The Iceberg Theory of the Zettelkasten Method — Exploring the Depths

The Iceberg Theory of the Zettelkasten Method — Exploring the Depths • Zettelkasten Method

The Iceberg Theory of the Zettelkasten Method — Exploring the Depths • Zettelkasten Method

The realisation that linked notes are more useful than unlinked notes should be the start of your journey into the depths.

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

Very good post, @Sascha! I remember that you talked about some of this in an earlier discussion where I connected this analogy of "exploring the depths" to the concept of depth therapy. The hierarchical model of constructs in coherence therapy (previously called depth-oriented brief therapy) is another thinking tool (or model or framework) that uses the depth analogy. The Wikipedia section on that model also links to Logic-based therapy § Higher order premises.

The ability to apply a semi-formal model of arguments (and critical questions associated with certain types of arguments) to one's note system or personal knowledge base is a fundamental thinking tool or skill. You know you are working at the deeper levels when you can use such tools or skills to uncover deeper (or higher-order) premises or assumptions or purposes or meanings or causes that you wouldn't have uncovered if you had worked at a more superficial level. As Christian mentioned in his comment, depth is not always needed. But it's good to practice the requisite depth skills so that you can go as deep as necessary when it's necessary.

A relevant hierarchy of categories on English Wikipedia: Category:Thought → Category:Critical thinking → Category:Critical thinking skills → Category:Inquiry → Category:Problem solving → Category:Problem structuring methods

Excellent point!

Author at Zettelkasten.de • https://christiantietze.de/

Wow! This is a really good and deep post.

I really feel like going deeper (both in processing ideas and understanding the Zettelkasten method) is what makes the difference.

Thanks @Sascha for writing this post :-)

Creative work doesn’t play by conventional rules · Author at eljardindegestalt.com

Thanks very much for this writing. It contains very important points.

I've already captured some of them on my own during these months, having to read and think on a lot of fragmented sources. This article is a map that retrieve them in a systematic way.

For your thinking tools in your Zettelkasten, like the one on "The modelled object inherits the properties of the model", when do you actually make use of the Zettel?

I understand the use in representing the idea in a Zettel, but would you ever actually use the note in a specific work flow?

When I think of a toolbox, and thinking tools in it, I think of an active schema you might copy/paste etc. but in the case of your model note, it seems like a fairly static thing, and less of a "tool" and more of just a general idea.

Zettler

Level Up ⛩

I am reminded of the importance of mindset while engaging in zettelkasting. Your post is encouraging me to practice, practice, practice.

I love your framing of thinking tools not as objects but instead as processes.

Will Simpson

My peak cognition is behind me. One day soon, I will read my last book, write my last note, eat my last meal, and kiss my sweetie for the last time.

My Internet Home — My Now Page

I've been trying to improve my thinking abilities for some time now. Read tons of books but only found one effective one (Meadows'), other than that they are all talking about nonsense and are impractical.

"Thinking tools" boils down to two concepts I guess: mental lenses and running the math. To re-discover what's at hand, what mental lenses I can apply and what happens when I "run the math" between the two objects of attention (I call it that way but it is basically the same mentality with the first note you shared.) The rest is to what extent you decompose the bulk.

Selen. Psychology freak.

“You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.”

― Ursula K. Le Guin

@c4lvorias said:

Keep learning. I can't imagine how one book on the topic could be sufficient. If someone asked me to recommend one book that would cover all the thinking skills one might need, I wouldn't be able to do it.

I didn't really understand why you concluded that I don't read enough. Appreciate concrete advice like resource etc.

Selen. Psychology freak.

“You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.”

― Ursula K. Le Guin

Thanks!

I bet you like the deeper material that I hopefully have time to develop. Your associations are very similar to mine.

This is an interesting decision that I think is hard to explain and should be learned in real practice. This is one of the several reasons why the Zettelkasten Method keeps being elusive, if you don't do anything with it that is truly important to you.

This is a classic on the problem of needing proper learning material and not just textbook stuff: Argenta M. Price, Candice J. Kim, Eric W. Burkholder, Amy V. Fritz, and Carl E. Wieman (2021): A Detailed Characterization of the Expert Problem-Solving Process in Science and Engineering: Guidance for Teaching and Assessment, CBE—Life Sciences Education 3, 2021, Vol. 20, S. ar43.

Thanks!

I don't view the above as a thinking tool. Quoting myself, "The above (...) is more or less part of my self-developed instruction manual for my thinking toolbox. Here, it is a warning, similar to the warning on a circular saw, that it should never be left plugged in."

So, for me, it is (or should be) standard practice, when I use models out of my toolbox.

Then you share my way of thinking. The actual tools themselves are templates, checklists etc.

You are right. But the value of the note doesn't just lay in its isolated existence. This note is part of lines of thoughts that I might continue. My generating this note is an act of thinking itself, which happens to be within my Zettelkasten. It also forms as a reminder or could be the substance for a checklist (e.g. copypasta each time you use a model template).

Yes! Many thinking tools are just process starters.

Another book that I like: Antifragile by Nassim Taleb.

I share your opinion that many books don't give you thinking tools in such a direct and clear-cut way as "Thinking in Systems". But you get much value out of many books by applying their principles and methods.

An example is the way CrossFit thinks about fitness. I developed quite some tools by bringing together the CrossFit-way of fitness and other concepts/methods. But in itself, Crossfit doesn't provide the tools themselves.:)

I think you are correct.

This is a cultural misunderstanding. @Andy doesn't imply such things. A translation of what he wrote could be something as an encouragement:

@Andy doesn't imply such things. A translation of what he wrote could be something as an encouragement:

"Keep reading! There is hope out there."

(My Turkish wife and me have this exact misunderstanding regularly)

I am a Zettler

@Sascha said:

Sascha is right: I would not imply that somebody doesn't read enough, except insofar as everybody doesn't read enough, which is equally true of me! And I don't know enough about what you consider to be nonsense or impractical to be able to make recommendations, so I can only encourage you to keep reading.

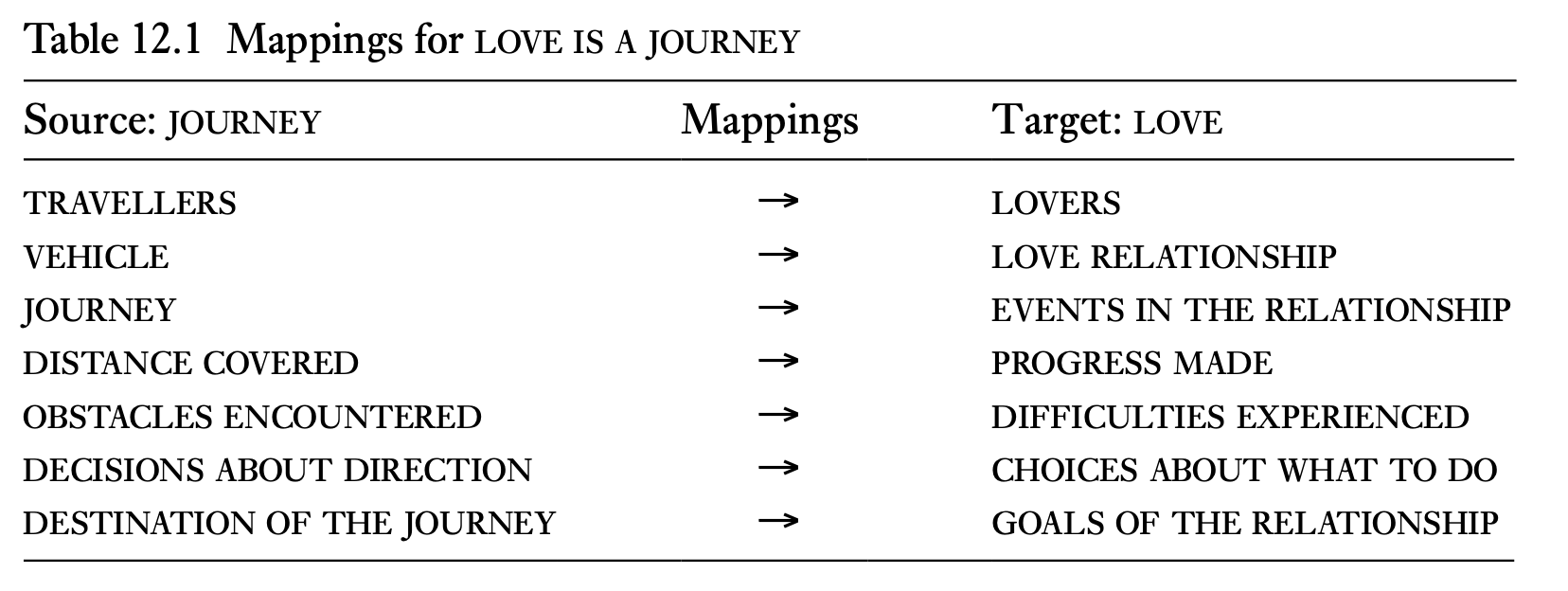

This reminds me of mappings in conceptual metaphor theory by Lakoff and Johnson. But, I'm not sure if @Sascha would agree. Let me know if you don't!

An example mapping from Vyvyan Evans's Cognitive Linguistics: A Complete Guide (2019):

It seems like you find solid "sources" like the Iceberg and then you find a lot of target domains that can map onto it (mapping being "running the math" I think).

I also thought I'd point out this literature if others hadn't encountered it before.

Could you compress any given content in a Zettelkasten down to either a tool or reasons/descriptions for the existence of a tool?

I really like the toolbox metaphor because it gets at the heart of knowledge work, and really the point of any university class or knowledge in general, to improve the quality of decisions and act; so much in the knowledge work space is surface level concerns that your iceberg model expresses clearly.

Zettler

@rwrobinson said:

This is interesting, @rwrobinson. If I may give my opinion: Sascha's iceberg model is a metaphor or analogy. So the iceberg model here does seem to be what Lakoff and Johnson call a conceptual metaphor. Wikipedia says: "Conceptual metaphors typically employ a more abstract concept as target and a more concrete or physical concept as their source." That is true of the iceberg model.

However, whether Lakoff and Johnson's conceptual metaphor theory is the best explanation is questionable. As Wikipedia again says: "While it is generally agreed that metaphors form an important part of human verbal conceptualization, there is little support for the more specific claims that are relevant to this particular theory of metaphor comprehension."1 I don't know what Vyvyan Evans's book that you cited has to say about that.

Furthermore, notice that not all of the models that Sascha mentioned are such conceptual metaphors. His model of the value-giving properties of knowledge is just a set of categories or criteria. And his thinking tool of formalizing argumentation is almost the opposite of a conceptual metaphor: it takes information that is relatively more concrete and analyzes it with a framework that is relatively more abstract.

In general, what we call models or frameworks do involve some kind of mapping, but the mapping is not necessarily metaphorical or analogical. Sometimes it is categorizing, etc. Different kinds of models have different structures.

Because the iceberg model is metaphorical, it can have different targets. For example, it can be a metaphor for:

No doubt, there must be more, or better ways to state these targets. One word that may tie them all together is systematization: the deeper levels are more systematized. For example, our behaviors don't just happen; they happen because they have systemic causes.

Wikipedia's reference is: Holyoak, Keith J.; Stamenković, Dušan (2018). "Metaphor comprehension: a critical review of theories and evidence". Psychological Bulletin. 144(6): 641–671. ↩︎

I’m glad you did!

I appreciated you calling my attention back to the non-iceberg examples. I agree these are not able to be connected to conceptual metaphor well. It also made me think through if I really understood these other two ideas.

Lastly, I’m thankful for the reference you cited from the Wikipedia article. I’m definitely interested in that review of this literature.

@Sascha : Thank you for these amazing insights about thinking tools:

Now I've learned that I use books as my thinking tools. My use of Zettelkasten can be explained by applying 5 thinking tools (5 books) to personal knowledge management:

https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/comment/19964/#Comment_19964

Edmund Gröpl — 100% organic thinking. Less than 5% AI-generated ideas.

@Sascha Thank you for putting these thoughts together. I enjoyed reading them and all the comments.

I want to discuss the first note that you shared with us (# 201705061036) - not to "nitpick" it, but to explore what it might mean in the setting in which I work.

I am a geotechnical engineer, that is, an engineer that works primarily with rock and soil. Unlike normal engineered materials like concrete, steel and even wood (to some extent), which have fairly predictable properties, rock and soil are natural materials that are highly variable in their engineering properties and hardly predictable. The high level of uncertainty is something that geotechnical engineers learn to recognize and "work" with.

That doesn't stop us from creating numerical models to help us assess how a building will settle or whether a footing or excavated slope or tunnel will collapse. The more complicated the problem, the more we like to analyze it.

You can appreciate that even after intensive investigation of ground conditions and related laboratory testing, we know very little about the actual ground we wish to disturb. If we dig a deep excavation, how much support is needed to keep the walls from collapsing. If we excavate a tunnel, what kind of support is required to hold back the forces applied by both the ground and the groundwater?

We have a saying in our field: "All numerical models are wrong; some are useful".

This brings me to your note:

>

>

Here is how I understand this concept applies to the work I do:

Reflecting on your two points above, this modelling approach allows us to:

a. On the up side, explore what conditions or properties might be important in determining how the ground at our site responds to changes imposed by the proposed project. The modelling thus serves to augment our thinking about the problem and might reveal ground conditions or properties with impacts we hadn't thought of.

b. On the down side, misrepresent actual ground conditions and end up with a design that is too optimistic (which could be unsafe) or too pessimistic (which may introduce high costs or construction complexity).

Apologies for going on so long, but I had a moment of intense insight and empathy for your zettel and thought I'd reflect on it.

I really enjoyed this post as well as the earlier discussion where @Andy connected the analogy of "exploring the depths" to the concept of depth therapy.

I shared this concept of depth therapy, specifically Coherence therapy, with a friend who's studying counseling and who suggested to also check out Gestalt therapy. I thought I'd share how I see these all connect.

In Gestalt therapy, depth is achieved via examination of one's relationships to others.

In Coherence therapy, depth is achieved via examination of one's own schemas.

In Zettelkasten, depth is achieved via improving the quality of one's thinking.

@dylanjr: The creators of coherence therapy (Bruce Ecker, Robin Ticic, Laurel Hulley) wrote a book titled Unlocking the Emotional Brain (2nd edition, Routledge, 2024) about their theory of psychological change, and in the book they mention how their theory applies to Gestalt therapy and some other brands of psychotherapy. In practice, Gestalt therapy and coherence therapy can be very similar, as both are "experiential" therapies, and there is nothing that would stop therapists from combining techniques from both. It's not quite right to say that "depth is achieved via examination of one's own schemas" in coherence therapy, because that makes it sound like it is just about self-analysis, whereas in fact the process requires experiencing just like in Gestalt therapy.

The thought just occurred to me that from the perspective of experiential therapies, the term "thinking tools" is not ideal for the deepest layer of the iceberg framework of Zettelkasten method, because the tools that we could use are not necessarily only about thinking but also about acting and experimenting in a way that changes our implicit knowledge. "Thinking" is a part of it but not the only part.

Nice, thanks for sharing this. I definitely just skimmed the wikipedia pages before making my comment, but I think what you said about both being "experiential" therapies adds to the comparison with the Zettelkasten Method. Like you said, thinking is only one part of this.