no relevant notion of small.

That's fair. My skepticism seems to have been overcome.

One glaring omission: I didn't cite a single reference or offer any evidence for my skeptical claim. That's a no-no for a researcher. And that leads me back to your first question:

My larger point is that I think these methodological discussions would benefit from citation of the literature. @MartinBB hinted at this earlier. Then some of the unsaid things might become evident. Perhaps making convincing use of the relevant literature and citing it (to mention something not discussed enough) would spoil the fun.

Another question: if I am so skeptical, why bother to build a Zettelkasten at all? So far it seems to have defeated every other contender for a note-taking system. Maybe it's even more than a note-taking system. There is some social proof that it "works," though the slow traditional epistemic gatekeepers have been largely circumvented by the Internet.

Finally, some things that could be talked about, with citations--the two articles below should indicate how to adapt Luhmann's system to digital Zettelkasten. That is, instead of armchair speculation or musing about methods, check how to faithfully adapt Luhmann's paper system to digital Zettelkasten, following these references. A checklist for interaction with the system as Luhmann did with his ZK could be useful, e.g., when adding or modifying Zettels, check that the current Zettel is related to prior Zettels...

References

Johannes Schmidt. Niklas Luhmann´s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine, in: Alberto Cevolini (ed.) (2016): Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 289-311

Johannes Schmidt. Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: The Fabrication of Serendipity, in: Sociologica 12 (2018), 1 (Symposium: „Heuristics of Discovery“), 53-60

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.

Thanks for refreshing my view of this story. In an interview on NOVA, Andrew told of using one of our favorite non-trivial all-purpose tools - going for a walk.

NOVA: Usually people work in groups and use each other for support. What did you do when you hit a brick wall?

AW: When I got stuck and I didn't know what to do next, I would go out for a walk. I'd often walk down by the lake. Walking has a very good effect in that you're in this state of relaxation, but at the same time you're allowing the sub-conscious to work on you. And often if you have one particular thing buzzing in your mind then you don't need anything to write with or any desk. I'd always have a pencil and paper ready and, if I really had an idea, I'd sit down at a bench and I'd start scribbling away.

I like this analogy. It reminds me of David Allen's 10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000 50,000 foot view. The Stoics also loved to zoom in and out, viewing the world.

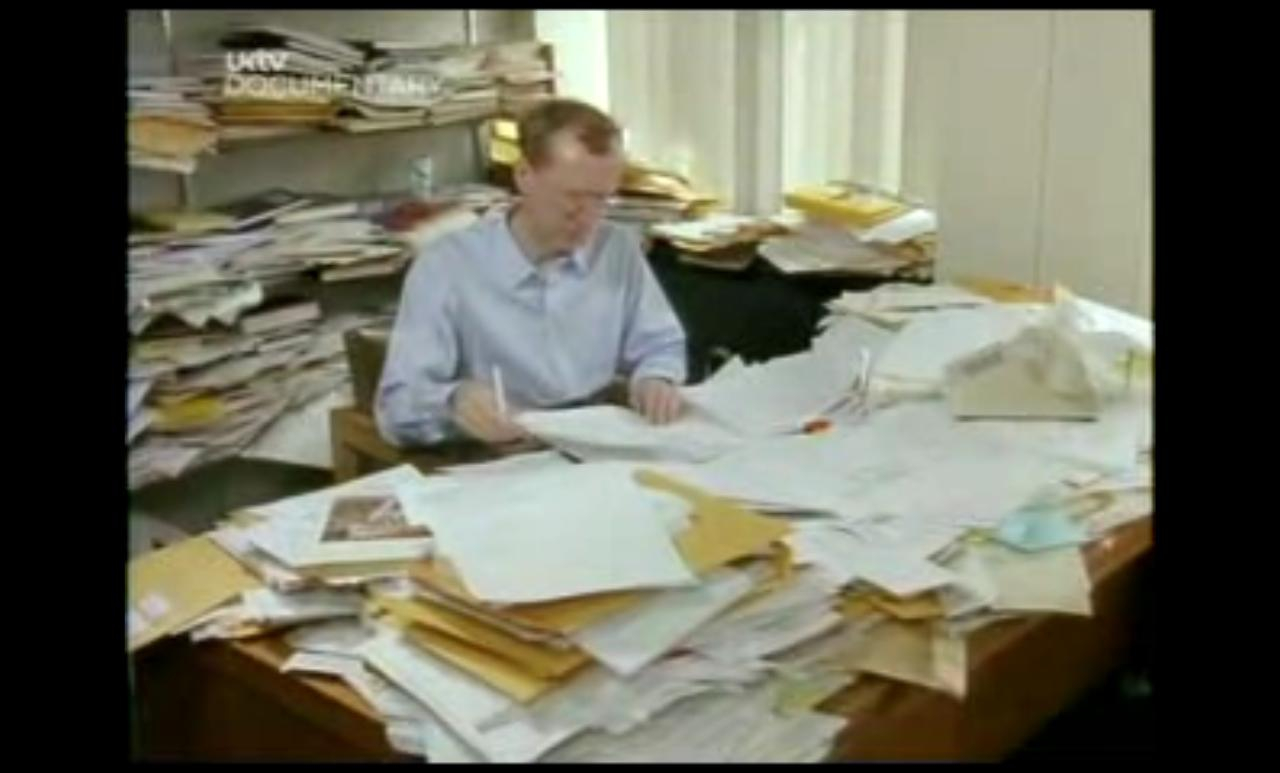

I came across this 1996 photo of Andrew Wiles at his desk.

Source

I'm with you. A collaborative zettelkasten is an idea that could only work with a magical mix of participants and then only with strict constraints on a long timeline.

The craft of zettelkasting. The mindset of craftsmanship is near and dear. How do we describe the craft of zettelkasting? In part, it is the craft of writing, and the craft of writing is the craft of editing. With incremental editing and lots of time, an idea will grow from a seedling to a giant oak.

Time scale along with an altitude scale is needed for clarity. The balance of these needs varies with the relevancy of an idea. As apprentice craftsmen, in the beginning, our time scale and the altitudinal view are short and small. In the beginning, being a little shortsighted and inpatient is natural. Work on longer time scales tends to be more significant and more impactful. Skills build quickly after the period of apprenticeship. With time we can compound our knowledge with sustained effort, much like in weight training, hitting the gym regularly. Journeyman and master craftsmen know that a sustained effort over time beats chance and luck 99 times out of 100.

Here is an actionable tip to help in the craft of ideation. When working on a fledgling idea and gaining traction, circling it, seeing it from new sides, suddenly, mid-sentence, quit for the night! Leave the excitement hanging. Go for an evening stroll, get a good night's sleep. I guarantee that in the morning, you will be chomping at the bit to get back in the ring with the idea with a new clarity horizon.

Will Simpson

My peak cognition is behind me. One day soon, I will read my last book, write my last note, eat my last meal, and kiss my sweetie for the last time.

My Internet Home — My Now Page

You got me.

In my previous overblown post, I suggested doing something that probably has already been done in this forum or elsewhere: write out a step-by-step interpretation in a digital Zettelkasten of Luhmann's process with his physical Zettelkasten, following

Schmidt, J. F. (2018). Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: The Fabrication of Serendipity. Sociologica, 12(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/8350.

and with more detail in

Niklas Luhmann´s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine, in: Alberto Cevolini (ed.) (2016): Forgetting Machines. Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 289-311.

According to Schmidt, Luhmann used his ZK as a "surprise generator...by combining a specific system of organization and method of card integration with specific rules of numbering, an internal system of references, and a comprehensive keyword index."

There seems to be enough in these references (not to mention others) for a concise, straightforward step-by-step interpretation in a digital ZK of Luhmann's "system of organization and card integration" together with appropriately interpreted rules for interaction with the ZK--enough to write down a checklist to ensure adherence to the process.

But I can't promise the rhapsodic eloquence of some other forum contributors...

GitHub. Erdős #2. Problems worthy of attack / prove their worth by hitting back. -- Piet Hein. Alter ego: Erel Dogg (not the first). CC BY-SA 4.0.