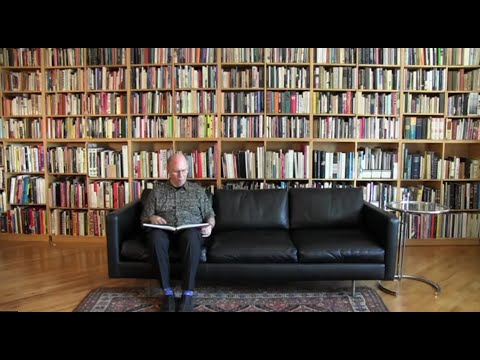

Victor Margolin's zettelkasten process for note taking and writing

It's not as refined or as compartmentalized as Niklas Luhmann's process, but art historian Victor Margolin broadly outlines his note taking and writing process in reasonable detail in this excellent three minute video. (This may be one of the shortest and best produced encapsulations of these reading/note taking/writing methods I've ever seen.)

Though he indicates it was a "process [he] developed", it is broadly similar to that of the influential "historical method" laid out by Ernst Bernheim and later Seignobos/Langlois in the late 1800s.

Victor Margolin's note taking and writing process

- Collecting materials and bibliographies in files based on categories (for chapters)

- Reads material, excerpts/note making on 5 x 7" note cards

- Generally with a title (based on visual in video)

- excerpts have page number references (much like literature notes, the refinement linking and outlining happens separately later in his mapping and writing processes)

- filed in a box with tabbed index cards by chapter number with name

- video indicates that he does write on both sides of cards breaking the usual rule to write only on one side

- Uses large pad of newsprint (roughly 18" x 24" based on visualization) to map out each chapter in visual form using his cards in a non-linear way. Out of the diagrams and clusters he creates a linear narrative form.

- Tapes diagrams to wall

- Writes in text editor on computer as he references the index cards and the visual map.

I've developed a way of working to make this huge project of a world history of design manageable.

—Victor Margolin

Notice here that Victor Margolin doesn't indicate that it was a process that he was taught, but rather "I've developed". Of course he was likely taught or influenced on the method, particularly as a historian, and that what he really means to communicate is that this is how he's evolved that process.

I begin with a large amount of information.

—Victor Margolin

As I begin to write a story begins to emerge because, in fact, I've already rehearsed this story in several different ways by getting the information for the cards, mapping it out and of course the writing is then the third way of telling the story the one that will ultimately result in the finished chapters.

—Victor Margolin

website | digital slipbox 🗃️🖋️

No piece of information is superior to any other. Power lies in having them all on file and then finding the connections. There are always connections; you have only to want to find them. —Umberto Eco

Howdy, Stranger!

Comments

I believe Victor Margolin when he says that he developed his own system. That's what I did in the years before people started widely discussing personal knowledge systems online. Nobody taught me how to do it when I was in college. @chrisaldrich repeatedly tries to connect everyone's knowledge practices to an ongoing tradition that stretches back to commonplace books, but he overstates it. There is such a thing as independent development of a personal knowledge system. I know it because I've lived it. It's not so difficult that it requires extraordinary genius.

Re: @chrisaldrich repeatedly tries to connect everyone's knowledge practices to an ongoing tradition that stretches back to commonplace books, but he overstates it.

Howdy Andy, nice to meet you.

Hmm... Let us agree to disagree. Certainly there was (is now too) a tradition, in academia of categorizing notes in exactly these types of ways, witness this link:

Certainly there was (is now too) a tradition, in academia of categorizing notes in exactly these types of ways, witness this link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zettelkasten#History

Chris in my mind has simply documented the obvious...

Tinybase: plain text database for BSD, Linux, Windows (& hopefully Mac soon)

@Andy I don't think that the history @chrisaldrich is presenting is not so much about an actual causal chain but about collecting more and more of the historical events and entities to paint a big picture. From my experience in academia, it would be quite a miracle if you got into a position and not observe peers how they do it, ask professors when you are student how they manage their stuff, learn from role models etc.

I think that making the hypothesis that each method is in part learned or inspired by a tradition, so actually making the case for a causal chain, is even stronger than the hypothesis that true independent invention was happen regularly.

I am a Zettler

@Sacha @Mike_Sanders What I oppose is the attitude of @chrisaldrich that he knows better than everyone else, that he's better than Vannevar Bush (who according to Chris did "a massive disservice to the computing field"—no, I think not) or Victor Margolin (of whom Chris presumes to tell us "what he really means to communicate"—no, I think Margolin is right to say what he says and knows well enough what he's doing) and that everyone is really just making commonplace books like 500 years ago, with a few tweaks. No, there is a lot more interesting variety and complexity than that.

A brilliant video, full of insights and easy to understand. And it is based on a clear and simple structure. - Thank you for sharing.

Here is my structured note from "analytical watching" [1]:

References:

[1] Adler, Mortimer Jerome, and Charles Lincoln Van Doren. How to Read a Book. Touchstone edition. New York, Touchstone, 2014.

Edmund Gröpl

100% organic thinking. Less than 5% AI-generated ideas.

I tend to agree. I see, in that, something similar to "convergent evolution" in the Theory of Evolution.

Similar needs (same pressure) bring to similar solutions (similar adaptations).

Zettelkasten basic principles are simple in the end, so it's not a surprise that they may have found independent development in several places

It's also probable, anyway, that some of the authors have met not a whole "ancestor method" but some "common seeds" in their life before developing their method. They often have in common a lot of schooling and education, reading and studying same books. Much less randomness is involved.

I agree, the similarity to "convergent evolution" is accurate. Zettelkasten has simple principles that could easily have been discovered independently. Common educational experiences of many authors can lead to similar methods, further supporting this theory.

It's worth noting that such an approach might have been inspired by similar readings or teachings. It's interesting how these "common seeds" influence the development of various note-taking methods.

Greetings, Andrew https://mazzani.pl/projektant-wnetrz-cennik-warszawa/