Isn't a zettel actually a module? And about structure notes.

Isn't a zettel actually a module?

I thought about structure notes.

@Sascha said that structure notes are notes that describe the relationships between zettels. here. So he said that it can be described in various ways other than TOC format. here.

However, for me who only uses plain text for Zettelkasten (and doesn't use markdown), the format of structure notes can only be TOC and tables.

The biggest problem when expressing structure notes as TOC or tables is that the relationships between zettels are not clearly revealed. In other words, a hierarchy is created, but the context is only implicitly revealed.

To solve this, I wrote the link context by expressing the structure note in the form of text, but the readability was poor. Also, when using the link context, it was difficult to check what the original meaning of the original zettel was when it was taken out of context.

Then I thought of modules in programming.

If structure notes are notes that describe the relationship between zettels, then they are in fact modules.

Also, if you think about modules in programming, content notes themselves are modules. This is because even a single zettel divided according to the atomicity principle can function and can be called from another zettel.

From a modular perspective, both content notes and structure notes seem to ultimately have the same goal.

Many people think of zettels as Lego blocks, but this is different from modules. Modules are parts that have independent functions. On the other hand, Lego blocks are not functional units. They are simply highly modular parts.

So I thought that zettels were in fact modules. (zettel is a general term for content notes and structure notes.)

If you look at it that way, I think it would be helpful to write structure notes from the perspective of actually creating modules. So, a structure note that is organized only in TOC for easy finding may not be a module.

What do you think?

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

@iylock I’d love to hear more about how you implement the “module” idea practically. Do you add internal linking syntax? Do you write mini-descriptions for each link? In the world of plain text, these little design questions matter a lot!

Your analogy to programming modules is compelling — especially the emphasis on function, not just form.

In plain text, I’ve tried to address this by carefully phrasing section headings or anchor lines as functionally meaningful prompts, rather than just categories, but I do like the faster way to linking digitally, besides knowing that the slow way lasts longer.

No. I just got this concept clear today. As you said, all of this is really important in a plain text environment. (I'm even using a plain text editor app that doesn't even indent.)

After a lot of trial and error, the current idea is to write the structure note itself as a content note.

Simply clustering the zettel or making it a TOC for structure didn't work for me. This only worked for me in the top-level structure note.

I would like to get help from the many experts in this forum to solve this problem.

@iylock, sorry that I didn't come up with a solution right away. I see that the main issue is the lack of clarity and relational context when using structure notes in plain text. As far as I connect to your problem, in a first instance I would suggest a small plain text format that records three things:

This means that the structure note does not look like a loose table of contents, but more like a comprehensible ‘connector’ that can still be understood five+ years from now.

I would classify that as a useable content note which structures thoughts, themes oder even idea complexes in an accessible way - and you will be flexible to dive into many directions.

I was thinking about my analog Zettelkasten, which is written in plain text with pen, pencil, type writer, what was at hand at the appropriate time. That would be the same setting as only writing in plain text in a digital environment nowadays.

An atomic Zettel – by definition – is not a module. Atomicity means it contains one thought, one idea, stripped of broader context or structure. It's meant to be portable and re-usable across different thematic or structural notes.

A module, on the other hand, is a functional unit, something that achieves or enables a task in a larger system. In that sense, a Zettel only becomes part of a module when:

So, no, an atomic note isn't a module.

But a well-crafted structure note can be a module—especially when it connects several atomic notes into a functional context, making the relationships and usage clear.

This difference enables us to treat structure notes like functional modules: they bridge the gap between raw (and polished) idea (Zettel) and purposeful knowledge architecture (system).

The concept of structured notes as programming modules is quite intriguing.

An individual atomic note is not a module. Think of it more as a sturcture note is a class made up of modules (functions) of atomic notes.

Here is an example.

Explanation:

This is a structural note I call a thinking canvas. It has a one-sentence summary labeled " Subatomic, " followed by a couple of writing prompts and the first module, #Philosophy, which lists atomic notes along with notes and contextual summaries of the linked atomic notes. Then, the next module, #Humor, and so on. All the modules are in service of the class, "Writing."

Writing Thinking Canvas

---

UUID: ›[[202407201743]]

cdate: 07-20-2024 05:43 PM

tags: #thinking_canvas #writing

---

Writing Thinking Canvas

Subatomic: This thinking canvas aims to gather ideas about writing in general.

Write a Subatomic description for each section.

What argument of position can I develop with this note that I can write about?

Get this in front of my eyes when I start writing.

Philosophy

The blog post should be formulated and written to search for a connection to my tribe.

Writing more concisely by using conjunctive words between ideas.

Humor

Adding humor to my writing would make it more exciting.

An example of smart humor with a math twist.

Will Simpson

My peak cognition is behind me. One day soon, I will read my last book, write my last note, eat my last meal, and kiss my sweetie for the last time.

My Internet Home — My Now Page

Oh, you can think of it that way. Yes, according to you, the atomic Zettel is not a module.

The reason I thought of Atomic Zettel as a module is

1. In programming, a module can only have one function.

2. Atomic Zettel is an idea in itself, so I thought it could perform one function.

3. In a modular synthesizer, each module seemed to be like looking at Atomic Zettel. Each module performs only one function. here

I think there was a difference of opinion on whether to view the idea itself as a function or not. From a programming perspective, I thought Atomic Zettel was a module because it can be used like a module in programming.

However, I don't think it matters whether Atomic Zettel is a module or not. I think it's more important to view structure notes as modules. If you view structure notes from a module perspective, the way you write them changes completely. So I don't think it matters much in practical terms whether Atomic Zettel is a module or not.

Anyway, I think you've been thinking quite a bit about the Zettelkasten from a module perspective.

Thank you for your advice. I'd like to know more about what you advised. Can you give me a specific example?

I'd like to know more about what you advised. Can you give me a specific example?

Your Subatomic description seems to be a reference to @Martin 's "Function of the structure note (What is it for?)"

I like that you call the structure note a thinking canvas. And I like that you give a concrete example.

We could roll with your definition of 'atomicity' here, but for the conclusion "the definition of an atomic Zettel conflicts with 'being a module'", you need to provide missing pieces of an argument. E.g. delineate a definition of 'module', and then how these do contradict each other.

(Spoilers: I would argue for the opposite position, but I want to see your actual argument first )

)

Kudos for going plain plain text! I would like to think that the 3-bullet-list above with a bit of text, followed by a link, would work in a non-Markdown Zettelkasten just as well. Markdown is just an extra that can be nice to have. But you can also Would love to see a picture of what you see on your screen one day, though!

Would love to see a picture of what you see on your screen one day, though!

e m p h a s i z ewith non-breaking spaces, orALL CAPS, so you should be goodNow in programming, the term "module" can be used for different partitions (I've seen all of these):

This echoes the abstract "compound unit", the combination of smaller units, by means of abstraction.

Again, cf. my post on idea--idea relationships: https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/2646/more-programmer-nonsense-re-atomicity-writing-and-thinking

"Module" as a black box

The "black box" is a visual metaphor. It is a way to express the unifying principle of programming: treating (compound or simple) units of the program at the face-value of their abstraction, and combining them yourself.

A black box is characterized by:

White box ZK

In a Zettelkasten, like in a fully open source program, you can always look "inside" and turn each thing into a 'white box' where the inner mechanics are known.

The black-box-iness comes into play when you decide not to look inside, and treat what you encounter at face-value.

The title of a note becomes the first interface between human and Zettelkasten.

With a good title as the "module API", that should do the trick to roll with the metaphor here. "Application Programming Interface" doesn't make sense literally, because nothing's programmed, except (metaphorically) you, and your path through the notes, as you interpret what you see. (A different interface, Human--Machine Interface, would be more correct here, but also not convey the modularity idea.)

Composing

If you stick to ideas of functional composition:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Function_composition

Take a Zettel that links to another,

A→B, and that can link to yet another,B→C, so via transitivity, you have a connection fromA→C, albeit indirect.Modeling as composing functions

fandg, you'd end up withf‧gwheref(A)=B, andg(B)=C,fbeing the first link,gthe second.You can now characterize the connections if you want;

fandgcould be placeholders for a generic "link to", you try to come up with an algebra of connections, wherefmeans "refutes" andgmeans "is backed up by".Then you can say that yes, you can reach

CfromAviaB, the arrowA→C, labeledf‧g, is neither "refutes" or "provides evidence for". It would need to become a variant of "is in conflict with" or some such, combining both "A refutes B" and "B is backed up by C", so that the resulting "A is in conflict with C" holds.@Andy will sure have a couple of taxonomies at hand for this!

So far, I've seen no point in prohibiting any sort of connections, like enforcing a rule "only structure notes may link to other structure notes". I've also found no benefit in doing this kind of formal analysis

In the end, it's all about ideas, and ideas as 'functional units' can be large, small, simple, complex, puzzling, or self-evident, among other things.

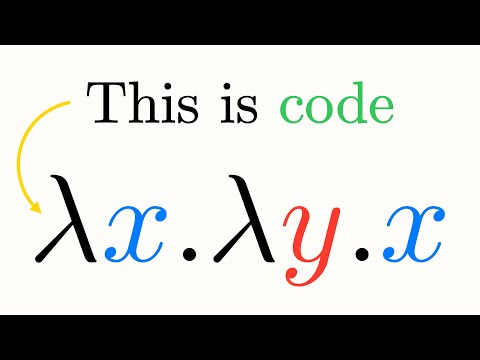

f‧gapplied tox, orf(g(x)), behaves just the same as the named functionh(x)that is the composition. It doesn't matter that there's more functions underneath, or that a function is 'composed' of others or otherwise indivisible. It's a function nevertheless, and by virtue of being a function, it provides utility.-- To talk about indivisibility, it makes more sense to apply Lambda calculus than mere function composition, because you can decompose any mathematical function into another if needed by making the term more complex while maintaining an equivalence relation during that transformation.

Where everything's expressible by

λ, it turns out, well, that everything's expressible byλ, including combinations of lambda abstractions. You do away with 'primitives' like numbers, and instead compose functions of functions that compose functions, including functions that start a chain of recursive definitions with an empty element of sorts, one that's indivisible by definition:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_encoding#Church_numerals

In a complex Zettelkasten (or any network of notes), you would have a 'leaf' note that doesn't link anywhere else, being the terminating or 'zero' element. Incoming links from any possible direction form paths, where any path itself could be encoded

f‧g‧h‧...‧zor whatever else you like, and then just like you can namef(g(x))itselfh(x), this path can be reified as a Zettel itself for more convenient access.A path through the web of your notes, 'snapshotted' into a note itself.

Or: a module, created from smaller modules, offering a simpler interface.

Author at Zettelkasten.de • https://christiantietze.de/

@ctietze TLDR is not the appropriate answer to this thoughtful consideration. I think your background in programming brings a very clear and function-oriented notion of what a module is. In computer science, a module often implies a coherent, encapsulated, and functionally complete unit — something you can insert and expect a certain behavior from.

But across disciplines, “module” doesn’t always carry that same precision. In other sciences — say, biology, education, or even philosophy (Leibniz’s monads come to mind!) — “module” might refer to something more conceptual, more permeable, or even more abstractly integrated. It’s a useful metaphor, but one that shifts meaning depending on context.

So in that sense, calling a Zettel a “module” might work metaphorically, but it also risks smuggling in expectations (like internal completeness or functional closure) that Zettel aren’t really meant to fulfill. They're more like semantic quarks — minimal, combinable, but not very useful alone.

That said, I really appreciate your take — it helps sharpen where those disciplinary metaphors align and where they tug in different directions.

To fuel the argumentative furore, I give you the following framework conditions:

An atomic Zettel — by its very definition — is not a module. Atomicity means that the note captures a single, discrete idea, entirely independent of its potential applications. It is intentionally stripped of broader contextual framing, methodological scaffolding, or hierarchical structuring. This deliberate minimalism is what allows atomic Zettel to be fluid, re-usable, and combinable across various clusters of thought.

In contrast, a module implies a pre-configured, self-contained unit with a 'specific' function within a larger structure. It presupposes context, boundaries, and a degree of internal coherence aimed at integration — not transformation.

The strength of the Zettelkasten lies precisely in this anti-modular quality of its atomic notes. They are not designed to fit a system from the outset, but to participate in emergent systems of thought as the network of notes grows. This fosters not only originality but also serendipitous recombination — a dynamic impossible to replicate with modular design.

Having said this, here comes a final thought: Every zettelnaut has its own right to his/her kingdom. What ever works in your Zettelkasten is the right thing for you. More important than overthinking the method is writing and thinking and linking within your Zettelkasten framework.

I am always fascinated by the computer programming analogies this group uses! I am a physician and theologian with no computer background so most of the time I'm either totally lost and/or intrigued.

I use a digital version of the analogue ZK which I've created on my Google drive ... I wonder, are there other non-computer "lurkers" in this community?

I agree; this comes out in most of the discussions about what constitutes a zettel or a Zettelkasten Many times, we can happily agree to disagree, while still learning from one another.

Many times, we can happily agree to disagree, while still learning from one another.

@ctietze: Epic comment! I love it.

@ctietze said:

Instead of the API metaphor, I've often thought that addressability (as in databases) is the more literal concept that applies to a Zettel.

@iylock: Check out the other discussion with ASCII diagrams that @ctietze mentioned above. I thought of the same discussion when I read your original post above.

@Martin said:

I like what you say here about an ideal polarity between two extremes of modular and anti-modular. However, a less extreme conception of module could imply (modifying your words) "a configurable unit with a range of specific functions within a larger structure". Many words and phrases in natural language may be modular this way: there is some flexibility in how they can be connected, but not infinite context-free flexibility. Atomic Zettels tend to be more like such modularity of natural language, in my experience, and less like your ideal anti-modular Zettel that is "entirely independent of its potential applications".

Modularity becomes especially apparent in my note system whenever I use a semantic schema to classify Zettels by discursive function, which makes explicit the "specific functions" of Zettels and shows how each classified Zettel is a module in a system very much like your extreme modular ideal. Not all of my Zettels are classified in this way, so I also have Zettels that are closer to your anti-modular ideal.

Sometimes I sit down and intentionally write modular notes. Sometimes what I write is not intentionally modular. It depends on what I am trying to do. That last sentence may be my answer to the question, "Isn't a zettel actually a module?"

In general, whether or not one classifies one's Zettels with some kind of schema that explicitly modularizes them, I bet some centers of modular order will eventually emerge naturally. As Luhmann said: